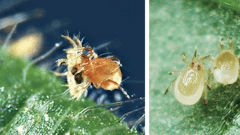

Biological control is a preventative approach used to manage insect and/or mite pests through the use of natural predators and parasitoids. A number of factors can cause a biological control program to fail to provide sufficient regulation of insect and mite pests. Here are four of the most common factors to avoid so you can get the most from your parasitoids and predators.

1. Not implementing an ‘aggressive’ scouting program

Because biological control is a preventative approach, it is important to develop and implement an aggressive scouting/monitoring program that will allow you to determine the population dynamics (relationship between pest populations and environmental factors that can influence populations) and track trends in pest numbers during the growing season. Scouting at least twice per week will result in more efficient timing of natural enemy releases. However, before releasing parasitoids, remove any yellow sticky cards at least one week prior, as adult parasitoids are attracted to and will be captured on the yellow sticky cards.

2. Not conducting a quality assessment of purchased natural enemies

Quality assessment and functional natural enemies that are capable of locating and killing targeted hosts are critical to a biological control program’s success. Shipments of natural enemies (parasitoids and/or predators) should be stored for no more than three days to avoid negatively affecting fitness and foraging ability, which can impact the performance of natural enemies in regulating pest populations. In most cases, natural enemies should be released immediately upon receipt.

Before release, however, always check to ensure that natural enemies are alive. For predatory mites such as Phytoseiulus persimilis, which are shipped in vermiculite or bran carriers, a small amount of the carrier can be placed on a white sheet of paper and checked with a 10x hand lens or a dissecting microscope to determine if the predatory mites are active or not. Parasitoids, such as Encarsia formosa and Eretmocerus eremicus, shipped as parasitized pupae or mummied aphids can be evaluated for quality by placing a sample release card (for whitefly parasitoids) or small sample of the carrier with mummified aphids (for aphid parasitoids) inside a glass Mason jar with a lid. Affix a 1-inch section of a yellow sticky card to the bottom of the lid. Check the Mason jar regularly to ensure that adults are emerging from the pupae or mummified aphids. The number of potential functional parasitoids that emerged from pupae or mummified aphids can be assessed after all the parasitoids have died in the Mason jar.

3. Not releasing enough natural enemies

Do not be “cheap” when purchasing natural enemies. Always release a sufficient number to ensure regulation of existing insect and/or mite pest populations. Not releasing enough natural enemies will likely result in poor regulation of pest populations and subsequent damage to a cannabis crop. Be sure to consult supplier/distributor catalogs for specific information regarding release rates of natural enemies.

4. Releasing natural enemies too late

Biological control is a preventative approach and, as such, natural enemies are typically released before insect and/or mite pest populations are even detected to make sure pest populations do not become established. Therefore, order natural enemies in advance so that you receive shipments at least every other week, which will ensure that you receive a consistent shipment of natural enemies early in the production cycle. Once the cannabis crop starts budding and producing the sticky trichomes, it is too late to release any natural enemies.