“Hi, Jim. We’re going to publish your article in two parts. What name do you want to use?”

It’s 1971, and James Goodwin is standing in his New York City apartment–eyeing the Colombian Gold plants carpeting one of the bedroom floors–weighing the question from the publisher of Rolling Stone magazine. The popular publication was getting ready to print Goodwin’s first-ever writing on cannabis cultivation in its New York City Flyer (how to grow high-quality cannabis in your New York apartment) and was calling to check on his byline preference.

The question comes out of the blue for Goodwin, who forgot he submitted an article months earlier after being spurred by a journalist friend of his to do so. The Controlled Substances Act had just become law, so using his real name is out of the question.

Goodwin looks down at his cats circling his feet: Frank and Mellon. “Frank Mellon …” he thinks, quickly shaking off the idea as sounding too familiar.

After some hesitation, he finally responds in his New England accent, “Make it Mel Frank.”

The rest, as they say, is cannabis history.

In the Navy Now

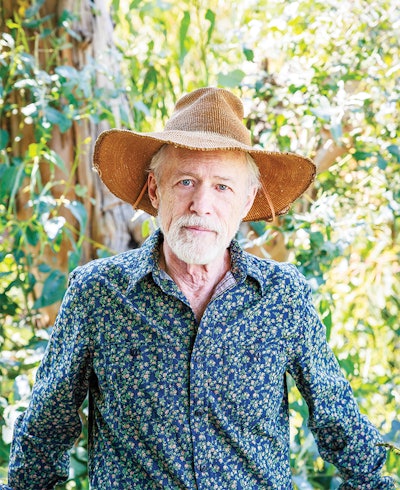

That innocuous phone call birthed a name that has become synonymous with cannabis cultivation and the industry’s culture. Mel Frank has been an author, a photographer, a publisher (Red Eye Press), a seed keeper, a breeder and a grower, among other things.

Born in 1944 as the second-oldest child and only son of four siblings to a family in Lynn, a city just north of Boston, Frank’s life could have taken a much different turn had it not been for some serendipity, risk-taking, and the keen eye of the manager of the grocery store where he worked in the meat department.

Frank started his butcher career at 14 to help support his family, as his father was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, most commonly referred to as ALS. “That’s … pretty ugly,” Frank says. “When he started to really deteriorate and was unable to work, I was a sophomore in a regular public high school.” At a family meeting—a common occurrence in the Goodwin household—it was decided that there “wouldn’t be any money for me to go to college. I’d have to do that on my own.”

Nixing college plans, Frank decided to transfer to a trade school to study to be an electrician. “But when I turned 16, I got hired at a newly built supermarket in the meat department ... that paid much more than working as a rookie electrician.” So he stayed at that job, and one night, with his car in the shop, the store manager gave the newly minted 19-year-old Frank a ride back home.

“While we were driving, he’s talking to me and he said, ‘Do you remember a couple of nights ago when these guys came in at closing time in their suits?’” Frank did remember them, as they had spent an odd amount of time chatting with him. “‘They were executives from the company,’ he said, ‘and they have plans for you.’”

His manager then laid out what the next few years of Frank’s life would look like as he was essentially being trained to become a manager himself. Frank recalls his manager telling him, “You gotta think about this: Is this what you want to do with your life?”

“[‘The Marijuana Grower’s Guide Deluxe’] educated an entire generation of growers. Without [Frank] and a couple of others that wrote early treatises on indoor cultivation, it would’ve taken a lot longer for the industry to get where it is.” David Holmes, owner of Clade9

Weighing his options, Frank joined the Navy.

“I didn’t have any plans for my life,” he explains, noting the military draft meant he would likely be conscripted should he choose not to enlist. “I didn’t want to go in the Army, and the Navy had food and travel. I wanted to travel at least, so that’s what I did.”

His trade school education got him a post as an electronics technician right out of bootcamp.

He traveled the world with the Navy for three years before the ship docked at a Bethlehem Steel shipyard near Baltimore, needing a massive upgrade. While docked, the ship required a skeleton crew to remain on duty or the vessel would be decommissioned. He was the representative of the Operations department selected to stay with the ship along with seven other crew members and an officer.

