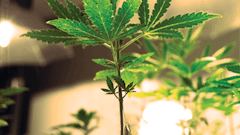

Broad mites, russet mites, spider mites, aphids, whiteflies, fungus gnats and powdery mildew are just a few of the threats for cannabis plants and cultivation facilities, be it indoor, outdoor or a greenhouse. As many cannabis pests as there are, there are about just as many potential infection/contamination sources.

Here are some primary sources of contamination:

- Home gardens. Some employees may have home grows (i.e., they grow cannabis and other crops in gardens at home). If said grow/garden is contaminated, it is possible to bring that contaminant to other locations, including that employee’s workplace. Some cannabis companies have put policies in place banning employees from participating in home cultivation. While this policy does indeed protect the business’s crop from home garden contamination, employers risk alienating talented, passionate prospective employees. Companies considering implementing these policies must weigh them carefully.

- Unsterilized materials/supplies. Even if a product leaves the manufacturer’s facility in sterile condition, it can become compromised in shipping or by a distributor. For example, improperly storing soil or growing media in unsatisfactory conditions (e.g., a warm and wet/damp environment, near high traffic areas or near other plant matter), can lead to that medium getting infected. Always make sure you have a sterilized media/soil source by testing them in-house or with a trusted third-party lab.

- Poor air intake filtration. For indoor and greenhouse facilities, there is a multitude of air filtration options. Greenhouses often utilize specific-sized bug screens on their air intake systems/vents, while most indoor facilities incorporate air filtration capabilities into their HVAC systems (including, but not limited to, UV light filters to kill powdery mildew spores). Failure to address air filtration in either facility is simply asking for problems. If a cultivation operation is not filtering incoming air, it’s not a question of “if” a facility will become contaminated, but “when” it will become contaminated.

- Vegetation/crops surrounding a facility. Many indoor facilities and greenhouses containing cannabis or other crops have been infected by pests or diseases that were present on crops or vegetation that surrounded that operation. Cannabis cultivators should periodically inspect all surrounding trees, shrubs, and/or weeds, as well as any neighboring crops, for pests and disease.

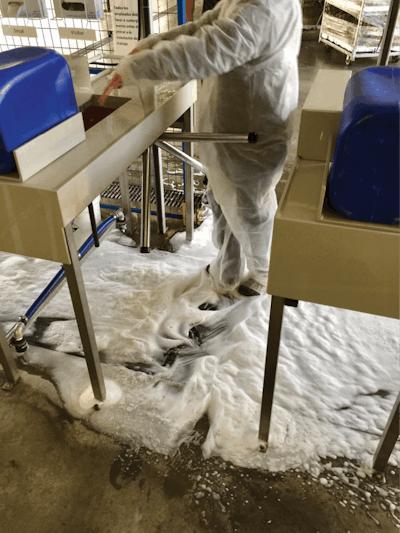

- Employee clothes/shoes. Insects and mold spores can hitch rides on your employees’ clothes, even in the time it takes for them to get from their parked car to the facility. Growers should set up decontamination protocols for all employees each time they enter the greenhouse or facility. Preferably all employees change clothes and shoes before entering a facility. Growers also can provide sanitizing foot bath floor mats at all doors, and/or disinfecting foam containing hydrogen peroxide at the entrance of a greenhouse. An employee decontamination chamber is also advisable for both indoor and greenhouse operations. To prevent the threat of infection by hand, all employees must wash or sanitize their hands prior to entering the facility, as well.

- Clones/new genetics. In my experience, the No. 1 source of pest and disease in a cannabis cultivation facility is from new clones, especially those introduced during the pursuit of new genetics/cultivars. It is much less time-consuming to start a given cultivar via a clone of a preferred genotype that expresses preferred phenotypes than it is to start from seed. With seeds, growers must search for desirable traits and perform a “pheno-hunt,” a search for a phenotype from which to take clones to begin production. While easier to manage than seeds, sometimes those clones are indeed contaminated with a pest or disease (or multiples of both). All clones should be properly quarantined and guaranteed to be pest- and disease-free prior to introducing it to any production area. Preferably, new clones should be kept off-site (this discourages employees from checking in on new clones before moving to other production areas). At minimum, they should be held in a separate, contained space for at least one month. Assign dedicated employees who will inspect the new clones for signs of pests, disease or nutrient deficiencies, then have those employees sanitize themselves or change their clothing before moving on to production areas.

Regarding neighboring farm crops, one must always be aware of how and when an infected neighbor/farmer uses preventative applications or treats their infected crops, as well, as those pesticides or harmful chemicals can affect your cannabis cultivation facility. Plan for the event and take necessary action such as closing ventilation openings and turning off any ventilation fans to prevent the intake of any potentially harmful chemicals. For instance, some Central Valley California greenhouses are in agriculture zones where airplanes crop dust large tracts of acreage. The potential for chemical drift is possible; therefore, it is best to know when a neighbor is planning any application of chemicals that could be harmful to cannabis plants or the humans consuming it.

