Direct-to-consumer cannabis sales are alive and well in the California market—just not in the regulated space.

For small, craft farmers like Tamara Kislak, owner and operator of That Good Good Farm in Mendocino County, and her licensed neighbors in Northern California, that means options to sell cannabis are few and far between.

Before this current era of legal cannabis in the Golden State, starting with the passage of Proposition 215 (the Compassionate Use Act of 1996), many cannabis transactions involved face-to-face relationships among farmers and consumers.

Now, under Prop. 64 and the California Legislature’s subsequent Medicinal and Adult-Use Cannabis Regulation and Safety Act (MAUCRSA), the state requires licensed growers to work through distributors to get their products in front of consumers or to vertically integrate with distribution or retail licenses of their own.

But for the small legacy growers in many parts of the Emerald Triangle, and elsewhere, a key challenge is simply volume. The supply chain in the world’s largest cannabis market does not incentivize small-batch cannabis harvests. When distributors make their money as a percentage cut, they want the prices from growers as low as possible so they can move as much volume as possible.

“It’s the classic middleman situation,” said Kislak, whose green thumb in Mendocino includes 10,000 square feet of licensed cultivation capacity, which is divided among terraces throughout her family’s 300-acre property of undeveloped forest overlooking the Anderson Valley.

While Kislak has cultivated cannabis since the 1990s, she’s been on her current family farm since 2009 and applied for a local cannabis permit in 2018. During 2022’s economic headwind, she grew no more than 200 pounds. Many distributors “don’t even want to mess with us,” because it’s not worth their time, she said, while smaller distributors are at risk of going out of business.

In the licensed market, Kislak said she’s paid anywhere from 10% to 22% in distribution fees. That’s before retail markups, meaning That Good Good commands a smaller return on the final selling price.

“We’re stuck in this crazy situation where we’re legally mandated to work with distributors, and we’re not even going to be able to get distribution,” Kislak said. “It’s not a state-run thing. I’m not pushing for a state-run thing.”

Adding to the complexity of California’s regulated supply chain, many vertically integrated distributors often avoid partnering with craft growers who are seen as competition to their own product, leaving some farmers in the mountainous regions of the Emerald Triangle with few options. From zoning restrictions to limited resources, Kislak knows this burden well.

While microbusiness licenses are available for small-scale operators who want to add distribution, retail or manufacturing capabilities alongside their cultivation footprint, legacy operators are often bound by their location, she said.

“Many people who chose their properties back when we were being hunted by helicopters don’t have that option because of zoning or just the sheer cost of the types of buildings that you’d have to build to be allowed to have distribution on-site,” Kislak said.

As California moves into its sixth year of legal adult-use cannabis sales, the decades-long legacy of its underground cannabis economy continues to shape the very foundation of this new industry.

Getting Creative

Kislak and a couple dozen of her neighbors began thinking outside the box more than a year ago to help provide greater returns on the retail price of their products through an online sales and delivery platform that has opened a more direct channel between Mendocino County growers and residents in Sacramento, Butte, Monterey and Mendocino counties: MendocinoCannabis.Shop.

The platform, which launched last year, includes 24 farmers who are also members of the Mendocino Cannabis Alliance (MCA), a cannabis trade association that provides guidance to operators in the county.

Although legacy growers who once enjoyed the pleasures of a farm-to-table model now face a statutory framework that has created separation between the cultivator and consumer through retail, cooperative opportunities like MendocinoCannabis.Shop have helped mitigate some of the costs associated with third-party distribution and difficulties in finding shelf space, MCA Executive Director Michael Katz recently told Cannabis Business Times.

While MendocinoCannabis.Shop is a direct-to-consumer style model, because it involves members collaborating with their licensed infrastructure to provide a higher return to producers, it’s “still not actually direct to consumer,” and that distinction is important, Katz said.

“This platform is really just one retail outlet that has provided additional revenue streams for our producers that they would not have had otherwise, at a higher rate of return than the traditional wholesale/retail environment generally provides, but it is not a silver bullet,” he said. “We are still competing against unregulated products that are completely untaxed and untested that to the average consumer seem comparable.”

