Our history of “Kush” begins in the rugged Hindu Kush Mountains of northeastern Afghanistan, homeland of the world’s finest hashish. Legendary Afghan “Primo” was created by sieving crushed dry cannabis flowers—a technique well-adapted to the arid and often cold climates along the temperate southwestern fringe of Central Asia. During the 1960s and ’70s, many adventurous wanderers passed through Afghanistan as they followed the “Hippie Trail” from Europe to India. By the time Westerners reached the region, landrace hashish varieties had been grown and processed with traditional techniques for generations, and both the farmers and their crops were well adapted to the arid, alpine conditions.

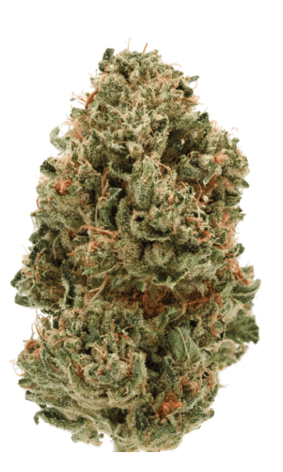

Travelers familiar with cannabis plants growing in other regions soon realized that the Afghan varieties looked different: shorter plants with broad, dark green leaflets and stout branches supporting denser and leafier inflorescences covered with copious resin glands that sparkled in the intense sunlight. Most significantly, the aromas and flavors of Afghan hashish flowers were of an entirely different spectrum—more resinous, earthy, dank and skunky smelling when compared to the more herbal, spicy, flowery and fruity aromas 1970s sinsemilla marijuana smokers were learning to relish—and varieties from the Hindu Kush formed a class by themselves.

Coming to North America

From the late 1960s into the early ’80s, travelers and smugglers brought seeds of this amazing new “hash plant” home, and the first domestically grown Afghan cannabis sprang up in Western gardens. These early home growers were already familiar with New World landrace varieties such as Colombian, Jamaican and Mexican, along with Old World Indian, Nepali, Thai and even African. The biodiversity of introduced landraces was at its zenith.

These traditional sinsemilla varieties were imported from sub-tropical latitudes, and most matured later in autumn than was practical across much of temperate North America; many plants succumbed to winter frosts before they could fully mature. All these early sinsemilla landraces shared the common traits of taller growth with narrow, light- to medium-green leaflets spaced along longer branches with lax inflorescences (within which resin gland production was largely limited to the flower bracts, rather than being shared by the small leaflets). These early narrow-leaflet landraces produced an array of fragrances and flavors that enhanced and modified a comparably diverse array of enjoyable and potentially therapeutic effects. But, they often produced only small amounts of potent flowers.

By the early 1970s, crosses between these imported landraces had begun to yield improved narrow-leaflet hybrid varieties grown from seed that had larger and more potent flowers than their predecessors. These gained popularity quickly, and by the end of the decade, potent and flavorful narrow-leaflet hybrids like “Original Haze” and “Kona Gold” had become legendary in their own right.

Most early domestic Afghan growers kept their coveted “hash plant” seeds close to home, but eventually the seeds were spread far and wide. By the late 1970s, they were rapidly gaining popularity in isolated regions across North America. Afghan landraces expressed several key agronomic traits that were advantageous to prohibition-era outdoor sinsemilla growers. The most economically favorable traits included short stature, early maturation and enhanced resin gland production. Hybrids between the recently introduced Afghan varieties and the wide range of extant narrow-leaflet landraces produced some spectacular results. Earlier-maturing, vigorous plants yielded heaps of dense, pungent and potent flowers. What more could a grower want?

OG Kush Origins

Privacy and security, that’s what. As the war on drugs heated up, growers sought refuge indoors under lights. Traditional, later-maturing, tall and sparse narrow-leaflet sinsemilla varieties proved challenging to grow indoors, and shorter, faster-maturing hashish plants with dense flowers offered a seemingly perfect solution. Hashish x sinsemilla hybrids, paired with high-intensity lighting, became the unstoppable force that spread urban cannabis cultivation worldwide. This is where the modern “OG Kush” story begins.

The “OG Kush” lineage is a product of prohibition-era indoor cultivation. In the 1990s, Florida resident Matt “Bubba” Berger grew a “Northern Lights” cutting he would later dub “Bubba” after the term of endearment bestowed upon him by his grandmother. Berger also acquired a local Floridian favorite known as “Krippy” or “Supernaut” from local grower Alec Anderson. As the story goes, “Krippy” was renamed “Kush” after a friend of Berger’s claimed the dense, colorful, round buds looked like something he called “Kush Berries” with no apparent knowledge of the important impact of Hindu Kush landraces on traditional sinsemilla varieties. And, it is entirely possible that the name “Kush” was subconsciously associated with cannabis. Most likely, the “Northern Lights”-based variety “Bubba” parent was more closely related to a true Afghan Hindu Kush landrace than what would eventually become the famous “OG Kush” clonal variety.

