Every morning in the misty hills of southern Humboldt County, John Casali wakes up at 5, brews a pot of coffee and walks through his cannabis garden. Huckleberry Hill Farms is the very picture of the Emerald Triangle’s small-farm agriculture, a second-generation plot of gently rolling land with just under 5,000 square feet of cannabis.

On his morning walks among the plants, he makes a point of touching each one. Casali grew up here, watching his mom grow a cultivar that he now calls Paradise Punch. Every cannabis plant at Huckleberry Hill Farms is crossed with Paradise Punch, a horticultural ode to his mother’s influence. He walks past rainwater catchment ponds filled to the brim and tends to new cultivars like White Thorn Rose and Sweet Marlene, named after his mother.

In June, typical mornings might include visits from distributors or tourists. But very little in 2020 is what you would call typical. The coronavirus outbreak has not spread into the rural ranges of northern California on the concentrated, New York City-scale, but the attendant economic pressures sure have. Casali does not know if he will be able to welcome visitors to his farm this year, a major blow to the business model that brought him into the licensed marketplace after a lifetime on the fringes. Those tours are the modern foundation of this long-running farm. They are one way of setting Huckleberry Hill apart from the rest of the cannabis market.

“One of my biggest regrets is not being able to share that with people,” he says. “That’s a huge part of this farm, being able to share the story of the Emerald Triangle.”

It’s a story that arcs back through decades of what farmers now call “the traditional market,” the unlicensed landscape that blended a back-to-the-land ethos with the communal nature of cannabis. And it’s a story that persists in new forms today. Casali was awarded his temporary cultivation license in early 2018. As the state continued to hone its regulatory oversight, he picked up a permanent cultivation license the following year. Working in the licensed market has not been as simple as that, though.

He holds one of the 5,350 cannabis cultivation licenses issued by the California Department of Food and Agriculture (as of April 27). But getting a license in this competitive marketplace is only the latest chapter in the ongoing story. Now, Casali says, it is more important than ever to share what’s happening in California.

“What I am seeing here at this farm is, as the market becomes more competitive with bigger and bigger farms coming online from southern California, the price is getting pushed down, which makes it a lot harder for this farm to be profitable,” he says.

In February 2018, the California Growers Association (CGA) published a report titled “An Emerging Crisis: Barriers to Entry in California Cannabis.” The document outlined an economic imbalance that would preclude much of the traditional cannabis market from entering this newly regulated regime. The association listed oppressive tax burdens, “license stacking” and a multi-layered bureaucracy as barriers to entry. From the jump, larger businesses quickly began assembling smaller-scale licenses to cover more acreage under one entity—and on one property.

“The current system will not achieve its goals without fundamental and structural changes that allow small and independent businesses to enter into compliance,” the CGA wrote in its report.

Two years have flown by since then.

Casali says there’s plenty of hope to go around, but it’s a complicated picture. He spent 10 years in prison, serving a mandatory minimum sentence for growing cannabis in the ’90s. Now, he is a licensed business owner partnering with Flow Kana and Willie’s Reserve to share the plant his mother once grew in secret. Clearly, the legal landscape is working on some level.

“It’s something I take a lot of pride in,” he says. “It’s something I love to do, and it’s the first time in my life I’ve ever been able to share something that I’ve been doing my whole life.”

But how long can this continue?

Pain in the Bottleneck

On April 23, a group of cannabis business organizations published an open letter to California Gov. Gavin Newsom, urging action on behalf of both social equity businesses and the licensed marketplace. It reads like an update to the CGA report from 2018. Its tone is urgent.

“The vast majority of legal cannabis businesses have been struggling since the implementation of Proposition 64,” according to the letter. “Now, when our state, country and the world is facing its biggest public health crisis in generations, we are asking you to consider tax relief for the cannabis industry to ensure our businesses make it through the COVID-19 crisis and are able to compete, much less thrive.”

Adam Spiker, executive director of the Southern California Coalition (SCC), a signatory to the Newsom letter, says that the novel coronavirus outbreak and its economic squeeze aren’t the only sources of pain for the cannabis industry. But they’re certainly not helping.

