Far up a remote river, deep in the Amazon rain forest, a local plant hunter stands on a rickety dock in the smoky haze, wearing clothes tattered from days of navigating the thick jungle. In his outstretched hand, he clutches a soiled canvas bag. A few protruding leaves peek hopefully at the early morning sun. He waves to the oncoming boat to come ashore. On board is a world-renowned ethnobotanist, traveling the globe on behalf of a pharmaceutical company, in search of rare indigenous plants with traditional medicinal uses.

Upon their transport overseas, these exotic plants will become established in a foreign land, and will be assayed for rare compounds that may ultimately be turned into valuable medicines.

Numerous advances in modern medicine have been achieved since science has gained a better understanding of traditional plant uses. Many of today’s most successful prescription medications were discovered by exploring the relationships between peoples and plants—and yet, only a small percentage of plants have been investigated for their medical efficacy by modern science. Prospecting for plants that produce natural compounds that can be clinically shown to fight diseases, then patenting these compounds (naturally sourced or preferably synthesized) and finally capitalizing on their sale for great profits, is the key strategy driving the international “Big Pharma” industry.

The modern cannabis industry is experiencing a similar situation with the transfer of varieties to large, corporate cannabis interests. The crowd-sourced selection and breeding of modern cannabis varieties—and their widespread dissemination—offer much easier opportunities for the cannabis corporations of the future to acquire promising varieties. From the seed collectors of the hippie trail (a movement of Westerners, from the 1960s through the 1970s, along a route from Europe to South Asia that passed through many of the world’s premier hashish-producing hubs), to the innovative Dutch seed companies, and eventually the California dispensaries—the cannabis subculture has delivered the results of its great collective effort, risk and expense right to corporations’ doorsteps. However, while drug varieties of cannabis have become widely available, Big Pharma’s ability to utilize those plants in a pharmaceutical application is certainly not simple.

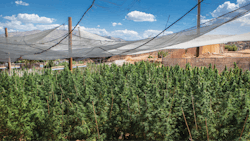

The Agribusiness of Cannabis

Emerging international cannabis agribusinesses are beginning to realize that cannabis is one of our most complex plant allies. Cannabis is genetically diverse and provides us with a kaleidoscope of possibilities in terms of choosing appropriate cultivars for specific purposes. Not only do varieties differ in agronomic characteristics such as size, yield and potency, but cannabis plants’ chemical contents are also quite complex. Cannabis-derived medicines and other products are characterized by the content of specific secondary metabolites (such as cannabinoids and terpenes) and are extracted from specialized cultivars that produce high levels of these target compounds. In a parallel way, industrial hemp cultivars are characterized by their fiber and seed yields, but additionally by their fiber qualities, essential fatty acid profiles, protein contents and other agronomically valuable traits. Recently, the CBD contents of industrial hemp cultivars became of great interest, and the multi-use medicinal-industrial hemp industry was born.

Cannabis produces many cannabinoids, terpenes and other active compounds that in various combinations offer myriad therapeutic properties, and many may prove effective for the relief of a wide range of common medical conditions. This is a strong reason for using whole flowers with the highest possible chemical complexity and diversity, rather than concentrates and extracts that contain fewer potentially beneficial compounds. This situation also emphasizes our need to determine which compounds and combinations are the most effective and desirable, and eventually how to provide them in the most economical way. To move forward as an agricultural industry, we must rely on collaborative efforts between businesses (and their interests) and growers of excellent cannabis, as well as those with access to rare and valuable cultivars.

In the medicinal cannabis industry, a cultivar’s chemotype or chemical profile is of critical importance. Patients must receive the same suite of active compounds in the same proportions and amounts each time they buy their medicines. The present-day agricultural strategy of asexual clonal reproduction of identical cuttings grown under controlled environmental conditions offers us this required consistency on a grand scale.

Science continues to prove the efficacy of THC and CBD. As we continue to study the human-cannabis relationship, we will realize additional uses for cannabinoids, terpenes and other compounds. Sourcing these compounds from the appropriate cultivars will be an exercise in discovery that may eventually lead to large multinational companies seeking valuable plants from all corners of the globe, but their initial bioprospecting has already begun much closer to home, collecting cuttings of commercially available clones.

Herein lies the challenge for Big Pharma (and many other purveyors of cannabis): Once companies decide which varieties will provide them the appropriate compounds for their products and formulations, they must source plant stock from the cannabis ecosystem at large. Recently, variety sourcing has become cloaked in mystery, and the origins of plant acquisitions have been conveniently left out of the record books. This was, and in many regions still is, “the immaculate conception era” when valuable plant material continues its silent spread worldwide to magically reappear under another identity. In other crops such as wine grapes, highly respected cultivars were acquired in Europe surreptitiously and smuggled over borders against agricultural sanctions to establish emerging New World wine regions from North America to Chile. With no mechanism to authenticate varietal identity, individual plants were easily shuffled into the young vineyard systems, where they have been perpetuated asexually as grafted clones ever since.

As agricultural markets mature and commodify, certain varieties come to dominate production. There may be as many as 8,111 individual wine grape varieties worldwide, according to the International Organization of Vine and Wine. Presently, the U.S. is home to several hundred, but Chardonnay and Cabernet Sauvignon together account for more than a quarter of wine grape acreage, and the top eight varieties account for more than half of production. Growing regions also become more focused; around 90 percent of U.S. wines are produced in California.

Seeds to Dollars

Now that cannabis is quickly becoming an international commodity, the needs to define the agronomic traits of specific cultivars, and to make those cultivars available worldwide, are more pressing than ever. Just as cultivators and manufacturers are beginning to decipher what agronomically valuable traits they desire from their production plants, crowd-sourcing is becoming less reliable, and there is an urgent need for the provision of genetically reliable and pest-free nursery stock.

Increased reports of blight levels of mites, mildews, molds, viruses and, most recently, “dudders disease” are of great agronomic concern. Development of clean stock practices and a certified supply chain of production-ready plantlets, along with selection and breeding of locally adapted cultivars resistant to infestation by the most troublesome cannabis pests, are the two most important goals upon which the economic future of our international cannabis industry rests.

It is difficult to calculate accurately what the value of any cultivar may be over time. Yet we may speculate that since cannabis is already a multibillion-dollar crop in North America, in the relatively near future, it is likely that far fewer cultivars will be widely grown, but that each surviving cultivar could create hundreds of millions and possibly billions of dollars of revenue in its agricultural lifetime. The opportunities are tremendous.So, where are these billion-dollar plants now, and who will control them in the future? They could be almost anywhere—flowering in the garage next door, thriving in the Himalaya Mountains of Nepal or hidden in the seeds you are yet to sprout. The first waves of cannabis bioprospectors collected seeds under the most trying conditions. The most favorable plants that survived from this early experimentation were preserved at great personal expense and potential risk of incarceration, and they were protected by their shepherds and custodians who recognized their unique values to society. Today, many of these traditional heritage sinsemilla varieties are becoming the agronomic equivalent of heirloom apple varieties: delicious and sentimental to enjoy, but not the bulk of the apples produced and sold.

Now that agribusiness perceives the increasing economic value of establishing cannabis cultivars, there is a pressing need to navigate the plethora of available varieties and evaluate their agronomic strengths and weaknesses.

Simultaneously, we must ascertain what we—the founders of a burgeoning industry—and, more importantly, our evolving society will strive to accomplish throughout our ongoing journey with cannabis. Our “rush for the golden plant” has only just begun.