When California bureaucrats began constructing a vision to expand the state’s legal cannabis market and redress the harms of prohibition on the heels of Proposition 64’s passage in 2016, it was music to John Casali’s ears. He’d been waiting for this moment for a long time.

At Huckleberry Hill Farms in southern Humboldt County, Casali began walking in his mother’s footsteps from a young age, helping her grow cannabis and vegetables and tend to an orchard in the 1970s on their single-family plot between the two small communities of Briceland and Whitethorn.

Casali says this mountainous region that he’s called home his entire life has become the epicenter of a multibillion-dollar state industry. It was also the bull’s eye that took the brunt of law enforcement’s war on drugs for many years before this current era of legal cannabis. Casali knows the tension of this history from personal experience.

In 1992, at age 24, Casali and his best friend became federal targets and were arrested for cultivating cannabis. He spent four years fighting for his freedom in court and then ended up serving eight years in federal prison followed by five years of probation.

Years later, when Casali returned to his family farm, the promises of legalization drew him to the regulated space. Huckleberry Hill was the fourth legacy farm in Humboldt to become fully permitted by the county and state.

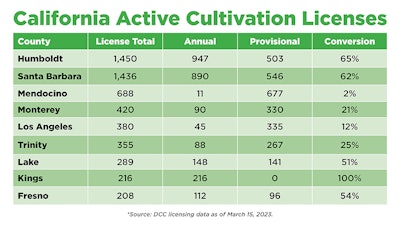

Humboldt County now has more active cultivation licenses than any county in California, according to state licensing data, as of mid-March 2023.

“Most of my neighbors and friends have been growing here illegally for the last 50 years,” Casali said. “And so, when they gave us the opportunity to enter into the regulated market, it really sounded like an amazing way of living—a way to live without fear, a way to sleep good at night.”

The fear of CAMP helicopters and prison time fell away, only to be replaced by long sleepless nights spent worrying over California’s new regulatory burdens.

As the owners of one of the smallest farms in California, Casali and his girlfriend, Rose Moberly, tend to 5,000 square feet of canopy. Even though it’s a small operation, Casali said it’s a tremendous amount work for two people, and, along with remaining compliant, that work consumes most of their everyday lives.

“And that’s OK, because we love growing cannabis,” Casali said. “It’s just—we’re doing the best we can and we’re still losing money.”

As wholesale and retail prices plummeted to all-time lows throughout many legacy markets during last year’s market correction, Casali and Moberly reported $50,000 in losses on their 2022 taxes for Huckleberry Hill. That’s $10 in the red per square foot.

While markets go through up and down cycles, Casali said much of the current pressure facing small cannabis operators in California stems from the state’s unfulfilled promises of legalization.

“Really what we’re seeing is just such overregulation, and just, it’s way more stressful being a permitted farm than it was being a traditional farm,” he said, adding that many of his neighbors have allowed their licenses to lapse and/or ceased cultivating altogether. “If they went back to the traditional market, one might guess that might be a way that they could survive here in the country.”

Pricing Problems

While spot wholesale flower prices peaked at roughly $1,500 per pound—an average for all grow types—during a COVID-related boom in mid-2021 in California, those prices fell more than 50% by the end of 2022, according to Cannabis Benchmarks, an industry source for cannabis wholesale pricing and analysis.

The average wholesale flower price was $654 per pound in January 2023, rebounding slightly from 2022 lows, according to Cannabis Benchmarks.

But, depending on one’s cost of production, California’s current market condition offers varying degrees of sustainable farming.

Take Glass House Brands, for example: The largest cannabis cultivator in California, with roughly 5.5 million square feet of greenhouse capacity in Southern California, including 841,000 square feet dedicated to flowering and 420,000 square feet to nursery operations, recently reported a fourth quarter 2022 cost per pound of $127. The publicly traded company anticipates its cost of production to fall below $110 per pound in the second half of 2023.

While sheer capacity remains a competitive edge, the majority of licensees in California don’t have that large-scale luxury. For many small farms in Northern California, cannabis that commands $700 on the wholesale market is a break-even point when factoring in various fees associated with a regulated market and supply chain, Casali said.

