All cannabis varieties are named. Where did these names originate, and what do they signify to consumers today?

Since the early 20th century, cannabis has been smuggled into the hands of Western consumers. Little, if any, marijuana was grown in Europe and North America until the 1960s, and domestically grown “sinsemilla” flowers first appeared in the 1970s.

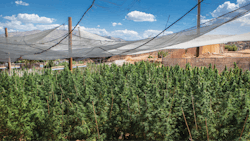

The names and identities of smuggled marijuana varieties were derived from their regions of origin. Smugglers had their own secretive ways, but their products’ names indicated closely where the shipments originated. Smokers commonly knew that the “weed” they were smoking came from either Colombia, Jamaica, Mexico, Thailand or another exotic location. Consuming something from an exotic land adds a sense of association with the region, as well as the culture and people who produced it. Smokers’ curiosity as to the origins of their weed even spurred some to travel widely and learn more about the world around them. Their pursuit of cannabis brought Westerners face-to-face with cultures whose impact on Western society still resonates today.

Smuggled marijuana often contained many seeds, sometimes way too many, but those annoying parcels of unique genetics were occasionally put to good use in home gardens. Sinsemilla varieties home-grown each year from seed were also named after their host communities—from Gainesville Green to Big Sur Holy Weed to Maui Wowie.

The imported flowers’ colors were also important in the descriptive branding of the era. Names such as Acapulco Gold and Panama Red from the late 1960s and early 1970s are still associated with marijuana today and provided imported marijuana with what were essentially the first cannabis brand names. Independent entrepreneur outlaws provided the product, while rock ‘n’ roll music provided the advertising:

“We’re goin’ south To get that Acapulco gold Ain’t nothin’ it can’t fix Old dogs can learn new tricks When the streets are lined with bricks Of Acapulco gold.” - from “That Acapulco Gold” by The Rainy Daze — 1967

“Panama Red, Panama Red He’ll steal your woman, then he’ll rob your head.” - from “Panama Red” by the New Riders of the Purple Sage — 1973

The relationship between music and cannabis varieties would reemerge years later with hip-hop acts such as Cypress Hill, whose close ties to the cannabis underworld became trademarks of their branded identities.

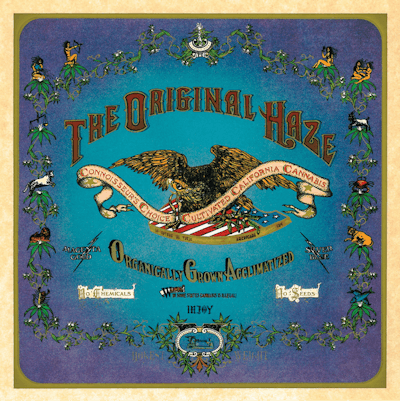

The names of now-classic varieties such as “Purple Haze” were drawn from the music of the times, or, as is the case with “Skunk,” from their characteristic varietal aromas. Early indoor-grown clonal varieties were granted personal code names. These names were first used by the initial growers as a means of identifying a single plant and its seed offspring or its clone line, and by consumers to denote favored types of sinsemilla. More recently, with increasing market interest these “pet names” have evolved into the brand names widely used for cannabis as well as other popular products. The market is filled with hundreds of supposedly unique varieties, but genomic analyses from groups such as Phylos Bioscience and Medicinal Genomics reveal that many are identical, and they are actually a group of clone-only cultivars taken directly from the same earlier varieties. Consumers feel they are trying something new, but only the names have changed. In addition, lesser varieties were often given these famous names to increase their salability.

Clonal cultivars such as “OG Kush,” “Sour Diesel” and “Blue Dream” have become brands themselves, and any company that acquired these cultivars early on had an instantly recognizable and easily marketable product. Eventually, many growers acquired these once rare, but now ubiquitous cuttings of top-shelf genetics and ended up having the same flowers as their competition.

Today’s Realities

By now, it is becoming clear that the age of the cultivar name also serving as the brand name is reaching its end. The new market, which often requires cannabis to be sold as a packaged product, forces the customer to make purchasing decisions based on brand loyalty. Company names are becoming more important than the names of the varieties they sell.

In the adult-use cannabis market, the flower aroma and taste profiles are of paramount importance in determining customer preferences. Unique cannabis flavors result largely from the presence of varying amounts of aromatic terpene compounds. Modern, strong-smelling (“loud”) indoor varieties are often named after their flavors and aromas (i.e., Pineapple Express, Strawberry Cough and Lemon Haze). A recent trend has been linking sinsemilla flavor profiles with popular dessert items: Variety names such as Cherry Limeade, Gelato, Zkittlez and GSC (formerly known as Girl Scout Cookies) reveal our underlying desire to consume sweet products. Naïve attempts to name cultivars after pre-existing brands from other markets has brought numerous lawsuits against cannabis companies, resulting in the changing of cultivar and company names so they do not infringe upon previously existing brands (i.e., GG Strains’ GG4, formerly Gorilla Glue #4).

