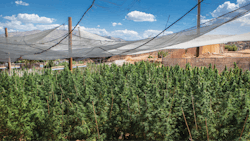

Cannabis crops growing under naturally irrigated and fertile conditions thrive in direct sunshine as they have for millennia. The selective pressures of marijuana prohibition increasingly forced illicit growers to look for closets, attics, basements and bedrooms in which to grow their crops, while their prolonged trial and error eventually made it feasible to produce high yields of very potent sinsemilla flowers in artificial environments. Many now-legal growers still follow the prohibition manuscript and continue to expand their indoor grows into ever-larger warehouses and dedicated indoor grow facilities that rely on supplemental lighting and an array of other specialized equipment.

Indoor cultivation has allowed for the mass expansion and present-day diversity of the cannabis industry, providing a myriad of safe and productive growing environments. These environments have supported a plethora of modern sinsemilla varieties that have been multiplied and widely distributed by growers and breeders worldwide. Along with the possibility of harvesting multiple crops each year, indoor growing brought the joys of sinsemilla horticulture to virtually every corner of the globe and made production of high-quality cannabis available to every potential enthusiast.

Indoor growing conditions also engendered the preservation of the countless cultivars available today. Cannabis is an annual plant, which survives as seeds during the long, cold winter months, to sprout again in the spring, and complete its life cycle by autumn. Growers generally lack true-breeding seed stock, and without the now-widespread ability to create and control indoor growing conditions, many cannabis varieties would have been irretrievably lost. Many clonal varieties we enjoy would not be available today had we been unable to protect and overwinter vegetative cuttings in indoor grow rooms. However, many modern varieties were selected specifically for indoor production, do not perform well outside and, without the electric grid, would not be favored by growers.

Indoor Cannabis and Its Ripple Effect

Indoor growing is costly, however, and because of that, combined with prohibition pressures, high-quality indoor sinsemilla flowers have always been an overly expensive agricultural product. Illicit indoor sinsemilla growers, who were most often limited by high production costs and relatively small facility sizes, were forced to charge their customers a premium for the lingering threat of arrest during prohibition. But, as long as prohibition ensured less sinsemilla was being produced than consumers wanted to buy, demand exceeded supply, the retail price remained high and the electric bills were reliably paid.

Indoor growing started simply as a successful way to hide crops from cops, and today’s indoor growing is largely a residual effect of vigorous prohibition; but sinsemilla growing is already legal (or de facto legal) in many jurisdictions nationwide. While growers’ risks are increasingly minimized, marijuana supplies have reached all-time highs in many markets, and prices have reached all-time lows. In addition, sinsemilla flowers are becoming raw material rather than only end products, and extracts and isolates are now flooding the cannabis market.

Cannabis crops growing under natural sunlight might require supplemental soil nutrients and sufficient water, but few, if any, additional inputs. Creating paradise indoors is costly in several ways. In addition to expensive infrastructure, modern-day sinsemilla crops grown in artificial grow facilities require commercial lighting, heating, air conditioning, dehumidification, fans and carbon dioxide supplementation, which all rely on fossil fuels. Prohibition transformed cannabis from a sun-grown crop, cultivated by traditional farming techniques with a minimal carbon footprint, into a significant environmental concern.

A minority of growers are blessed with living in climates favorable to greenhouse and outdoor growing, and the remainder still make do by practicing their tried-and-true indoor-production strategies. Following the lead of every other major agricultural crop, cannabis production is slowly shifting to locations where it is economically best suited—with some agriculture companies favoring greenhouses and broad-acre fields in regions with abundant water, sunshine and low labor costs. We envision that much of production will return to regions worldwide where cannabis has been grown successfully for centuries.

Tomato Trends

Our consulting company, BioAgronomics Group Consultants, serves the domestic and international cannabis industries, and we often advise our clients based on our predictions for the international future of cannabis production and sales. It is always valuable to compare our nascent cannabis industry with more mature, yet actively evolving agribusinesses, and our studies offer insights into the possible future of the cannabis industry. Let us take a look at some telling trends in the modern tomato industry.

Internationally, the largest greenhouse vegetable industry, by far, is tomatoes. (Tomatoes are actually fruits because they contain seeds, but they are legislated as vegetables.) Although North America provides the largest market for tomatoes, China, India, the United States and Turkey lead world tomato production. Greenhouse tomato growing increases annually in all these regions, with the Dutch and Belgians leading the industry in both efficiency and yield per hectare.

Presently, greenhouses account for only about 30 percent of world tomato production, while the remainder is still grown outdoors. While field production accounts for some of the fresh-produce trade, outdoor-grown tomatoes are largely destined for processing.

Greenhouses offer tomato growers potential harvests spanning up to eight months of the year, and with heating and supplemental lights, economically lucrative production (amortized over the whole year) is achievable year-round. Greenhouse production of all crops in climates with cold winters is subject to a winter period of lower yields, lower consumer-quality ratings and much higher energy costs to provide off-season heating and supplemental lighting. Commercial outdoor and garden tomatoes are seasonal, and we enjoy them when we can—otherwise we must eat what agribusiness makes available year-round.