And with wholesale prices dipping below that mark in 2022, many cultivators dropped out of the regulated space. As of March 15, 2023, there were 7,063 active cultivation licenses in California’s market, according to the state’s Department of Cannabis Control’s (DCC) licensing portal. But that number is dropping daily—down nearly 500 active licenses from when Cannabis Business Times ran licensing analytics three weeks earlier (on Feb. 23).

| Date | Cultivation Licenses |

|---|---|

| Dec. 31, 2021 | 8,493 |

| Dec. 31, 2022 | 7,672 |

| Feb. 23, 2023 | 7,559 |

| March 15, 2023 | 7,063 |

While there’s a “little bit” of a rebound happening with prices, that rebound is incremental, said Genine Coleman, executive director at Origins Council, a nonprofit that advocates on behalf of small and independent cannabis businesses, including roughly 750 members in Humboldt, Mendocino, Nevada, Sonoma and Trinity counties.

“Right now, prices have been hovering right above or below production costs,” Coleman said. “And people aren’t making a living. They’re holding on essentially to try and maintain their license and weather the storm to get to the other side where there’s more market access.”

That greater market access may include direct-to-consumer sales, interstate commerce or federal legalization, but complex legislative solutions could take years to implement. Cannabis growers staring down rising costs and dwindling price points don’t necessarily have the luxury of waiting for those measures to materialize.

In the interim, to make matters even more oppressive, many cannabis producers simply aren’t getting paid. Coleman calls this a “credit” conundrum that’s spun out of control, with licensees reportedly unable to collect on delivery from other licensees. For example, when retailers don’t pay brand distributors at the point of purchase, then distributors can’t pay manufacturers, and manufacturers can’t pay farmers.

Among Origin Council’s 750 members in five counties, about 85% are owed money, Coleman said.

“It’s really challenging. There’s not a lot of recourse. I mean, it’s really kind of left to civil pursuits and nobody’s got money to leverage a lawsuit,” she said. “And then the other piece of that is you’re enforcing against your supply chain partner in California. You’ve got mandatory third-party distribution, no direct sales, you have to sell through retail. And so, you’re burning outlets. … We have a real market access problem.”

When industry players are left to enforce contracts on unpaid invoices, Coleman said, “The whole supply chain is in the process of collapsing, quite honestly—it’s that bad in California.”

Overproduction?

While Coleman and Casali painted a bleak outlook on California’s legalized space, recent market exits—from large multistate operators like Curaleaf to small-scale legacy operators—have led to a shrinking canopy statewide. But the extent of that decline in total canopy across California is less clear.

Overall, more than 1,400 cultivation licenses have exited the market since the start of 2022, according to DCC.

In an effort to contextualize the market supply implications of fewer active cultivation licenses, Cannabis Business Times requested current and past cultivation canopy figures from DCC on Feb. 23.

But the regulatory agency that oversees the world’s largest cannabis market did not have data on hand for how many square feet of cannabis canopy is currently licensed in their authority. As of March 16, CBT’s request had yet to be fulfilled.

Instead, industry stakeholders have relied on alternative methods to calculate their own statewide canopy capacity estimates based on exporting thousands of licenses, filtering and sorting different licensing types, and factoring hypothetical canopy sizes based on maximum square footage allowed for those types to determine the state’s supply trends.

Understanding a statewide market cannabis supply—whether that be licensed canopy capacity, plants being harvested, or simply an inventory of dried flower pounds available to processors—allows licensed operators to make more educated business decisions.

Private investor Aaron Edelheit, CEO of Mindset Capital, who confirmed his methodology with CBT, estimated that there was roughly 64 million square feet of licensed cultivation capacity in California as of March 14—down 22% from the more than 82 million square feet of licensed capacity in the first quarter of 2022.

My calculation of licensed cultivation capacity in California. Continues to plunge. pic.twitter.com/NJApXiW11x

— Aaron Edelheit (@aaronvalue) March 14, 2023

A DCC spokesperson told CBT it would take the department a few weeks to verify those estimates.

If prices are beginning to rebound as production capacity across the state continues to fall, an opportunity for growers of all sizes may be revealing itself.

Glass House, as an example on the larger end of the cultivation scale, intends to ramp up production with plans for further expansion of its cultivation capacity at its greenhouse in Southern California.