To connect with consumers, Kislak often visits with That Good Good’s retail partners and makes herself available during on-site events for that face-to-face interaction.

But, by and large, California’s licensed retailers often do business with one large distributor to fill their shelves with “megabrands” rather than committing the extra time and effort to work with small cultivators and individual brands, Kislak said.

Player Dynamics

When illicit markets continue to thrive following legalization, this is not happening in a vacuum. Licensed operators often point to the additional costs and time associated with doing business in a regulated market, from high excise taxes to navigating licensure, attending government meetings and simply abiding by compliancy measures not seen in other agricultural markets, as important variables in the big picture.

In California, player dynamics have been partly responsible for instability in the supply chain, which includes roughly a 7-to-1 ratio of cultivation to dispensary licenses statewide. As of March 23, the state had 7,029 active cultivation licenses and 1,122 storefront retail licenses.

With an imbalance in supply and demand throughout much of California’s legal marketplace, prices plummeted during an inflationary market in 2022, which has been disadvantageous for many cultivators staring down production costs that no longer align with profitable margins.

RELATED: California Cannabis Operators in Peril as American Dream Turns to Nightmare

But whether licensed retailers hold the upper hand in California’s current market is a question that first needs context, said Hirsh Jain, founder of Ananda Strategy, a consultancy that represents many of California’s cannabis retailers and advises operators across the supply chain. Jain also chairs the Los Angeles Cannabis Chamber of Commerce and serves on the California Cannabis Chamber of Commerce.

“Rather than [a 7-to-1 license ratio] creating power dynamics between different players, it just creates instability in the supply chain,” he said. “And that’s not good for anyone in the supply chain. These price fluctuations, the existence of a persistent illicit market all create instability and chaos in the supply chain, which can potentially lead to some actors not paying other actors, for example.”

Among 750 small, independent cannabis businesses in a five-county region in Northern California who are members of Origins Council, a nonprofit that advocates on their behalf, roughly 85% are owed money, Executive Director Genine Coleman told CBT in late February. California’s supply chain is in the process of “collapsing” amidst a “real market access problem,” she said.

Those remarks come as Gov. Gavin Newsom’s office lauded on social media March 21 that state regulators increased illicit cannabis plant eradication by 1,274% in 2022. “We’re cracking down on the illicit cannabis market and ensuring our state maintains a safe, well-regulated, and legal marketplace that benefits Californians,” the governor’s office tweeted.

California's Department of Cannabis Control increased illegal cannabis plant eradication by 1,274% in 2022.

— Office of the Governor of California (@CAgovernor) March 21, 2023

We’re cracking down on the illicit cannabis market and ensuring our state maintains a safe, well-regulated, and legal marketplace that benefits Californians. pic.twitter.com/iJc0m59quU

But, without addressing the underlying causes of the illicit market, that eradication effort is only squeezing the balloon, Jain said.

A state’s legal cannabis industry’s success often depends on that supply chain stability. And even more so than focusing on law enforcement crackdowns, taxation or overregulation, California needs to address and prioritize its retail footprint before discussions of squashing the illicit market can truly hold value, Jain said.

The Retail Riddle

Local control.

That’s the main cause of California’s retail problem, Jain said.

“We often focus on challenges in the California market that are problematic but aren’t at the core of the problem or that aren’t at the heart of it,” he said. “So, the taxes are very problematic, for example. But really the challenging thing is we have set up a local [license] approval process that is impossible to navigate and that these local governments don’t have the resources themselves to administer.”

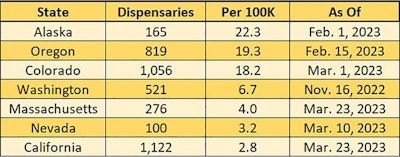

Despite a push by the state’s Department of Cannabis Control (DCC) to license more retailers since taking the regulatory steering wheel in July 2021, California’s current active licensee list equates to 2.8 storefront dispensaries per 100,000 people, the fewest among its legacy neighbors.

