Presently, only a handful of jurisdictions differentiate between medical and adult-use by imposing lower taxes on medical cannabis companies and their sales. Because most jurisdictions profit equally from their production and sale, our analysis explores only taxation policies for adult-use cannabis.

State, county and city government officials across North America see cannabis taxation as a lucrative revenue source, yet exorbitant taxation is already suffocating the cannabis industry in its infancy. Presently, U.S. cannabis taxation is a complex patchwork requiring considerable effort to comprehend. Depending on the jurisdiction, approaches to taxation vary widely in both how, where and at what rate taxes are extracted along the supply chain from plant to product, creating a highly diverse set of outcomes.

Federal cannabis taxation policies are yet to be designed, approved and implemented. Alcohol and tobacco products are already federally taxed, and we have much to learn from their examples. Now is the time for our industry to weigh various options and make unified suggestions to policy makers.

In Part I of this Growing Pains series on cannabis taxation, we will explore the present-day convoluted landscape of U.S. state and local taxation extremes and inconsistencies while searching for taxation systems that may prove germane to future policy decisions. Part II will present the possible advantages of creating a federal cannabis tax based on potency, with highlighted parallels to current taxation of alcoholic beverages and tobacco.

Federal Excise Taxes on Alcohol and Tobacco

Excise taxes are indirect taxes established by many countries’ federal, state and local governments on goods and services such as alcohol, tobacco and cannabis products, which may be levied simultaneously by multiple jurisdictions. Most excise taxes are collected from producers and/or retailers rather than being paid directly by consumers and are concealed in the retail price of the product.

The U.S. federal government is no stranger to excise taxes from which it derives a lucrative source of income. Alcohol and tobacco excise taxes are collected by the U.S. Treasury Department’s special Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau. According to the Tax Policy Center, in 2019, the U.S. highway system generated more than 40% of excise tax income, followed by aviation at 16% , tobacco at 13% and alcohol at 10%, with a wide range of taxable sources accounting for the remaining 16%. With alcohol and tobacco already accounting for nearly one-quarter of excise tax revenue, the federal government harbors high expectations for additional cannabis taxation.

U.S. federal alcohol excise taxes are levied on distilled spirits, wine and beer based on their content of the active ingredient ethanol. (In Canada, distilled spirits, wine and beer are also taxed based on ethanol content.) In the U.S., spirits are generally taxed $13.50 per proof gallon (50% ethanol), adjusted to the actual ethanol content. Wine taxes are $1.07 per gallon for wine containing less than 16% ethanol and $3.40 per gallon for sparkling wines, while beer is taxed $18 per 31-gallon barrel. It is noteworthy that smaller volume brewers are taxed only $3.50 per barrel on the first 60,000 barrels sold. This tax break has proven important during the early establishment of the localized craft beer industry, allowing this nascent industry an initial advantage over the major national brewers. Revenue from alcohol tax in the U.S. amounted to $10.27 billion in 2021.

Excise taxes imposed on all tobacco products sold in the U.S. are calculated per 1,000 cigarettes/cigars or per pound of tobacco and are collected when products leave bonded facilities for distribution, but these hidden taxes are also passed on to retail sales. Note that tobacco taxes are based on product count or weight, not on the amount of the active ingredient nicotine or other compounds. Taxes on products ranging from cigarettes to roll-your-own tobacco generated $12.4 billion in 2021. Once again, Canada follows a similar system, taxing cigarettes by the pack and bulk tobacco per 50 grams.

U.S. and Canadian Cannabis Taxation

In both the U.S. and Canada, federal potency-based taxes on alcoholic beverages are levied on the ethanol content—higher potency equals higher taxes. However, U.S. state and local cannabis taxation has followed examples from both alcohol and tobacco taxation, which has created a confusing hodge-podge of systems across the country.

Canada serves as our closest example of federal cannabis taxation. Canada imposes a cannabis excise tax of $1 per gram of flower, or roughly 10% of the retail value of the average sales price when the market launched. Provincial cannabis taxes on sinsemilla are about three times higher than the comparable U.S. state taxes.

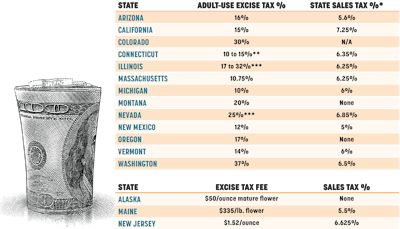

Cannabis taxes for adult-use programs were first collected in Colorado in 2014, followed by: Washington in 2015; Oregon in 2016; Alaska in 2017; California, Nevada and Maine in 2018; Massachusetts in 2019; Illinois and Michigan in 2020; and Arizona in 2021. Montana, Connecticut and New York approved adult-use cannabis sales but are yet to collect taxes, bringing the total number of cannabis-taxing states to fourteen. Taxation most commonly began with medical cannabis followed by adult-use.

Most states with adult-use programs add excise tax either at the wholesale level, including Colorado 15%, Nevada 15%, Illinois 7% and/or at the retail level, such as California 15%, Nevada, 10%, Massachusetts 10.75%, Michigan 10%, Colorado 15%, Arizona 16%, Oregon 17%, New Mexico 12%, Illinois 10 to 25%, and Washington 37% (see chart above). State sales taxes generally apply, too.

Most establish cannabis taxes on a percentage basis at the wholesale level and also add retail sales taxes of 6% to 10%. The full tax burden on cannabis consumers in adult-use markets varies widely, for example: New Mexico 17%, Michigan 16%, Massachusetts 17%, Oregon 17%, Arizona 21.6%, Vermont 20%, Montana 20% Colorado 30%, Nevada 31.85%, Illinois 23.25% to 44.25%, and Washington 43.5%. In some jurisdictions, local county and city surcharges may also be added that are not included here and additionally increase the consumer price.