During a virtual investor conference on Feb. 23, Glass House co-founder and president Graham Farrar told listeners that California cannabis inventories are low and “people are sold out” on the heels of mass market exits.

“We’re currently selling it faster than we can grow it,” Farrar said. “And, as a result of that, we’re seeing prices move up, and frankly, we think back to a more sustainable level. For us, again, being on that left-hand side of the cost curve, the prices that we’re now at are very comfortable.”

In Humboldt County, Casali said an oversaturated market was the largest hurdle small farms like Huckleberry Hill faced in 2022.

“It’s the story of the day that California is in the crisis, but we tried to warn the regulators that this was all going to happen; you can’t continue to permit farms without federal legalization,” Casali said. “The oversupply problem is the single most biggest problem that California is having.”

But Casali and Moberly have their own reasons to be optimistic about the 2023 growing season.

Deploying Unique Cultivars

While some California growers have remained focused on many of 2022’s best-selling flower cultivars, like Wedding Cake and Gelato, Casali said small farmers in Northern California are deploying a market weapon that will keep them competitive: unique cultivars.

“The light at the end of the tunnel seems to be coming around the corner, actually,” he said. “We are seeing kind of an uptick in demand for small, sun-grown craft cannabis, especially with those farms that have created and bred unique cultivars.”

At Huckleberry Hill, that means unleashing Whitethorn Rose, a cross of Paradise Punch and Lemon OG that won Emerald Cup awards for ice water hash and live rosin. Another new cultivar called Riddlez, a cross of Whitethorn Rose and Zkittlez, won first place at the Ego Clash Invitational in Mendocino County.

Through various awards, Casali said Huckleberry Hill has generated new demand for those cultivars and recently received two orders for more than 600 pounds for harvest of 2023.

With nobody else in the world growing Whitethorn Rose—named after his farm’s location and girlfriend—Casali said he believes he’s found a path forward to navigate California’s ongoing market correction.

“What we’re seeing is all these family farms are starting to bring out these unique cultivars that are found nowhere else in the world, and really putting them into the marketplace and really getting a great response and a huge demand from the consumer,” he said. “And so, that’s really our pathway forward, and that’s what will enable the small farmer to survive.” In this unique genetic niche, Casali has found a counterpoint to the sheer scale that larger growers may use to their benefit in this competitive market.

In the meantime, Casali and Moberly have continued to hang on by their fingertips by thinking outside the box to cut costs and generate new revenue, from utilizing their own land and surrounding forest for mulch and nutrients to selling seeds and working with Humboldt County to provide tours on their farm.

Casali said he’s also focused on developing new relationships with retailers and other industry players who are better aligned with the values at Huckleberry Hill.

Licensing Issues Loom

Despite more than 1,400 cultivation licenses having exited the California market during the past 14 months, the state’s licensing landscape could dwindle further come July 1, 2023, when cultivators must have annual licenses or taken the proper compliancy steps to renew their temporary “provisional” licenses in order to continue growing.

This is not simply a clerical adjustment. The requirement mandates local jurisdictions conduct an environmental review of each cannabis operation’s compliance with the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) of 1970. In June 2021, the California Legislature approved a plan to funnel $100 million to local governments to oversee the permitting process for annual licensure.

Nearly two years later, Coleman at Origins Council said the local mandate remains largely underfunded, or, in some cases, funds haven't been utilized properly.

“The problem with this whole state framework is that you basically require local jurisdiction to have this discretionary authority over each and every project [review],” she said. “And so, you put the decision for every project in the hands of county staff, board of supervisors for certain levels of review, as opposed to utilizing something like a ministerial program where you’ve just got objective standards—the project either qualifies or it doesn’t.”

Certain jurisdictions, like Kings County (north of Bakersfield), where all 216 active cultivation licenses had converted to annual licenses as of March 15, have done better jobs than other municipalities in assisting cannabis businesses in completing the time-consuming and complicated environmental studies around the impacts of their operations.

In Mendocino County, 11 of 688 active cultivation licenses, or roughly 1.6%, had converted to annual permits as of March 15.