Oregon, for example, has 19.3 dispensaries per 100,000 people, according to February 2023 licensing data from the state’s Liquor and Cannabis Commission. Meanwhile, Colorado has 18.2 dispensaries per 100,000 people, as of March 1, according to licensing data from the state’s Marijuana Enforcement Division.

Among the seven states that launched adult-use cannabis sales in 2018 or earlier, California lags behind in active retail licenses per capita (shown below are dispensaries per 100,000 residents):

Aside from the numbers, it’s also important to take stock of where dispensaries are located within California, Jain said.

Currently, 10 cities combine for more than 500 dispensaries in California, representing nearly half of the state’s retail footprint, according to DCC licensing data.

Where to Do Business

Los Angeles has 244 dispensaries, while San Francisco has 68 active retail licenses. Sacramento has 35. Long Beach: 31. Those cities are among the best served with regard to cannabis retail.

Meanwhile, highly populated cities like Bakersfield, with a metro population of more than 900,000 people, prohibits retail altogether. Located in Kern County, the third largest area in the state with more than 8,100 square miles, Bakersfield is perhaps the best definition of a cannabis retail desert in the state in terms of location and number of people.

Anaheim, Irvine, Fremont, Santa Clarita, Fontana, Huntington Beach and Glendale are also among the 61% of cities and counties (327 of 539) that currently ban retail cannabis businesses, according to DCC.

In Huntington Beach, a city of roughly 200,000 people, voters passed Measure O, an ordinance that aims to put a 6% tax on cannabis retail sales, with a 55% majority in the November 2022 election.

“What’s frustrating about Huntington Beach is that even though voters resoundingly passed a cannabis tax measure in November 2022, the city council [changed political structure in the election], and now they intend to block a retail ordinance from passing,” Jain said. “A great example of how elected officials in California continue to ignore popular will on cannabis.”

In Fontana, a city of roughly 210,000 people in San Bernardino County, city council members passed an ordinance in July 2022 to allow three cannabis dispensaries, according to the Fontana Herald News. License applications are due March 30, but Jain said he fears it may take years before a Fontana dispensary opens in the regulated market. He bases that timeline on how similar ordinances have played out in Fresno, Oxnard and Costa Mesa, he said.

The Local Logjam

In Fresno, the fifth largest city in the state with more than 500,000 people and a metro population of more than 1 million people, city council members originally adopted an ordinance in 2019 to allow adult-use dispensaries in 2020, according to The Fresno Bee.

While Fresno has 10 dispensary licenses listed as active on DCC’s website, only two are open: Embarc and The Artist Tree, which cut their red ribbons last July, according to the Bee. That’s despite 19 businesses across the city receiving preliminary licenses more than a year ago, according to the news outlet.

Jain said he regularly spends five-plus hours per week tracking the state’s retail footprint, including what dispensaries licensed by the DCC are actually open and operational.

“And the scandalous thing is that it’s been almost four years, three and a half years to be exact, since [Fresno] passed the ordinance saying we want 21 dispensaries in this city,” Jain said. “And those stores are not open.”

Much of the same has played out in Oxnard, a city of more than 200,000 people where councilmembers began planning more than three years ago to license 16 dispensaries, according to the Ventura County Star. So far, those plans have led to two cannabis retail permits being issued, as of March 1, 2023, according to the city’s website. That local approval is despite 10 Oxnard businesses having state approval, according to DCC.

“Places like Oxnard, again, these are big cities of 200,000 people, where only one out of the 16 stores that were supposed to be open is actually open three to four years later,” Jain said. “And that’s why the legal market has plateaued.”

And in Costa Mesa, a city of roughly 110,00 people in Orange County, one dispensary has opened more than two years after voters passed Measure Q—to allow and tax cannabis retail—with a 65% majority in the 2020 election.

California’s local logjam is perhaps no more evident than here.

