Every year, cultivated and wild plants, including cannabis, carefully time the start of flowering to ensure a successful exchange of pollen and the production of large quantities of viable seeds. Domestication of plants usually involves the selection of individuals with “preferable” traits, of which flowering time is key by enabling cultivation at a wider range of environments, particularly higher latitudes where weather and daylength fluctuate greatly depending on the season. Despite being cultivated since ancient times, our most advanced cannabis cultivars still have a wild-type (undomesticated) flowering time.

Recent work from the team at Aurora, a global cannabis licensed producer, has uncovered a single-letter change in the sequence of a gene that likely explains why some cannabis plants have different flowering times. The ability to manipulate flowering time in cannabis could revolutionize cultivation practices and significantly reduce the environmental impacts and production costs in the cannabis industry.

Most advanced cannabis cultivars initiate flowering when the amount of light they receive is reduced from approximately 18 hours (long days) down to about 12 hours (short days). This process if referred to as “triggering,” and cultivars that respond to this change in daylength are called photoperiod sensitive. This type of flowering works well in indoor and greenhouse facilities where growers can control the duration of the day. Importantly, photoperiod sensitive cannabis remains vegetative when kept under long days, allowing growers to maintain mother plants from which they can get clones for production.

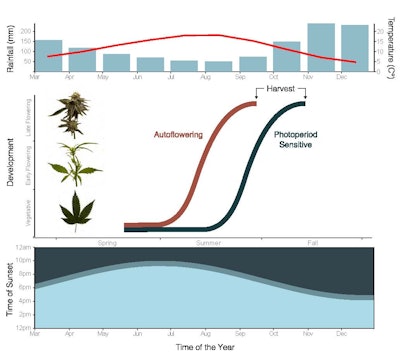

Indoor and greenhouse cultivation, however, are very energy intensive due to the use of artificial lights and cooling/heating systems to maintain optimal growing temperatures. Although indoor cultivation of clonally propagated plants allows year-round production, its carbon footprint and energy and labor costs represent a major challenge for this new industry. Photoperiod sensitive cultivars are poorly adapted for outdoor cultivation in northern latitudes, like in Canada, where Aurora is based. The shortened day length required to initiate flowering does not occur until August, thereby pushing harvest to October when the risk of frost and pathogen damage increases significantly (see Illustration below).

A less widely grown type of cannabis, usually referred to as autoflowering, flowers regardless of day length (see Illustration above). Autoflowering cultivars flower at a determined number of weeks after germination, which means growers can control flowering time by selecting when they sow the seeds. By selecting an appropriate sowing date, cannabis can be cultivated outdoors with a much lower environmental impact and in a much wider range of latitudes, including Canada. Autoflowering cultivars, however, typically have significantly lower flower quality, yield, and cannabinoid concentrations compared to photoperiod-sensitive cultivars. To breed new cannabis cultivars that combine the autoflowering trait with high-quality flower, a precise knowledge of the genetic mechanisms that explain the autoflowering phenotype is needed.

In a preprint paper published in March, the team at Aurora propose that a malfunctioning gene in the circadian clock of cannabis is responsible for the unusual yet more predictable flowering time of autoflowering cultivars. All organisms contain internal clocks that help them time biological events to specific times of the day, year or life cycle. In plants, the circadian clock helps integrate changes in daylength with developmental processes such as flowering. Cannabis is no different; the circadian clock signals the time to flower when daylength begins to shorten in the late summer. By using genome-wide association studies and cutting-edge molecular biology approaches, the Aurora team characterized a natural mutation in PRR37, a gene in the pseudo-response regulator family that plays a central role in plant’s circadian clock. The PRR37 mutation disrupts the standard processing of its messenger RNA molecules and severely limits the production of functional PRR37 protein. As with any clock, a malfunctioning cog will disrupt proper timekeeping, and in this case, make cannabis plants flower much earlier than normal.

Knowledge of the precise mutation that causes autoflowering in cannabis (patent pending) is allowing Aurora to fast-track breeding of elite-quality autoflowering cultivars that can be grown commercially outdoors, giving growers more options and use fewer resources to grow cannabis.

Dr. Jose Celedon has worked in plant genomics and terpene biochemistry for more than 10 years in different academic and industry labs. He currently leads the Genetic team at Aurora to develop the fundamental knowledge to breed the next generation of cannabis cultivars.

Keegan Leckie is a research scientist in bioinformatics who has been working for Aurora Cannabis since 2018. Keegan works in Aurora’s breeding program focused on developing elite cannabis cultivars for both medical and recreational channels, as well as developing cultivars for a more sustainable cannabis industry.