Their only real task was to pick up the mail addressed to the ship every day and distribute it to the other 220 transferred crew members.

Most days were spent sitting around “reading all these magazines and local newspapers,” Frank says. “And in the summer of 1967, they’re all writing about kids going blind because they took acid and looked at the sun, and how this guy smoked marijuana and jumped off a building. It was all about these horrible things happening. All these college kids and young kids who were doing marijuana and acid, and I’m thinking, ‘I can’t wait to get outta here and try some of this stuff!’”

The Big Apple

Nine months after his ship docked at the steel yard, Frank completed his service and returned home to Lynn to spend the next two months helping his mother around the house.

Frank then moved to New York City where he found a seven-room sublet on the Upper West Side at just $125 per month. His girlfriend and her best friend later moved in with him. During the 1967 Christmas holidays, the best friend’s brother introduced Frank to cannabis and taught him to roll a joint. “It was Mexican pot, mostly seeds and stems,” Frank says.

Frank had already filled his apartment with houseplants, and some were small flowering plants grown under fluorescents. In the spring of 1968, he decided to try growing his first cannabis seeds in a small 8-foot-by-8-foot room. “I only knew that it was hemp, a field crop, so I sectioned a corner of the room with boards, put down a plastic sheet, and filled it with about 6 or 8 inches of Swiss Farms topsoil, chicken manure, and sand from a construction site, and then set up a few four-foot fluorescent lights that I could raise and lower,” he details. And that’s how Frank began working out the intricacies of indoor cannabis cultivation.

Like many cultivators who hop down the cannabis rabbit hole, Frank was hooked. It wasn’t long before he was purchasing different Gro-Lux lights to see how his cannabis plants would react to the varying spectral outputs. When he found some white, hardware-store fluorescents yielded better results than early horticultural lighting lamps, he viewed it as part of the scientific discovery process. He learned from his first crop that it was better to use movable pots, and that shorter daylengths were necessary for flowering.

Frank never sold what he grew (whether flower or seed), part of the reason he never attracted serious attention from the law, he believes. He gave the fruits of his labor away, a practice he continues today.

By coincidence, when Frank submitted his article to Rolling Stone, another cannabis cultivation-related submission came from Ed Rosenthal, another now well-known author of cannabis growing guides. “Ed’s article was about his efforts to sell growing kits that he would set up for you with 4-inch pots and fluorescents,” Frank recalls. The Rolling Stone publisher gave Rosenthal Frank’s contact information “and within 5 minutes of meeting, Ed said, ‘We should write a book together.’ … Ed was very persistent, and after a few months I finally relented. We basically took my two-part article, revised that from being New York centric, added some about outdoor growing, and Ed moved to California, looking for a publisher.

“Ed eventually found publisher Level Press of San Francisco. Three years after he left New York, he came back with a copy of our ‘Indoor/Outdoor Highest-Quality Marijuana Grower’s Guide.’ We each made 17.5 cents per sale, and we didn’t choose that title,” Frank remembers with a laugh.

Between writing the manuscript and seeing the published book, Frank took night courses at the City College of New York (CCNY), studying biology. That education showed him in retrospect just how much better “Marijuana Grower’s Guide” could be. “When I looked at it [in 1974], I was really embarrassed,” Frank says. “I was in my junior year of college, I had a lot of biology, especially botany and microbiology and had also grown five more crops since writing the article, and I said to myself, ‘When I finish college, I’m going to write the best book I can.’ And I started to seriously research what was published on cannabis.”

Frank spent the next three years using a pocketful of nickels at libraries in New York, Mississippi and California to photocopy any articles and research papers he could find on cannabis and hemp. After graduating from CCNY, he broadened the range of his research by moving to San Francisco in the spring of 1976.

“I would just go through the Dewey Decimal system, looking for anything that related to cannabis, hemp, THC, marijuana, and so forth,” he says. “And I would just copy them and then bring them home to study. I think I got close to 400 [sources], which I was surprised by. Almost all of them were really useless for growing info. But I was starting to understand the chemistry and got almost nothing on growing. There was an early 1893 paper on growing hemp, and another one—maybe [circa] 1913—and they really didn’t tell me anything.”