The balance between production costs and profits drives the agronomic realities of tomato and other greenhouse crop production, including cannabis.

Production of cannabis is also most consistently achieved indoors and in greenhouses, but production costs must be supported by consumer preference for the highest-quality, indoor-grown flowers. Surely one can pay a premium to buy an organically grown, sun-ripened tomato year-round, yet greenhouse tomatoes dominate the fresh market for economic reasons. Prohibition raised the price of cannabis products far beyond the effects of simple agronomic factors, and as the outdated prohibition model sails into the sunset, agronomic factors will become the most important determinants of the cannabis industry’s evolution.

In today’s world of agribusiness, profitable greenhouse tomato production is reliant on artificial lighting, automation and additional technologies. While greenhouse production also relies on fertilizers—non-organic outdoor production does as well. Tomato crops grown in both greenhouse and outdoor environments are increasingly irrigated, fertilized and packed by automated production lines that are extremely expensive to install. Outdoor farms also are able to utilize automated picking machines. Large companies pay for their initial expenditures on automation, as they see significant labor savings at such scale. This is the way forward for commoditized agricultural industries.

In addition to the many similarities, distinct differences also exist between the tomato and cannabis industries. For instance, tomatoes are only rarely commercially produced in indoor grow rooms, yet there are several important comparisons that can be highlighted. Cannabis flowers and their products do not feed the fresh-food market—they are not sold to the salad industry as fresh tomatoes are. The cannabis dried-flower market, as well as the extracts and concentrates markets, are more analogous to the processed tomato market for ketchup, paste and soup than they are to the fresh-tomato market. And, the extended shelf life of cannabis products lends itself to international commodification.

Worldwide commodification already creates challenges for another cannabis industry: hemp grain seed crops destined for food and oil production. During the past two decades, Canada emerged as the world leader in comestible hemp seed production, largely because hemp production remains federally illegal in the United States—the largest market for Canadian seed. In an increasingly commodified world, China has also become a major exporter of hemp seed, and China delivers hemp seed worldwide at wholesale prices well below Canadian farm gate prices (price for sale direct from the farm/producer). Countries such as Australia and New Zealand, with smaller economies of scale than Canada, have even higher farm gate prices for their seed and are even less competitive in the world marketplace. Trends in the hemp seed market continue to change as the industry matures and finds regions with the lowest costs of production.

Agronomics and Economics

Legislation, whether it is environmentally motivated or not, is of much lower impact on agricultural production than agronomic factors. Cannabis legalization results in higher production costs, largely through regulatory compliance and taxation. Commodified agro-industries react to increased production costs by steadily moving to regions of lower legislative, labor and agricultural input costs. As we head toward an internationally commodified cannabis economy, how can cannabis flowers grown indoors in Ohio or in a California greenhouse with supplementary light and heat, compete with field-grown cannabis from warm latitudes with year-round outdoor flowering light cycles (e.g., Colombia and Mexico), where labor costs are low and the only electrical input required is to power strings of low-wattage bulbs for only a few hours each night?

Today, greenhouse-grown flowers sell for less than indoor-grown flowers, and sun-grown outdoor flowers sell for even lower prices. As availability increases, wholesale prices will certainly continue to drop. One may argue that indoor flowers are often higher quality than outdoor flowers, but will future consumers pay extra for this distinction? Will indoor cannabis farmers find niche markets where their more-expensive products will be appreciated?

Clearly, we would not have been catapulted into the modern cannabis age without the benefits of artificial growing environments. But now we must collectively determine the best path forward for modern cannabis agriculture while reducing our collective carbon footprint. Improved technology is already coming to bear fruit. Growers are experimenting with more environmentally friendly techniques, lighting companies continue to develop more efficient lighting and fertilizer companies are working on nutrient recycling. Access to renewable energy is another highly significant aspect affecting the carbon-footprint debate, in part determining whether indoor cultivation facilities will find their place in a more environmentally sustainable future. Clean, renewable energy sources could allow for the proliferation of indoor cultivation, especially into additional regions of the world lacking ideal growing conditions, since indoor facilities may be set up at virtually any location on the globe with access to electricity.

The cannabis industry in its current incarnation is enjoying a time of expansion, an innovative developmental phase fueled by hopeful investment and moderated by careful thought, yet regrettably tied to outdated prohibition-era thinking, And it remains subject to the inescapable laws of agronomics. As present-day, small-scale production models are overgrown by post-prohibition agribusiness, the industry must continue to service and encourage existing methods for environmentally sustainable cultivation, while identifying and creating future markets for their sustainable technologies.

Right now, there appears to be endless room for expansion in the new cannabis-agriculture sector. As an increasing number of regions adopt progressive cannabis regulations, they will look to those who have already embraced the process in order to weigh the advantages and disadvantages of each system, and to decide which rules and regulations make the most sense for their individual conditions. Production, distribution and pricing are still determined by the mosaic of regional strategies based on wide variations in the legal status of cannabis. Federal legalization is inevitable, and future cannabis farmers in each region will clearly become savvy as to which methods and equipment are essential to produce the best possible crop at the lowest possible cost.