“These issues started the moment people got licensed under Prop. 64 and MAUCRSA [the Medicinal and Adult-Use Cannabis Regulation and Safety Act],” Spiker says. “They’re probably being elevated under COVID-19, and they will be there post-COVID-19. The price point for legal cannabis is way out of whack with illegal cannabis. It’s at or more than double the price.” And now, more than in recent history, customers are attuned to price.

The history of legal cannabis in California follows a simple progression: Prop. 215 ushered in a “gray market” for medical cannabis sales in 1996. In 2016, voters passed Prop. 64 to legalize adult-use sales. In 2017, legislators blended the medical and adult-use markets under MAUCRSA. Adult-use sales began Jan. 1, 2018. The idea was to legitimize and regulate the state’s decades-long history of cannabis farmers and sellers. Yet, the current climate leaves thousands of operators continuing to work the traditional market in the state.

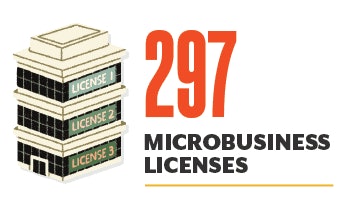

This past fall, the United Cannabis Business Association (UCBA) published a report that showed a three-to-one ratio between the illicit market and the licensed market. The report claimed that 2,835 illicit “sellers” were actively feeding into demand in the state. At the time, 873 licensed retailers were operating. (As of May 20, the state has issued 723 retail licenses, according to Alex Traverso at the Bureau of Cannabis Control, the discrepancy being a product of some microbusiness license holders operating retail storefronts as well.)

Spiker points to the operating principle of competition in a commercial marketplace. That’s what’s missing from California, he says. Taking price point alone into account, it’s virtually impossible to compete with growers and sellers who aren’t shackled by high tax costs and compliance fees.

“In the vast majority of cases, the reward for getting a license has been pain for that operator,” he says. “Part of being licensed is you’re making a commitment to no longer do things in the gray market that they all used to under Prop. 215 and the collective model. You can only operate in the legal ecosystem, and they’re not able to compete. There are just not enough consumers purchasing legally.” If the question is one of getting consumers to choose the legal landscape, price is important.

And on top of price pressure, more than 60% of the state’s municipalities have maintained some form of moratorium on cannabis sales. Half of the state’s counties have done the same. (In many cases throughout California, “unincorporated communities” are governed by county rules.)

“There’s a bottleneck on legal access, a true bottleneck,” Spiker says. “I’ve heard state regulators, many who are experts in the realm of growing, tell me that we’ve probably licensed a handful times more than all the product we would need to consume if everything was captured in the legal market currently. We might have five times more licensed [businesses] than we need already, but it’s still our job to give them the best chance to compete and have a level playing field. And if there’s too many of them, unfortunately, that’s what the free market is for, right? Who does a better job is going to stick, and who doesn’t is probably going to go to the wayside. But, damn it, they deserve a fair playing field. I would argue that they don’t have one right now.”

Casali, in Humboldt County, where New Frontier Data estimates 27% of the state’s cultivation licenses are clustered, agrees with the supply-and-demand argument: “You have this giant funnel, and then it all gets bottlenecked at the retail market. They need to have thousands of retail shops within California. That would eliminate some of the illegal shops that are happening, like in L.A. and elsewhere.”

In December 2019, the Los Angeles Police Department raided and shut down 24 illicit cannabis dispensaries, seizing $8.8 million in unlicensed products. The UCBA report warned, however, that raids tend to move illegal actors from one shuttered storefront to another. It’s whack-a-mole on a statewide scale.

In the world’s largest cannabis market, the consumer’s line between the licensed, legal marketplace and the oft-convenient illicit marketplace is blurred. For businesses trying to lure those consumers to the licensed cannabis space, the result is a burdensome set of costs (taxes and compliance fees) that make it much more difficult to operate in the legal arena. In the grand scheme of things, licensed businesses are still competing against illicit dealers—who bear none of the same costs and can get away with lower price points for their customers.

Educate With Appellations

As the coronavirus pandemic continues to crunch an already precarious economic situation, Nik Erickson says that growers in California have been turning to white labeling for some sort of financial lift. Erickson is the owner of Full Moon Farms, another small-scale operation with two separate properties in Humboldt County. He grows 44,000 square feet of cannabis plants in different microclimates, each capturing a unique suite of advantages. In recent weeks and months, white labeling has “exploded,” he says.