Here’s a breakdown of the nine California counties that have the largest number of active cultivation licenses and where they stand on annual conversions:

The Mendocino Cannabis Alliance (MCA), a trade association representing cannabis operators in the county, sent a 16-page letter Feb. 8 to Gov. Gavin Newsom and DCC Director Nicole Elliott, and copied various state legislative leaders, urging they intervene in what the alliance called the county’s “failure to establish a process capable of moving small and legacy cannabis cultivators towards state annual licensure.”

The letter states that Mendocino cultivators are at “imminent risk” of losing their state licenses, which would undermine Prop. 64’s intention to provide a “just transition” for legacy operators. Furthermore, the letter claims that nearly six years after an ordinance to regulate cannabis cultivation, the Mendocino Cannabis Department “has not meaningfully moved forward to process local cannabis permits, cannabis permit renewals, or documents necessary for CEQA compliance.”

While the DCC allocated nearly $17.6 million—of the $100 million in state grant funding—to assist Mendocino’s local government with permit processing, Michael Katz, the MCA’s executive director, wrote in the letter that his trade association believes there has been a lack of public accounting for how that money has been or will be utilized.

“The bottom line is that there is no functional permit program in Mendocino, and no plan to create one,” Katz said in a Feb. 8 press release. “We cannot move forward if the county continues to obstruct local licensees. We need the state to intervene, and intervene now, if our legacy cultivators are to survive.”

Earlier this week, the Mendocino County Board of Supervisors signaled a shift in its approach to streamline the permitting process as much as possible, Katz told CBT.

Coleman, who lives in Mendocino County and cultivated cannabis for more than 20 years, said the county’s approach had been obstructing the permitting process up until this point.

MCA’s letter noted that Mendocino officials provided a timeline on Jan. 23, 2023, that aimed to enable 256 “prioritized” operators, among 841 active cultivation operators at the time, to meet the July 1, 2023, statutory deadline for annual licensure or provisional renewal. There was no immediate plan for the other 585 licenses, the letter states.

But in less than two months since then, more than 150 active cultivation licenses in Mendocino County have already exited the regulated space. And the likelihood of their return appears bleak: Cultivators must maintain their provisional licenses in continuity or start over. That means they’d not only need to pay all the upfront fees but also be CEQA-compliant from the onset of reentry.

“These people are all capital expenditures in and zero ability to pull their money out,” Coleman said of provisional licensees. “They can’t sell their business. They’re not annually licensed. They’re incredibly vulnerable. They’ve got no due process rights. This isn’t statute for provisional licensing. And so, they’re so vulnerable. They’re hundreds of thousands of dollars in, six years in, and if they don’t maintain their provisional license, they’re screwed—they’re done. The business is done. They’re probably selling their land and moving.”

Coleman predicts that there could be a falling out for roughly one-third of the Emerald Triangle cultivation license holders without changes to the state’s permitting structure.

Neighborly Hardships

The legacy growers over in Humboldt, whose local government received $18.6 million in grant funding, have been more successful in converting to annual licenses but roughly one-third remained with provisional permits as of mid-March.

At Huckleberry Hill, which did receive annual licensure, Casali said his farm still has challenges ahead, but what keeps him up at night these days is the thought of his struggling neighbors.

“For me, it’s seeing my neighbors and friends having to deconstruct something that they created in hopes of living the American dream, and they put all their money and all their time and energy into creating their legal farms,” he said. “And now some of them are going to actually have to sell their properties and move away. And these are my family. This is a really tight-knit community that always had to rely on one another. And to see that kind of falling apart and people depressed and just unknowing of what the future holds is really what keeps us up at night.”

While cultivation license exits could potentially help those who survive, who will in turn control a larger percentage of the state’s shrinking supply, that’s not what the cannabis community up in Humboldt is all about, Casali said.

Under the unformal motto of, “It’s never about one of us; it’s always about all of us,” a deep-rooted tradition in Humboldt is to lend a helping hand to a struggling neighbor, Casali said.

“And to kind of break that tradition, it’s very saddening, and disheartening and not the way we want it to be,” he said. “It’s like a big puzzle on our table, and we’re trying to figure out how to put the pieces together. But, because of all the shenanigans with the state regulations and things that are happening, just, the pieces aren’t fitting.”