Almost 10 years ago, Washington state broke major ground as one of the first two states to legalize adult-use cannabis. After a decade of both success and growing pains, the story of Washington state and cannabis can be read as a classic tale of “pioneer’s dilemma.”

When you’re a pioneer, there is no rulebook, no signposts, no beacon in a storm. Pioneers become pioneers because they understand that even the smartest minds and most careful planning can do little to help remove the uncertainty of moving first. But still they go. That means unintended consequences and unforeseen challenges. In contrast, later-moving states have the luxury of reviewing past successes and failures of others (like those of Washington state) and attempting to validate assumptions and calibrate approaches. They proceed only when they’re sure, emphasizing getting it right rather than getting there first.

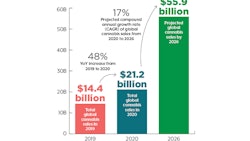

This is not to say that Washington state got everything wrong by being a pioneer or sacrificed itself for the success of others. By many accounts, Washington is second only to California in terms of cannabis market size and total revenue and is a leading light on the global cannabis stage. According to Statista, the total cannabis market in Washington state is projected to be valued at $2.7 billion by 2022, trailing only California’s $7.7 billion.

Washington’s approach to retail licensing has yielded unrivaled access to cannabis products for Washingtonians, with product availability and price competition driving continued growth even in what is now one of the country’s most mature markets. A report from Washington State University, “2020 Contributions of the Washington Cannabis Sector,” pegged the cannabis industry’s total contributions to the state’s gross product at $1.85 billion, and the university projects that number to reach $2.13 billion in 2021.

But many of the state’s cannabis cultivators believe there is ample room for improvement. The state is still recovering from a rocky transition to adult-use from medical-only. Washingtonian cannabis consumers face among the highest excise-tax rates in the country: a whopping 37%. And the rules for competition leave some industry players unable to grow beyond their footprint. There are three primary cannabis business license categories in Washington: production/cultivation, processing, and retailing. Companies can grow and process cannabis, but producers can’t also sell cannabis, and retailers can’t grow and process their own cannabis. If that wasn’t challenging enough, Washington cannabis businesses cannot accept investment from non-Washington state entities.

With Washington’s 10-year legalization anniversary approaching, Cannabis Business Times spoke with key members in the state’s cannabis industry to learn more about the current challenges and opportunities, how cultivators and retailers navigated and shaped these changes during the past decade, and the steps policymakers can take now to make Washington state a true global cannabis competitor.

The State of the Market

The cannabis market in Washington state is growing—but at the benefit of the end-user and at the expense of company profit margins. According to research from Brightfield Group, there continues to be a supply glut in Washington, as in other legal cannabis markets across the country, which is driving down the price of flower both at the retail and wholesale levels. The Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board’s (WSLCB) removal of cannabis business license caps is only expected to maintain the downward pressure on prices, as both the overall cannabis supply increases and price competition emerges among an increasing number of operational dispensaries, Brightfield says.

“Profit margins are slimming for Washington growers, yet due to the influx of capital that continues to pour into the industry, more cultivators are approved, and the market is not showing any sign of correcting itself in the near term,” says Jamie Schau, head of research for Brightfield Group.

When Washington rolled its existing medical cannabis into its broader adult-use market in 2016, the number of permitted cannabis retailers rose to 556, according to the Cannabis Patient Protection Act. According to a WSLCB spokesman, the state has issued 1,054 producer/processor licenses, 221 processor-only licenses and 151 producer-only licenses. Of the 556 allotted for retailers, there are 486 active stores, the spokesman said. That imbalance means growers have to rely on distributors and retailers to engage their customer base.

Initially, the WSLCB set a cap of 334 adult-use cannabis stores statewide, distributed based on local population. This changed, however, with the merger of medical and adult-use markets, though single licensees are limited to three stores.

Lifting restrictions on the license cap will continue to drive growth in the adult-use market, Schau says. According to Brightfield projections, the adult-use market alone will reach $1.8 billion by 2025, compared with $1.4 billion in 2020.

“The approach to licensing has led to excellent access to product for Washingtonians,” Schau says. “On the flip side of the coin, liberal licensing can lead to saturation along the supply chain. While this tends to improve the caliber of retail practices and product quality, as well as lowering price points, industry players can suffer fallout.” With so many retailers competing on price, growers risk taking losses on product surpluses, Schau explains.