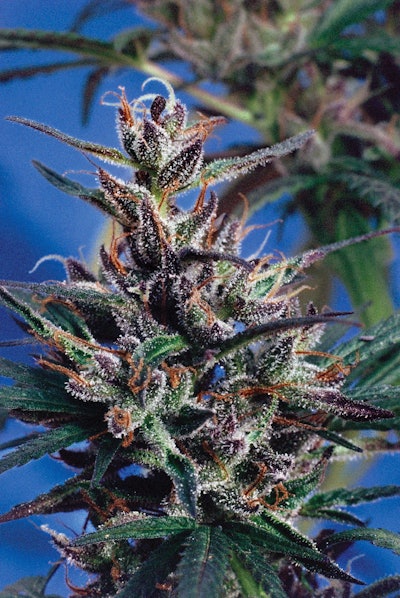

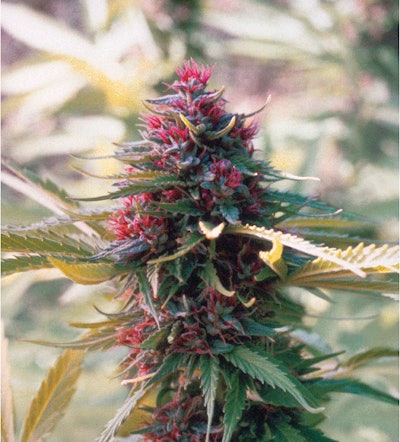

While writing the new edition, “Marijuana Grower’s Guide Deluxe,” he soon realized there were very few photographs of growing cannabis to illustrate his writing. “So I bought an Olympus OM1 and began photographing my own plants and any outdoor plants I learned of. My artist sister, Ellen Laincz, drew the maps and charts, and a former roommate, Oliver Williams did the drawings, so all of their good work added to the professional look of the book.

“I also wanted to take photomicrographs to show people the resin glands and also the degradation of the resin glands,” Frank adds. “I met a guy who was photographing slices of moon rocks through a microscope, and he offered to sell me an older light microscope. I began tinkering with ways to take photomicrographs without having the colors washed out, and found I could use sunlight to illuminate the resin glands on top of colored paper, rather than being illuminated from below.”

Collecting those images, more than 200 research citations and years of personal cultivation experience, Frank and Rosenthal’s most influential work, “Marijuana Grower’s Guide Deluxe,” was published by And/Or Press in 1978.

Going Deluxe

The impact of “Deluxe” on the cannabis industry cannot be overstated. Countless growers active in today’s regulated markets point to that book as their introduction to the world of cannabis cultivation.

“It educated an entire generation of growers,” says David Holmes, owner of Clade9. “Without him and a couple of others who wrote early treatises on indoor cultivation, it would’ve taken a lot longer for the industry to get where it is.”

“The impact [of ‘Deluxe’] was huge,” adds BioAgronomics Group co-founder Robert C. Clarke (another cannabis industry legend in his own right and a regular columnist in CBT). “It was the first book that really explained how to do it. Bill Drake … put together a lot of information, but it didn’t go into how you really grow dope. It was, ‘How do you rear a nice, healthy cannabis plant?’”

Clarke says “Deluxe” went beyond his own seminal work, “Marijuana Botany,” which covered basic theory about cannabis plants. The book’s success even helped Clarke get his work printed through the same publisher, he says. It was the spark of a fruitful relationship between two minds.

“Deluxe’s” popularity was in part due to the mainstream attraction it garnered. “The most satisfying thing after writing the book was that The New York Times reviewed the book,” Frank says, boasting how the reviewer called the book “as accessible a study of a single plant, at this high level of seriousness, as one is likely to find.”

“Why that struck me so much is because that was my whole thing: I was trying to make all of it accessible to people who weren’t scientifically trained,” Frank says. After the Times review, bookstores began to order it, greatly increasing the book’s availability to the general public.