In fact, terpenes do not make sinsemilla taste sweet. Aromatic compounds trigger associations with previously experienced sweet products. This association also guides the breeding and selection of modern cultivars. Like an ice cream company, many flavors are available, but, essentially, all ice cream is frozen milk and sugar. But in contrast to dessert items, the terpenes that make up these new aromas also modulate the cannabis’s medicinal and other effects.

Each cannabinoid accounts for its own range of effects in each individual user. But the limited number of known cannabinoids (i.e., CBD, THC and a handful of others) cannot account for the astonishing complexity of the cannabis “high,” and as we steadily gain more information, it is becoming clear that the terpene compounds (commonly more than 50 in each variety) are the modulators of cannabinoid effects, providing the wide range of efficacy experienced by cannabis consumers.

When companies select sinsemilla cultivars for the commercial market based solely on their aromatic terpene flavor profiles, they are dictating the range of associated effects for the end users, often without considering what the desired outcome for a given consumer group may be. Future branding will increasingly describe physical and mental effects of varieties represented by their characteristic flavor profiles. Understanding the relationships between effects, flavors and fragrances, and their influences on plant variety selection and marketing, will be vital to success in the normalized cannabis world.

Serving Different Needs

Typical cannabis users of the past do not readily fit into the present-day customer model, and there are a great many cannabis users who struggle to identify with the brands available today. With the exception of edibles, topicals and, to a lesser extent, vape pens—which are all relatively new product forms—we perceive that today’s sinsemilla consumers still pay more attention to the varietal name “brand” than the brand name on the package and that they choose products whose attributes best suit their individual needs and tastes. As consumers begin to identify with brands, it will become more critical to pair cultivars and brand names with a particular user group. Cannabis use crosses many cultural, age and regional boundaries. This creates numerous opportunities to market one’s brand to a consumer group.

Star appeal was an early attempt at sinsemilla branding. The Marleys, Snoop Dogg, Tommy Chong, Willie Nelson and Whoopi Goldberg all had their early releases. In the future, “star appeal” is more likely to emanate from a well-known persona within the cannabis industry. This has become a branding model for numerous luxury products such as wine, perfume and clothing with brand names like Mondavi, Chanel and Armani that convey quality through the celebrity status of the name attached to the brand.

Creating narrative (the explanation of a cultivar’s heritage and provenance) is an important element in cannabis branding. More and more, clandestine growers are emerging to publish versions of their origin stories, and stake their claims to a piece of the economic pie. The “immaculate conception” notion of ushering cannabis varieties into the rapidly normalizing system suppresses consumer awareness of heritage and disconnects the cultivars from their narratives, which are crucial to today’s branding of cannabis varieties.

With most agricultural commodities, the consumer chooses named varieties of fruits and vegetables available from numerous production regions. But cannabis plants find their way into new jurisdictions through clandestine channels, and during this process the names are often changed to either obfuscate their origins or to create market appeal by claiming to be unique, new varieties. This makes it additionally challenging for companies to establish their own brands and creates confusion for the consumer. Companies continue to fight over their rights to use these varietal brand names.

What Tomorrow Brings

Future cannabis branding will take into account many aspects of our present and historic relationships with cannabis that determine how and why we make purchasing decisions. As prohibition takes its last dying gasps, many who remember its impact still associate cannabis with decades of severely destructive drug wars. As new consumers begin to purchase cannabis products in a fully regulated and legal market, motivations for them to choose one product over another will likely be influenced by the same market forces that dictate their purchases of other legal luxury products. The first and foremost consideration is cost, supported by a quality assessment.

With an international cannabis market establishing itself, it is quite possible that in the near future we may be purchasing cannabis from far-off exotic lands, in much the same fashion that we did decades ago. Only this time, consumers may be offered fair trade, organically produced, exemplary flowers produced in regions where the terroir will perfectly complement the cultivars farmers choose to grow.

As society reincorporates cannabis into a normalized distribution system, we can evaluate with a fresh perspective what it is we want from our cannabis brands. Many cannabis consumers now prefer products that are grown on organic rather than conventional farms, are locally produced rather than imported, and of boutique origin instead of industrial production. We are setting out on a positive path toward functionally characterized cannabis products promoted by highly creative and effective branding. It will be exciting to follow our industry’s progress.