Tackling the Vertical Integration Problem

Washington state prohibits vertical integration in the cannabis industry. A company may only simultaneously hold both a producer and processor license. These are known as “tied-house” rules, and they’re vestiges from the early days of alcohol regulation, when the government wanted to clamp down on brewers’ and distillers’ market power while limiting consumers’ alcohol consumption. In the same way that regulators prevented bar owners from distilling their own spirits or brewing their own beer, Washington state has prevented cannabis retailers from growing their own cannabis and growers from selling cannabis directly to consumers.

One goal with these regulations is to prevent market abuse and monopolistic behavior. As written, the WSLCB’s WAC 314-55-018 broadly prohibits any agreements that would cause one industry member to have “undue influence” over another industry member; any advances, discounts, gifts, or loans from a producer/processor to a retailer; or any contract for the sale of marijuana tied to or contingent upon the sale of something else, including other cannabis.

Seen through the lens of 2021, these regulations might seem overly cautious and unnecessarily onerous. But according to some stakeholders involved in the original drafting of the legislation, this was partly by design.

“We put in an incredibly robust regulatory framework and an incredibly aggressive taxation structure to get it to pass,” says Alex Cooley, co-founder of the cannabis cultivation company Solstice. Solstice was among the industry stakeholders who helped craft and provided input on the landmark legislation. The robust regulations were created to make the public, who may be fearful of cannabis, more comfortable, Cooley explains. Today, while much of the industry is still chafing under the strictures of these regulations, the customer has largely won, he says.

“The lack of vertical integration means that any one store isn’t going to grow something like 80% of the cannabis that sits on its shelf,” Cooley says. “That’s a good thing. There are more brands sitting on that shelf. More variety. More competition. The customer wins as a result of that.”

A long-held tenet of business management strategy, vertical integration involves the merging together of two businesses that are at different stages of production—for example, a food manufacturer and a chain of supermarkets. Vertical integration can be a necessary source of revenue growth for companies in the supply chain, but the strategy can also be fraught with risk: What if that food manufacturer lacks the requisite internal capabilities to be a successful retailer of food?

Vertical integration, in theory, could benefit cannabis businesses in Washington state. If a retailer can acquire a cultivation license, that would mean the potential for an additional revenue stream. But, according to Cooley, companies should not diversify just for the sake of diversifying. “Is it a situation where a producer is actually really good at retail? Or is it a situation where a retailer is actually really good at cultivation? What I see more often than not in other states is customers having limited choice depending on what store they go to,” Cooley says.

Still, this regulatory approach has come at the expense of cultivators’ margins, Cooley says. “Because there are so many producer/processors to compete with, our price points get really pushed down,” he says.

And some farmers struggle to find a way to get their products in front of customers. As Cannabis Business Times previously reported in 2019, “discussions over how to solve this problem have coalesced into a new possibility: direct sales.”

Much like the first steps Washington took to create a more consumer-friendly wine industry, allowing wineries to sell directly to consumers at tastings and events, WSLCB officials and state legislators are considering allowing direct sales to consumers at cannabis farms. This makes sense, as the WSLCB also is the state regulator of alcohol sales, and so its cannabis rules have closely tracked the liquor and wine industries.

“The easiest and most off-the-shelf solution would be to treat us like beer and wine,” Cooley says.

For growers, direct sales would be a less risky form of vertical integration. Growers would not necessarily be opening their own stores in downtown centers—just selling their product directly to consumers like how wineries and craft brewers do now.

“It’s important that there’s a conversation about vertical integration and direct sales—and that we distinguish between those two things,” says Crystal Oliver, executive director for the Washington Sungrowers Industry Association and co-founder and former owner of Washington’s Finest Cannabis. “When I think about vertical integration, I think about a large corporation trying to consolidate their supply chain to realize cost savings. But for us, this is just about getting our product to the consumer—because right now the farmers can only access the consumer through retailers.”

Though Oliver sees support from legislators for permitting direct sales, passage of legislation remains uncertain.

Attracting Out-of-state Investment

Washington state law requires all cannabis investors to have established residency in Washington for at least six months. During the past several years, measures have been introduced to remove the residency requirement and permit minority ownership status for non-resident investors, but they all failed to advance.

“We’ve got some amazing brands and some amazing farmers. But the fact that we didn’t allow out-of-state ownership has hurt us,” Oliver says.

The lack of out-of-state investment could impact Washington cannabis businesses if there is a national legalization scheme, notes Jeremy Moberg, owner of CannaSol Farms and founder of the Washington Sungrowers Industry Association.

