Editor’s note: This is Part I of a three-part series that follows Buckeye Relief, a 25,000-square-foot indoor cultivation facility in Eastlake, Ohio, from its license application and buildout through its first harvest.

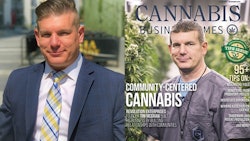

Andy Rayburn, Buckeye Relief’s co-founder and CEO, has a familiar cannabis story: About four years ago, a friend battling late-stage cancer called Rayburn to recount his first medical cannabis experience from the night before. For the first time in two years, he slept through the night and woke up refreshed.

“I was very moved by that,” Rayburn says.

What makes Rayburn’s cannabis story different from many is that he was able to act upon his emotional response. Having sold his first company (an industrial distribution company that he grew from 20 employees in two cities to 385 employees in 13 cities) in 2000, Rayburn possessed the business acumen and capital to launch himself into the cannabis industry. (Rayburn is also a part-owner of the Cleveland Cavaliers NBA franchise.)

Rayburn saw his opportunity in 2016 when the state legislature was looking to legalize medical cannabis. He partnered with longtime friend Scott Halloran, now Buckeye Relief’s chief operating officer (COO), to create the company in early 2016. On June 8 of that year, Ohio Gov. John Kasich signed into law the medical cannabis bill, and Rayburn was ready to find his place in the Buckeye State’s new medical program.

Head Start

Rayburn and Halloran’s first task in launching a cannabis cultivation company was to learn what others were doing. “The first thing I did, with Scott alongside, was start to put together pieces of a team that would … give us a victory on our application,” the CEO says.

The duo spent the first half of 2016 traveling the country, visiting multiple operators in various states (including Colorado and California) that had legalized cannabis and also meeting with different consultants, legal experts, contractors and manufacturers.

“We wanted people that were experienced in the cannabis industry, experienced in multiple states’ application processes,” Rayburn explains, “but not tied down to traditional operating approaches from the cannabis industry. In other words, people that were open to … new technologies and new ideas about how to operate a cannabis business.”

Buckeye selected Denver-based law firm Vicente Sederberg to coordinate the application process. During the application writing phase, “we didn’t focus so much on cultivation techniques and that kind of stuff. That’s what our consultants did,” Halloran says. Instead, “we spent a fair bit of time finding our location.”

Rayburn and Halloran visited more than 20 towns in their quest to find a home for Buckeye Relief, all of them in or around Northeast Ohio. “We wanted to be able to run a business that was close enough to our homes and community and neighborhoods that we knew,” Halloran says.

Eastlake, a small town less than 20 miles from downtown Cleveland, was one of the few communities that seemed open to Buckeye building its home there. “Once they understood the business that we were going to be bringing to the city, they couldn’t have been more supportive,” Halloran says. Rayburn and Halloran started developing strong ties to Eastlake, meeting with the mayor and his staff, the city council, the police chief and concerned residents.

Those efforts paid dividends when the co-founders discovered Buckeye’s original site location was not going to work due to wetland restrictions. As a solution, the city offered Buckeye a 10-acre parcel of land that had gone unused for more than 20 years. In a demonstration of good faith to the community, Buckeye purchased the property at the full-appraised value.

Next, the team secured engineer-approved architectural drawings, even before it had submitted its application to state evaluators. Having approved architectural drawings and starting on-site preparation were obvious risks for the co-founders, but those risks were calculated.

“We showed [the state] … we already had approved drawings. We had a maximum price bid from our contractor. We showed an escrow account with that amount of money in it so that we could tell the story to the state, ‘If you give us a license, we’re ready to start building the very next day,” Halloran explains.

On Nov. 30, 2017, Buckeye received the news: It scored top marks for a cultivator application from the state of Ohio, 179.28 out of a possible 200 points. Rayburn congratulated his team, popped a bottle of Dom Pérignon and kept his company’s promise to the state by beginning construction the following day.

Ice-Breaking

Breaking ground in the winter is rarely an easy feat. Buckeye’s task was made more difficult by freezes and quick thaws that left the ground either unworkable or soggy. “We ended up having to spend a fairly good-size, six-figure [sum thawing] and then scraping out the [area for] the building a couple of times, sort of to de-muck it, just so that we [could] pour our foundation,” Halloran says.

Buckeye relied once again on good relationships, this time with its contractors, to work through those issues. “They didn’t miss a minute of time, no matter how cold or miserable it was here through December, January, February,” Rayburn says. In fact, the local union workers Buckeye hired worked overtime to keep the project on schedule.

Team Building

Buckeye made its first major cultivation hires in February 2018. Jeremy Shechter, Buckeye’s cultivation technology director, joined the team on the ground floor, so to speak. “We were two months into construction at that point [in February 2018]. … The outside frame was up, and it wasn’t until about three weeks [after] I started that we even had a floor,” he says.

Matt Kispert, Buckeye’s cultivation director, joined the team in May 2018. “They were putting up the drywall,” by the time he joined, Kispert says.