For years, “Kush” remained a well-kept secret shared within an insular community of Florida growers. It did not gain its now-international fame until it was smuggled to Los Angeles and placed in the hands of Josh D, whose name has become synonymous with the modern-day “OG Kush” clone. Josh D became the guiding force who ultimately perfected the cultivation techniques required to grow this agronomically challenging plant. “OG Kush” is not an easy plant to grow: It is sensitive to light and nutrient levels, susceptible to pests and when stressed, produces a few male flowers and accidental seeds. Josh D shared cuttings and knowledge with numerous friends and growers who would eventually spread “OG Kush” cuttings around the world.

Profile, Heritage & Evolution

Though the primary origins and lineages of “OG Kush” heritage are still shrouded in mystery, its terpene profile and intense effects suggest it is closely related to many other Afghani varieties—with which it shares some advantageous and some deleterious traits. Because it spontaneously develops occasional male flowers (resulting in self-pollinated seeds), and the resulting offspring are remarkably similar to the “OG Kush” parent cutting, the inbred “OG Kush” family also accidentally spread through flower sales.

The intense aroma of “OG Kush” became such a marketing tool that many aspiring sinsemilla breeders could not resist crossing their varieties with “OG Kush” in order to capitalize on the burgeoning demand for extremely flavorful flowers. While focusing solely on fragrance, potency and retail appearance, many breeders unconsciously encouraged and proliferated some of Afghan’s much less desirable traits as well. The most detrimental of these traits include extreme susceptibility to molds, mildews and other economically threatening pests.

Members of the highly prized “Kush” family of hybrid sinsemilla cuttings are all distant relatives of hashish landraces imported from Afghanistan, and they all express many favorable parental traits from both their broad-leaflet Afghan and narrow-leaflet non-Afghan ancestors. The traditional pre-Afghan hybrids were descendants of narrow-leaflet landraces that mostly originated in semi-tropical climates, and over time had evolved natural resistance to a variety of pests, especially fungi. Traditional seed-grown, narrow-leaflet varieties matured late in autumn and often endured cold fog and drizzly rain without developing a touch of gray mold, and the mildews so common today were rarely seen on cannabis crops. Pre-Afghan varieties were susceptible to few pests and diseases, and rare infestations usually remained isolated.

On the other hand, Afghan landraces originated in a dry climate with few fungi, providing scant evolutionary pressure to develop resistance to fungal infection and resulting in populations that proved highly susceptible to fungal attack. Indoor grow room and greenhouse atmospheres are often considerably more humid than the outside air, and when varieties of Afghan heritage are grown indoors, they are most often compromised by pests and pathogens. This susceptibility has proven to be a dominant trait in present-day hybrids, and “OG Kush” and its relatives within the “Kush” family (as well as most other modern drug cannabis hybrids, whether rich in THC, CBD or both target compounds) have inherited this economically threatening trait. Today, susceptibility to these pests can result in catastrophic crop losses that will prove to be unsustainable in a normalized agricultural cannabis industry.

OG Influence

The “Kush” family (which would eventually be collectively known as “OGs”) produces some of the most highly sought-after and expensive cannabis flowers ever produced. Their contribution to the modern cannabis ecosystem has been beyond impactful. Resulting from its assimilation throughout much of the modern-day drug cannabis gene pool, and its resultant widespread influence on pop culture, “Kush”-based varieties have shaped the parameters of what many modern cannabis consumers seek from the plant. Yet these popular “Kush” varieties carry many of their original Hindu Kush landrace traits and still unintentionally harbor, aid and abet the spread of a host of dangerous pests and diseases. Of course, none of this dark outcome was predicted, everyone worked in good faith and nobody is to blame. However, a variety’s heritage is inescapable, and pest susceptibility impinges heavily on our industry as we move with our plants into a more regulated and highly competitive market.

The influence “Kush” varieties had on the cannabis gene pool, and why these influences spread so quickly, is a history firmly entangled in the web of prohibition. While we gaze into the future and seek directions for shaping our ever-changing relationship with the cannabis plant as it becomes an agricultural commodity, we should take into account both our modern societal needs as well as the rich history of our favorite plant.