RELATED: Sun-Grown Success: Jeremy Moberg of CannaSol Farms lights up the Washington cannabis market.

“Washington has some of the best brands in the country and definitely is one of the best experiences for consumers with so much variety at a great price,” Moberg says. “Unfortunately, I don’t think many of these great Washington brands are ready for national legalization.”

The reason, Moberg says, is Washington’s cannabis businesses are not well-capitalized, and investors have been wary of the Washington market because of the current regulations. One way for Washington state cannabis businesses to compete with companies in other states if there is a nationwide legalization scheme would be to form co-ops, Moberg says. These co-ops would combine the resources and capabilities of multiple Washington state cannabis growers with growers from other states (Oregon, for instance), with the idea of serving national markets more cost-effectively if legalization happens. But current restrictions on out-of-state ownership make that model difficult to set up in the interim, Moberg says. Washington state businesses cannot even begin those discussions with potential out-of-state partners, whereas companies in other states that permit cross-border ownership have an advantage.

“Washington companies are going to be largely left out of the national market when that happens, [as they are] under-capitalized and not able to navigate the complexities of a national marketplace,” Moberg says. “I hope I am wrong, because there are a lot of undervalued companies in Washington that should become national brands.”

Putting Social Justice Front and Center

Though Washington was one of the first two states (Colorado being the other) to legalize adult-use cannabis, the state has only recently begun to address social equity in the cannabis industry.

In 2019, Washington Gov. Jay Inslee signed legislation (SB 5605) to give people convicted of misdemeanor marijuana possession offenses the chance to apply to the courts to vacate those decisions. In 2020, Inslee signed a bill (HB 2870) to allow state regulators to direct unused cannabis business licenses to people from communities of color.

Now legislators are looking to expand on these measures to get more cannabis business licenses into the hands of entrepreneurs of color. One pending bill (HB 1443) would direct the WSLCB to ensure that licenses are not issued disproportionately to white growers.

According to self-reported data compiled by the WSLCB and shared with Cannabis Business Times, 82% of cannabis retailers are non-minorities, while only 7% are Asian, 4% are multi-racial, 3% are Black, 2% Hispanic/Latino, and 1% other. The board does not collect the same or similar data for other license categories, a spokesman said.

Joy Hollingsworth, chief operating officer of Hollingsworth Cannabis Company and Hollingsworth Hemp, both family- and Black-owned companies, says that while she is pleased the state is finally taking action on social equity, much more can be done to address these problems.

“The communities that were most harmed by the war on drugs were communities of color, and there are people who are still locked up in prison for selling cannabis,” Hollingsworth says. “It doesn’t feel good to know they’re still in prison but yet there’s this entire industry that’s been made off of this drug.”

RELATED: The Company You Keep: Strong family ties, sustainable choices and adaptability have allowed The Hollingsworth Cannabis Company to find its place in Washington’s mercurial cannabis market.

Hollingsworth says lawmakers should take bolder actions to fix the problems. Legislators can start, she says, by directing a portion of the excise tax assessed on cannabis toward fixing schools, roads, and infrastructure; stimulating economic development in communities of color; creating college scholarships; feeding the hungry; and bridging the digital divide. Currently, most of the cannabis tax revenue goes toward Medicaid and the State General Fund.

At the same time, Hollingsworth says, Black cannabis entrepreneurs should be afforded the same opportunities as anyone else.

“Nobody wants a handout,” Hollingsworth says. “We just don’t want to be pushed down as we’re standing up.”

Pioneer’s Preference

Despite its regulatory challenges and controversies, growers who Cannabis Business Times spoke to expressed optimism for Washington state’s future as a cannabis player on the world stage. As evidence, they point to some natural advantages: The state is blessed with a temperate climate, rich soil, and abundant water sources which have helped make Washington a leading producer of apples, hops, potatoes, and wheat. According to the Washington Farm Bureau, the state is the third-largest food and agricultural exporter in the country and represents 12% of Washington state’s overall economy. Washington’s grid is also one of the cleanest in the nation, with much of its electricity coming from hydropower.

Though Washington might never eclipse California in terms of market size, the state can be a true powerhouse.

“We have done this longer than most, but we have so much more opportunity to do it so much better to be truly a global player,” Cooley says. “It just comes down to whether our legislators and regulators give us that room to run. ... I love our farmers and this industry. And I would love for us to be able to offer all of what we do to anyone who could ever want it in a truly free marketplace.”