After 63 businesses submitted retail applications in 2021, Costa Mesa’s Development Services Department allocated 25% of its time and personnel resources toward reviewing and processing those applications, according to the Los Angeles Times’ Daily Pilot. As of February 2023, only 14 applicants had received their permits, and city council members authorized a refund of licensing and permitting fees for roughly 45 applicants, should they agree to voluntarily withdraw their requests after months of delay in the review process, according to the news outlet.

Costa Mesa’s Development Services Department has 51 employees, according to the city’s staff directory.

“[The city] had a 50-person agency processing these applications, and spent millions of dollars trying to review this highly bureaucratic application that was established, and they could only get through one-fifth of the applications,” Jain said. “And then the city recently threw up its hands and was like, ‘Oh well, we can’t do this. We don’t have the resources to do this. This is too much.’”

Despite state approval for 18 dispensary licenses in Costa Mesa, all but one aspiring business entrepreneur remain sidelined by the local backlog more than 27 months after voters passed Measure Q.

“There’s something almost antidemocratic going on where the machinery of government is preventing Californians from accessing legal cannabis, even though they have voted for it time and time and time again,” Jain said. “And it’s really remarkable.”

From Fontan to Fresno, Oxnard, Costa Mesa and elsewhere, local delays in approving businesses for entry into the industry have severely constricted retail growth in the state.

Beyond Storefront Access

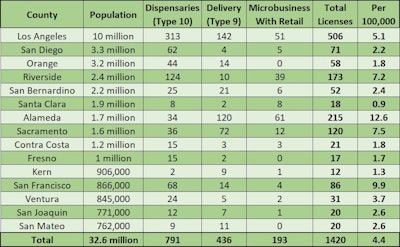

While storefront dispensaries represent a key indicator of consumer access to the regulated marketplace, California also has 500 active delivery licenses and 257 microbusiness licenses with retail activity, according to DCC licensing data as of March 23. Those license types combined with storefront dispensaries add up to 1,876 businesses with retail permits in the state.

So, what does that mean?

In San Diego County, which has four delivery and five microbusiness retail licensees, the additional license types don’t have much impact with 62 dispensaries already serving the 3.3 million people in the county.

But in Alameda County, which encompasses Oakland and Fremont, 120 delivery and 61 microbusiness retail licensees greatly increase access for roughly 1.7 million people who would otherwise be reliant upon 34 storefront dispensaries. The difference is 2 dispensaries per 100,000 people versus 12.6 licensees with retail services per 100,000 people.

Here’s a retail license snapshot of the 15 most populous counties in the state:

More Than a Decade Away

Still, the Achilles heel of California’s regulated cannabis market is also its opportunity: vast retail deserts like the city of Bakersfield, or Santa Clara and Kern counties—largely populated areas that remain unserved or underserved.

More specifically, Jain points to the slow rate at which new dispensaries are opening.

Among the roughly 1,050 open dispensaries in California, only some 400 are what Jain refers to as “new” stores. The other dispensaries were grandfathered in from California’s medical market, before adult-use sales began in January 2018.

In the 10 months after California streamlined three regulatory agencies into what is now the DCC, state regulators approved 140 storefront retail licenses, or 14 per month. Overall, California had 948 stores licensed as of May 9, 2022.

That rate increased slightly to roughly 17 storefront licenses per month getting approved at the state level since. Again, many of those licensees still need to navigate their local processes.

But for California’s retail market access to be more aligned with its legacy neighbors, the state would need roughly 4,000 dispensaries, or 10 stores per 100,000 people. At a rate of 15 new dispensaries opening per month, it would take more than a decade to get there.

Regardless, 15 new dispensary openings a month won’t bear much impact if they don’t land in the needed locations, Jain said.

So, what’s required? More advocacy at the local level? Does California need its state Legislature to step in?

“I would just put it this way—and this is the story that I wish was being told more in California—cannabis local control as we know now is at odds with all of the values that we say that we care about in California,” Jain said. “We can no longer allow people to sort of trumpet their belief in social equity and environmental protection and in cannabis as medicine, and then to be indifferent to the fact that local governments across California are obstructing the will of California.”