White labeling is the practice of selling products to a purchaser, who will then use their own branding (rather than the seller’s original branding). As uncertainty crowds out the marketplace, growers and retailers are working out futures contracts and securing distribution well ahead of time.

“Right now, the market is still kind of screaming for the gas,” Erickson says. “The OGs, and Headbands and Sour Diesels, still have a strong marketplace.”

His team sets aside 80% of the Full Moon canopy for those northern California stalwarts. The other 20% is planted for pheno-hunting and “exotic” cultivars like Ice Cream Cake and Gelato.

“There are a lot of 10,000-square-feet-and-under craft farms here that are having a difficult time in the marketplace because of the financial strains put on them,” Erickson says. “They’re just not at scale, to keep up with a lot of the finances. [The Humboldt County Growers Alliance is] looking at cooperative models, independent branding, trying to get into more of a vertically integrated supply chain for the little guys so they can get a little more value out of each pound.”

This is the central issue, he says: That familiar refrain of price point competition. The thinking is that if smaller growers can work their operation into a larger vertical infrastructure, the value per pound will increase. This is where outside brands can play a role, using small growers’ flower to develop new products for the market at a lower cost.

“We’re kind of at a scale right now to where what we’re doing is white labeling most of our product.,” Erickson says. “But there is a lot of brand saturation out there right now. Especially like in the eighth markets. I think the biggest catalyst for the small farmer is going to be federal legalization, because the California market is fairly saturated.”

Across the state, much of the legal market is value-driven by the consumer. Price matters, and consumers willing to pay to participate in the licensed dispensary setting tend to seek the most bang for their buck: High THC content, low cost. “It’s not in line with the craft grower,” Erickson says.

But that can change. Legal cannabis remains a young, still-maturing market. California is on its own timeline in how far back its cannabis legacy runs. The traditional market is deeply embedded in certain regional cultures throughout the state. Erickson says it’s vital for licensed growers to look into the future for a broader, more curious consumer base. That, he insists, is where California’s struggling craft growers might be able to place their hopes.

“I think that when the markets open up nationwide, and maybe globally, even though the market share is going to be smaller for that craft product, the overall market will be so much larger that the craft farms will actually start seeing some of that value association to how they farm,” Erickson says.

The California Department of Food and Agriculture has been tasked with designing and overseeing the Cannabis Appellations Program, a long-term plan that came out of the early Prop. 64 legalization measure. It’s a model borrowed from the wine industry, where geographic and climatic appellations help inform the marketplace of a certain product’s provenance. It’s at once a regulatory method to categorize businesses and a helpful marketing device. Places like the Emerald Triangle are an easy example: The history is already there. And growers like Erickson and Casali see formal appellations as a powerful tool to distinguish the small craft grower from the multistate operator. It will also inform the customer who’s deciding between buying from an acquaintance in town or buying from the licensed dispensary down the street.

“Having appellations on record in the California market will provide trustworthy information to consumers about where and how the cannabis was produced,” says Rebecca Forée, communications manager for the CalCannabis arm of CDFA. “And the marketing of the origin of cannabis may be of assistance to consumers with their purchasing decisions, and it will support cannabis cultivators who choose to differentiate their cannabis products,” she adds.

Following a May 6 public hearing on the topic, Forée expects additional public comment periods (beyond CBT’s print deadline). If all goes according to the mandated schedule, the regulatory rules that will govern appellations will go into effect Jan. 1, 2021. From there, it’s anyone’s guess as to when the actual appellations will come into being.

Tax Burden

Foregrounding those long-term questions is the matter of tax rates.

Gov. Gavin Newsom and the state legislature have openly courted tax restructuring conversations with the cannabis industry, but it remains a divisive question in the legislature and in the private sphere. Last year, State Assembly member Rob Bonta’s A.B. 286 tax reform bill picked up momentum (before ultimately stalling in committee), and cannabis growers are hopeful that meaningful action is just on the horizon.

Stakeholders in the debate, such as legislators and labor unions, generally demand a revenue-neutral plan—something that won’t disturb the flow of tax revenue toward public health, safety and the environment. For the 2020-2021 fiscal year, Newsom allocated $332.8 million in cannabis taxes (total taxes paid to the state, minus regulatory costs) to those public sectors.