Shechter and Kispert fit Rayburn’s ideal-employee mold. As a former aquaponics manager at FarmTek, Shechter had experience working with traditional and cannabis crops as well as aquaponics and hydroponics. He also holds a degree in food, agricultural and biological engineering from Ohio State University. Kispert was a greenhouse manager and consultant for CropKing, an Ohio-based greenhouse manufacturing company. Previously, he worked with Shechter at FarmTek, also as a consultant, advising on cannabis and traditional grow operations.

Both men were given the same initial task—review the plan in Buckeye’s application and ensure that it made logical and agronomical sense. “During the application phase, our consultants put together a pretty good, high-level view of what they first [imagined things] … to be like,” Shechter says. “Like the racking and the lighting and the irrigation and the water room.”

Shechter’s next task was to turn those high-level plans into reality. For example, in the water room, the application consultants “basically just wanted to see some kind of dosing machine, an RO [reverse osmosis] system and some storage tanks” without any further specifications, he says. “And I kind of just ran with that.”

However, not everything translates well from theory to practice. Case in point: Buckeye’s initial plan to recirculate and filter leachate. “Originally we hoped to capture our runoff … from our fertigation, and then clean it and reuse it. The issue [is that] all of our leachate goes into floor drains,” Halloran says. Those floor drains collect everything from nutrient runoff [to] spills and pesticides (all allowed by the state and used as a last resort, says Halloran), and that mix is difficult to purify. Any misfire in the purification process could leave nutrient solution or pesticides in the recirculated water and place plants at risk.

This shift toward a drain-to-waste system doesn’t preclude the company from returning to its original plan, should it find a way of ensuring clean water. All necessary plumbing for a recirculation system is already installed. “The hardware’s there; the drains all go to a sump, and we have the capabilities of pumping out of that sump into whatever sort of future filtration system we are to install to re-utilize that water,” Kispert says. Shechter adds that having “a straight drain-to-waste system kind of simplifies the operations in a time where there’s a lot going on” during construction.

Resource conservation remains a priority at Buckeye, though. The Buckeye team decided that since it wasn’t going to recirculate waste-water, it could recapture the condensate from its HVAC units. “At full capacity, we will be using around 10,000 gallons of water a day,” Halloran says, “but recapturing around 6,000 of that out of the air, cleaning it and recirculating it.”

The CO2 system also had to be redesigned from the original plan. “We had initially planned for a self-generating CO2 system, but we decided to go with a more conventional CO2 bulk-tank distribution manifold system that’s directly injected into our HVAC system,” Shechter says. “It was just something that was much simpler, cost effective, [and] worry free.”

Most of the deviations were minor in the grand scheme of things, Rayburn says. “Because of all that early planning, the construction process was really as smooth as a construction could be.”

Flower Ready

The Buckeye team’s goal was to begin planting seeds by Aug. 1. However, in May, many cultivation rooms remained under construction. The nursery, for instance, was mostly bare when Kispert joined the team. “I actually personally wound up building most of the stuff in the nursery,” he says.

Because of his prior relationship with CropKing, Kispert decided to use his former employer’s vertical racks and fertigation system for Buckeye’s upstart plants. The fertigation system is called a fertroller, which is “like a peristaltic-based nutrient delivery system that does all the watering, fertilizer [and] dosing,” Kispert says.

Ridder environmental control systems (ECS) control the rest of the cultivation areas. Buckeye chose Ridder for a variety of reasons: The ECS company was the friendliest during talks, its system was the most customizable, in Shechter's view, and its North America headquarters is 30 minutes from Buckeye’s facility, enabling Ridder to send techs rapidly should problems arise, Shechter says.

One design aspect that didn’t change was the mineral salt fertilizer system. Using a hydroponic mineral salt system allows Buckeye to dial in milligrams of nutrients per liter of water. That, in combination with a rockwool growing media, gives Buckeye full control of the fertigation process, Shechter says. “Rockwool doesn’t really have any kind of ion exchange capacity. It’s kind of a total inert blank slate.”

Working with a hydroponic system in an indoor cultivation environment leaves little room for error. “It’s a wonderful thing that we’re controlling everything that the plant gets,” Shechter says. “But it’s also a scary thing ... because if a piece of equipment goes out, like the lighting or the HVAC units or the CO2 or the irrigation, and it doesn’t receive that part of the pie, then the plants can really suffer for it.”

To avoid catastrophe (such as losing an entire flower room to a mechanical issue), Buckeye integrated an alarm into its ECS. The ECS knows the amount of CO2, water and nutrients that need to be pumped into each room and flower bed. If one aspect of the system fails, like a plugged emitter or a closed valve, and the computer can’t disperse the needed nutrient, the cultivation team receives a notification on their computers and mobile devices. “You just cannot run an indoor grow without a sophisticated alarm package or you’re asking for a lot of issues,” Shechter says.

The watering system also has a redundancy: a duplex pumping system. If one pump burns out, the other can keep water circulating while the team fixes or replaces the defective pump.

Rayburn spared no expense in designing and building his facility. “If there was an option that would allow us to grow better, higher-quality plants—for example … a new system to control rooms … or a new lighting option, a new rack option—we went for the highest technology, the most efficient equipment that we could get,” Rayburn says.

“We weren’t looking at this as an investment” with a quick return, Halloran says. “We were looking at this as a business.”

That time, energy and financial investment allowed Buckeye Relief’s team to finish construction one day ahead of schedule and plant its first seeds July 30, 2018.