Three states impose excise taxes based on product type and weight. Licensed cultivators in Maine pay a $335 excise tax per pound of flower, $94 per pound of trim, $1.50 per immature plant and $0.30 per seed. New Jersey increased its excise tax fee to $1.52 per ounce in 2023. Alaska charges a whopping $50 surcharge per ounce of mature flower, $25 per ounce for immature flower, as well as $1 per cutting.

Excise taxes based on a percentage of the wholesale and/or retail price allow for price fluctuations, while flat taxation rates based on weight do not accommodate changes in price structure. A $20 dollar tax on a $200 ounce is a 10% tax, but a $20 tax on a $20 ounce represents a 100% tax.

As wholesale sinsemilla prices plummeted in California, Colorado, Oregon, Michigan, Massachusetts and elsewhere, tax rates stayed the same. When taxation schemes were established, wholesale sinsemilla prices ranged from $2,000 to $4,000 per pound (depending on whether grown indoors or outdoors) and now range from $300 to $1,500 per pound, although prices vary widely and fluctuate from state to state. Flat-fee excise taxes were suddenly many times higher compared to the wholesale value of the flowers. New Jersey, Maine and Alaska charge flat excise taxes on cannabis flowers, and stakeholders all along the supply chain from growers to consumers suffer the consequences. Although California recently moved to a percentage tax instead of a weight-based fee, moving the liability from growers to retailers, consumers will still pay these taxes, and prices must account for this.

Cannabis policies, regulations and tax structures were developed and implemented from the state level down, allowing independent cannabis policy decisions to be made by counties and communities acting autonomously, which resulted in a patchwork of local approaches to taxation. Such discrepancies must be considered and corrected when establishing a reasonable federal cannabis taxation policy.

Combined state adult-use cannabis tax revenues collected since 2014 have reached $15 billion, according to the Marijuana Policy Project. Yet exorbitant taxes are strangling the golden tax goose.

California Case Study

California is by far the largest sinsemilla producer and serves as the prime example of variable tax rates. According to the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration, the state’s 2021 tobacco tax revenues yielded almost $2 billion, and alcohol tax earnings exceeded $428 million. In 2022, the cannabis industry accounted for more than $1 billion in tax revenues.

Taxation levels vary widely throughout California, with urban areas on average taxed more than rural. According to a 2021 Leafly survey, Los Angeles, Oakland and San Jose were the most expensive cities, each charging an additional 10% tax on gross receipts from cannabis sales.

In addition to the state tax, some California counties also impose taxation systems and rates ranging from taxing the growers’ gross sales receipts, imposing square area charges for crop canopy or facility size, collecting flat taxes per weight of dried flowers, charging annual flat rate fees on non-growing operations, and/or adding individual cannabis business taxes. Calaveras County charges the highest combined cannabis tax rates at $2 to $5 per square foot of canopy, plus $45 to $70 per pound levied on the growers, plus a 7% manufacturing tax, plus a 7% storefront tax.

Each single tax may seem reasonable, but a single gram of sinsemilla passes through several taxable levels along the supply chain from growers through manufacturers, distributors and retailers before reaching consumers, and processed cannabis products can pass through even more hands. The tax paid at each step is passed on and included in the retail price, and again consumers bear the tax burden in their purchase.

Not all California counties charge cannabis taxes, but their cities may. Thirty cities in 17 counties that do not impose cannabis taxes impose their own taxation systems and rates. Also, 20 cities in seven of the cannabis-taxing counties levy cannabis taxes in addition to state and county taxes.

Cities also tax cannabis businesses at several levels, but generally less so on the flowers and products themselves, resulting in high “footprint” taxes but fewer flower taxes or flat-rate tariffs. Like the counties, city taxes are also collected at many positions along the supply chain, including the following: taxing the gross proceeds/revenue of growers, manufacturers, distributors, transport and testing facilities; square area charges based on canopy or facility size; cannabis business license or permit taxes; personal cultivation surcharges; transportation taxes and/or point-of-sale taxes.

Civic approaches to cannabis taxation vary widely, and city strategies for extracting taxes can be even more diverse and extensive than county strategies. Berkeley and Oakland in Alameda County levy some of the state’s highest taxes, while San Francisco just across the Bay Bridge has suspended cannabis taxes altogether.

We will take as a case-in-point cannabis taxes in Alameda County and their effects on retail pricing. Unincorporated areas of Alameda County do not impose cannabis taxes, but the larger urban centers do. Alameda’s Oakland city tax is 10%, while the Berkeley city tax has been reduced to 5%. Add on top of this a 10.25% over-the-counter sales tax (7.25% California state sales tax plus a 3% Berkeley city sales tax ).

The price of an eighth of an ounce (3.5 grams) of mid-range sinsemilla selling for $40 will include $1.15 in state cannabis taxes and approximately $5 in manufacturing and distribution taxes, adding around $6.15 to the retail price, plus $1.75 in city cannabis taxes and $3.50 in combined sales taxes, making what would be without taxes a less-than-$30 eighth have a final retail sale price of around $40. In Los Angeles, Oakland and San Jose, the price would rise to $42.

When California consumers purchase cannabis products in cities within tax-levying counties, then they are taxed four times over—state tax plus county taxes plus city taxes plus sales tax. Consumers in other states are experiencing similar tax burdens. Can the already faltering cannabis industry withstand an over-riding fifth federal tax? State cannabis taxation systems as they exist now are costing the cannabis industry and consumers much more than seems practical. How might the federal cannabis taxation system be structured to benefit both our industry and our country? We’ll explore this question in Part II.