In January, the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration increased the markup requirement from 60% to 80%, “which only expands the tax burden for the industry when it gets to the all-in number,” Spiker says. (A.B. 286 would have dropped the 15% excise tax to 11%.) Right now, California taxes include: a cultivation tax of $9.65 per ounce (dry weight) of flower ($154.40 per pound), a 15% excise tax and a 7.25% sales tax. From there, many local municipalities add their own excise tax rates to the bundle.

Each point of taxation not only adds a financial cost but ties up the cash flow along the legal supply chain. Spiker lauds Newsom’s stance on the matter thus far.

The argument, Spiker says, is that a lesser tax burden would galvanize the legal market’s competitive price point. The rise in consumer transactions would offset any purported loss to tax cuts. “At the end of the day,” he says, “if the all-in tax burden to a legal operator is in the neighborhood of 40%, locally and at the state, those numbers are going to get factored into the end price point for the consumer. As we’ve seen right now, that price is at least double what their illegal competition can sell it for. We’re not competing. We’re trying to push for tax relief, not tax restructuring.”

And as the state ramps up its social equity licensing, Spiker says that inertia on this topic sets up those new businesses to fail.

Even for established growers like Casali, the math is often difficult to overcome. He points out that higher-quality “AAA” flower may sell for $900 per pound in California. He ballparks $300 in costs that will come off the revenue, but he’s also quick to point out that the entire plant isn’t producing AAA product. It may only be 20% AAA product. The rest of the plant commands a lower price, which includes $500- or $600-per-pound flower that may be used in white-labeled pre-rolls. Each plant is a case study in how the regulated market impinges its own competition with the unlicensed market.

“Really, at that point we’re running at a loss,” Casali says. “Between 70% and 80% of our product, with all the different expenses that we incur, really can be sold at a loss. That’s encouraging farmers in the legal market to maybe participate in the traditional market. …. It behooves me just to throw it away and not deal with it at this point. But I want to be able to utilize all the products off of my farm.” He wants to sell to the legal market, but the tax structure makes it less beneficial than other options.

Hope Springs, Questions Abound

Two years ago, the California Growers Association warned of just such a picture: Prices being driven so low against regulatory costs that were skyrocketing, creating a great knot of economic burdens for smaller farms in the state. An emerging crisis. Whether that crisis is here to stay or is slowly concretizing as the years go on remains to be seen.

“Unfortunately for a lot of farmers that have employees that have a lot of overhead, they’re struggling with the lower price point, and it’s going to be really hard for them to survive,” Casali says. “And this year in particular, I think we’re going to see a lot of the small farmers in the Emerald Triangle not be able to continue forward.”

According to New Frontier Data, 47% of all California cultivation licenses are clustered in the Emerald Triangle—the state’s northern region comprising Humboldt, Trinity and Mendocino counties named for its decades-long cannabis cultivation history and notoriety. Many of those businesses are small farms with a few thousand square feet of cannabis canopy. After factoring in the other great outlier, Santa Barbara County, near Los Angeles, those four counties alone account for 70% of cultivation licenses in the state. What does that mean?

The state has a long way to go before its licensed cannabis market matches the girth and historical gravitas of the traditional market.

In the meantime, there’s no doubt that the coronavirus pandemic has colored the relationship between commercial enterprise and consumer base. What will retail look like in the future? How will supply chains bend and twist to meet emerging economic pressures? The list of unanswerable questions runs long in the summer of 2020.

In cannabis, the problem is compounded by the federal government’s hesitation on things like the Secure And Fair Enforcement (SAFE) Banking Act of 2019 or the Strengthening the Tenth Amendment Through Entrusting States (STATES) Act—measures that would turn the state-legal landscape into a normalized business platform. In most states, cannabis businesses were declared “essential” early in the crisis, which is a good sign. Growers like Casali, who’s been in the game for decades, know all too well the importance of good signs. They don’t come around every day, but sometimes all that’s needed is a fleeting moment of hope.

“I just remembered the day I stepped out of prison, how appreciative I was just being able to smell clean air and how appreciative I was of just being free and seeing the green leaves on trees or smelling flowers in my yard,” Casali says. “It’s similar to what people, I think, will take from what they’re experiencing now. And I sure hope they do. We have to remind ourselves once in a while that life is short. And we need to appreciate every single day.”