Sharing Seeds

“Deluxe” not only brought Frank and Rosenthal notoriety in the cannabis industry but also an avalanche of outreach from other early cannabis pioneers. Frank was soon introduced to Clarke by David Watson (aka Skunkman Sam) in 1978, not long after “Deluxe” was published, and the trio have been good friends ever since.

Watson and Clarke were based in Santa Cruz, while Frank and Rosenthal lived together in a house in Oakland. Frank and Rosenthal converted a shed located in their backyard into an inconspicuous makeshift greenhouse in which Frank would grow various varieties—mostly landraces—that Rosenthal and many others would bring him. In their first meeting, Clarke felt an immediate kinship with Frank, whom he refers to by his birth name.

“Jim has always been a scientist, you know, and so am I,” Clarke says. (Frank edited and published the second edition of Clarke’s “HASHISH!” in 2010.)

As “Deluxe’s” popularity grew, so did Frank’s seed collection. “After ‘Deluxe’ came out, people just started visiting me. These were guys who would go on the Hippie Hashish Trail, and they would collect seeds,” Frank says, referring to the well-known “Hippie Trail” where growers from the U.S. and Europe would hike through Lebanon, Afghanistan and into India in search of cannabis seeds. “So they’d visit with their Afghani seeds that they brought back, and they’d trade me some for varieties I had. So that was great. That’s where I got almost all the stock I had.”

Rosenthal, a frequent visitor of Amsterdam’s coffee shops, one day brought back seeds called “Durban Poison” from a South African coffee shop. After growing his first crop of that new variety, Frank quickly saw how different this plant was from the landraces he was used to working with.

“The earliness of it was really incredible,” Frank says, remembering how Durban Poison would finish by mid-September rather than mid-October to December like other tropical landraces. “So, I did a lot of breeding with Durban because I knew for colder areas back east and the Great Lakes areas, those people needed this [early flowering] stuff.” Crossing Durban and Afghani 1 his Congolese and Nigerian landraces yielded potent tropical plants that would mature much earlier.

While he did not create or discover Durban Poison, its popularity in North American cannabis is often noted as a direct result of his breeding work with the genetic, Holmes says. “That work he did on the breeding of Durban Poison made it more accessible and made it a really popular strain for many years.” It has remained one of the most widely grown strains in the regulated market.

At its peak in 1982, Frank’s seed collection stretched to more than 200 mostly landraces, until a series of unfortunate events led to its entire loss. A fire on a neighboring property forced emergency crews to get access to his home, where firefighters discovered the greenhouse’s contents.

“Nobody was home, and when I did come home, the fire engines were just leaving. The street was wet, a bunch of people from the neighborhood were out there and they all said, ‘Wow, you were growing a lot of pot back there. They kept bringing out bagful after bagful of pot.’”

Fearing a police raid, Frank took his seed collection stored in film canisters and asked a neighbor to hide the collection under his bed until the risk passed. Unfortunately for Frank, his neighbor moved the collection from his bedroom to his attic. The Oakland summer heat essentially cooked the seeds, “so I couldn’t get a single seed to pop,” Frank laments. “My heart breaks now.”

Frank still has the detailed record of those lost seeds, written in 1983. Looking down at his record, he lists the collection, reciting numbers and origins: 60 Colombian, 26 Mexican, 24 Indian, 23 Thais, 17 mostly hybrids from Hawaii, 14 Kush,13 Afghani, four from Pakistan and Panama, three each from Congo, Indonesia, and Jamaica, three hemps, two each from China, Nepal and Nigeria, one each from Cambodia, Myanmar, Kenya, Korea, and one landrace each from Tibet, Durban, Lesotho, Transkei, Swaziland, Sumatra, and Zaire. “I almost cried,” Frank says.

While the loss of his genetic collection was devastating, plants sprouted from the seeds he lost were, at the very least, preserved in those he donated and in his photographs. Frank continued to write articles in High Times, and, in 1988, he wrote and published “Marijuana Grower’s Insider’s Guide,” as a reaction to the Drug Enforcement Agency’s concentrating on eliminating outdoor grows, particularly in California. “Growing was moving indoors, and the ‘Insider’s Guide’ addressed that,” Frank says.