A Closer Look At Clones

Typical past behavior has been to obtain a given desired cultivar in clone form and, after quarantine, to deem the clone a “mother,” meaning that the original clone is grown to maturity in order to produce more clones. Those clones could be grown to produce more clones (by turning them into mother plants), or simply utilized for production.

This has been the most common way cannabis growers have propagated crops for the past two decades (not counting autoflowering plants or feminized seeds). This system, unfortunately, led to what we now consider reckless behaviors and practices.

About 20 or so years ago, I started noticing anomalies and unusual signs and symptoms on cannabis plants in multiple facilities in multiple states, starting in California. The symptoms were multiple: leaves curved sideways, with some showing discoloration as if it had been painted a faint yellow. Along with other strange deformities in new young growth, at its extreme, symptoms included diminished yields of up to 50% in combination with a major drop in both potency (THC content) and aromatic qualities (terpene content).

After seeing these unexplained symptoms multiple times, I brought the observations up with one of my mentors, Robert C. Clarke, to see if he had heard of any disease or virus that would cause what I was observing. (Editor’s note: Clarke, co-founder of BioAgronomics Group, is a regular contributor to CBT and is featured in this issue.) He explained it could very well be a virus or another form of viroid contamination, but that there were no test kits available to positively identify the infection other than in a university setting, which was impossible at the time because the infected tissue was cannabis. But Clarke surmised the infection was either a virus or viroid and that possibly one could eliminate the infection via meristematic tissue culture—essentially taking a few cells from the newest plant material that had yet to be contaminated by the virus from which to propagate infection-free plants. Meristem tissue culture was a common practice in many other markets, including produce such as berries, but few if any cannabis growers used this process at the start of the millennium.

How a California Problem Became (Inter)National

During the next 20 years, I continued to see the same symptoms in various gardens in multiple states but could never confirm what it was. I heard it hypostatized as hemp streak virus, then Sunn-hemp mosaic virus, but none of these were ever confirmed in any way. I’ve heard others describe their experiences dealing with similar symptoms as a broad mite infection to “genetic drift,” neither of which are correct.

Then a few years ago I heard a term utilized to describe the symptoms I had been witnessing for years: “dudders disease” or “dudding disease.” While the terms did pick up in popularity, I’ve always had issues with them—I believed that whatever was causing these symptoms was not new, that it already had a name, and, as such, didn’t need a new one.

While only a brave few would risk admitting it, in 2015, there were thousands of potentially virus- or viroid-infected clones being shipped to every emerging legal cannabis market in the U.S. from California—this is how a California-focused problem became a national one. If infected clones entered new legal markets, it could ultimately lead to the loss of many cultivars and create quality issues in those new markets. All because it was easier to have California clones sent eastbound than starting from seed.

The problem even crossed international borders.

In Canada, licensed production facilities had a given amount of time to obtain desired genetics, which they had to declare to the government. During the window of opportunity, some Canadian groups chose to obtain the most desirable genetics in the form of seeds and clones from the U.S. With those clones came the possibilities of viral infection. That may have been a blessing in disguise, however, as federal legalization in Canada opened the door to this infection being studied by government officials, university researchers, and private research labs (although little published research has been done on the viroid in cannabis).

In recent conversations with a friend who is part owner of a Canadian tissue culture company, I learned that some of the U.S.-born clones did indeed contain a viroid of some form or another, and that Canadian researchers were able to confirm the identity (although they were not the first) of the root cause of the symptoms I’ve been seeing for two decades: hop latent viroid, or HpLVd.

He also shared that, to prevent the possibilities of contamination caused by clones from the U.S., some Canadian cannabis producers chose to import seeds from America and other countries. I also learned that HpLVd is transmittable from parent plant to the seed it produces: if the mother is infected, so is the seed. (Canadian researchers traced HpLVd back to imported seeds.)

The most likely explanation for how the virus propagates is from the current cloning practices that have been employed for decades. When a clone is cut off the parent plant, the potential exists to contaminate the clone with a virus on the surface of the branch. When the cut was made, the virus was introduced to the cutting’s inner tissue.

Because the plant itself can become its own vector for disease, and because mother plants are especially at risk for viral contamination as the plant’s immune system gets weaker over time, infections generally can only be treated by destroying the crop, the mother plants and any clones and seed taken from those mother plants, and then starting from scratch.

That is unless growers can leverage meristematic tissue culture to save their genetics, something that Clarke had proposed years ago: meristematic tissue culture can rid the plant of certain viruses. (Not unrelatedly, tissue culture is also a great way to preserve a given cultivar for later use, or for storing useful male specimens for use in breeding projects. A cultivator could literally store 5,000 cultivar specimens in a relatively small area with a fairly low maintenance cost compared to upkeeping mother plants from which to clone, costs compounded by the potential risks associated with those clonal methods.)

The practice of cloning from a host mother is potentially problematic, and that tissue culture of cannabis for mass production is the only viable answer when one considers the risks of introducing a viral contamination by using clones and/or seed.

All of this to say: When considering disease vectors, cannabis cultivators also should look at their long-held belief and practices with an objective lens. Only unbiased evaluation should decide whether current practices put their crop, and their business, at risk.