He also continued to take photographs—mostly of outdoor farms and growers with their faces obscured (for obvious reasons). Eventually these images became part of Frank’s first photography exhibit titled “When We Were Criminals” in 2018 at the M+B art gallery in Los Angeles, where each room was organized by theme. Later that year, the Benrubi Gallery in Manhattan featured another one-person show of his work. Both galleries displayed mostly shots from the late 1970s and early 1980s. “A lot of them were people I had given seeds to,” he says. (Editor’s note: Cannabis Business Times has reprinted some of these photographs, with permission from Frank, within this cover story and in a special photo montage.)

Connecting Past and Present

The cannabis industry has morphed into something mostly unrecognizable from when Frank started his cannabis journey in the late 1960s. He believes the attention on the medical and therapeutic uses of cannabis has opened the plant to a new, uninitiated audience that hadn’t yet experienced the plant.

“Older people and these people who never smoked marijuana, they’re finally looking at all the possible benefits of these different cannabinoids. Trouble sleeping, and aching muscles and joints are old-age consequences,” Frank says. He has had numerous friends and neighbors reach out for product recommendations, which Frank will happily oblige or simply fulfill with some especially potent homemade cookies.

This generosity is a continuation of who Frank has always been, whether he’s gone by Mel or Jim. “He’s just one of the best people I’ve ever met,” Holmes says. “There are very few people that I meet where I’m like, ‘Oh, this is like a really good person to like their core,’ and that’s what I always thought about Mel regardless of all the great things he did, and he did a lot for cannabis and cannabis knowledge.”

Holmes adds that it was Frank who brought him into the limelight, allowing him to make connections with other “OGs” who helped make Holmes’ career what it has been so far. “Mel really helped me with that step in the professional direction out of the black market. He’s a very unselfish guy.”

While Frank’s efforts to advance the cannabis industry are immeasurable, some areas still need improvement to make business sustainable for commercial operators. For example, limited access to banking “relegates cannabis operations as second-class businesses,” Frank says. “Cash makes you vulnerable, and not being able to deduct expenses ... shows just how entrenched the ‘Big Lie’ about cannabis still is.”

Federal legalization will do much to relieve some of these pressures, but Frank is under no illusions that such an event would completely change the industry’s competitive landscape.

“And in the summer of 1967, they’re all writing about kids going blind because they took acid and looked at the sun, and how this guy smoked marijuana and jumped off a building. It was all about these horrible things happening. All these college kids and young kids who were doing marijuana and acid, and I’m thinking, ‘I can’t wait to get outta here and try some of this stuff !’” Mel Frank, Cannabis Consultant, author and photographer

“I think California will still dominate the sun-grown market,” Frank says, with interstate commerce forcing indoor producers to search for areas with low production costs. But much like each region’s claim to great microbreweries, Frank predicts that “you’re going to have locals that find good strains of cannabis that have certain flavors and properties” The broader cannabis market will come to reflect diverse tastes and aspirations.

Frank’s garden is one such example of craft culture persisting against commercial headwinds. Despite mysteriously losing his sense of smell starting in 2016, Frank continues to grow his favorite strains in his backyard—although now he’s less worried about raids and much more careful about his seed collection.

He is growing a new Congolese landrace he received from Africa, as well as a Purest Indica and a Northern Lights #5 from AG Seed Company. The latter two were ruined by a storm last year, so Frank is attempting to realize their fullest expression this year.

Like any true scientist, an unending curiosity continues to fuel Frank. This thirst for knowledge is what led him this year to stray from his practice of growing from seeds or from clones he himself produced. He took in a clone from an outside source, a premier variety from Clade9, for an experiment he conducted with Holmes on the differences between growing indoors versus growing outdoors with a local terroir.

“I was probably a little bit crazy,” Frank says, reflecting on all the risks he took during his cannabis career, any one of which could have failed and landed him in prison. But he wouldn’t change anything that has happened to him lest he undo all the positives that have come from his efforts.

“I never expected this, but so many people I meet say, ‘Your book is what got me into this. You inspired me. This is my career now.’ It’s incredible how many people say that to me.

“What can you say: you live a life and you affect a lot of people’s lives in a positive way … What more can you ask for, really?”