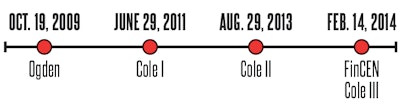

In Cannabis Business Times’ April issue, our column “Make Your World Safe for a Banker” (bit.ly/TechnicallySpeakingApril) reviewed the FinCEN memo that set guidelines and priorities for bankers in dealing with cannabis businesses, and the Yates memo. The Yates memo was written by former Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates (who served briefly as Acting Attorney General this year before being dismissed by President Trump), and it is what bankers really are afraid of in dealing with cannabis businesses. According to the 2015 memo, which Yates wrote to Department of Justice (DOJ) prosecutors, the DOJ will not settle prosecutions against banks or other companies unless the individuals involved also are prosecuted criminally (jail) or civilly (sell the house to pay the fine). In addition to those memos, however, every cannabis license holder should be aware of four other Department of Justice (DOJ) memos: The Ogden memo, and the first, second and third Cole memos.

A Brief Background

In 2009, the Ogden memo steered federal prosecutors away from participants in state-regulated medical marijuana programs. The memo from U.S. Deputy Attorney General David Ogden pointed out that prosecutions of patients or caregivers using or growing marijuana in compliance with state law would be an inefficient use of limited federal resources. OK.

In 2011, U.S. Deputy AG James Cole issued in Cole I a DOJ concern with state-authorized, industrial marijuana cultivation, and said the Ogden memo was not meant to shield such activities from federal enforcement. Not so OK.

What Matters Today

On Aug. 29, 2013, in Cole II, Cole identified eight DOJ enforcement priorities for U.S. attorneys:

- Preventing marijuana distribution to minors;

- Preventing revenue from the sale of marijuana from going to criminal enterprises, gangs and cartels;

- Preventing the diversion of marijuana from states where it is legal under state law in some form to other states;

- Preventing state-authorized marijuana activity from being used as a cover or pretext for the trafficking of other illegal drugs or other illegal activity;

- Preventing violence and the use of firearms in marijuana cultivation and distribution;

- Preventing drugged driving and the exacerbation of other adverse public health consequences associated with marijuana use;

- Preventing marijuana growing on public lands and the attendant public safety and environmental dangers posed by marijuana production on public lands; and

- Preventing marijuana possession or use on federal property.

Cole III and FinCEN cited COLE II’s eight priorities, none of which raise any particular issues for the state-legal cannabis industry. In discussing the Cole memo, most people are referring to Cole II and those eight priorities.

Cole II and III, however, state something more than the DOJ’s enforcement priorities.

“Something More”

That “something more” is the tension between state and federal law, and the efforts of certain individuals and institutions to resolve it.

The federal government is aware that for both constitutional and practical reasons, general criminal law and the vast majority of criminal enforcement have been, and will be, matters of state law. Federal officials also know that the state-licensed marijuana industry, with its regulations and taxes, works against black-market interests. The result is a continuing ambiguity between state and federal law, and a lack of certainty regarding federal enforcement.

These results are particularly troubling to federal officials. If a federal official were to move to legalize marijuana, he might antagonize a significant portion of Congress and accomplish nothing other than to lose his job. Similarly, if a federal prosecutor were to zealously enforce federal law against licensed participants in a state marijuana program, she might annoy the state’s congressional delegation and also lose her job.

Federal officials also do not want to stir up constitutional (federalism, Commerce Clause) issues that would cause another series of problems. One should note, however, that Cole II and Cole III each prescribe strong and effective state regulatory and enforcement systems. In effect, the memos threaten federal action in the event that federal-level interests find that state systems do not control threats to federal enforcement priorities.

As a consequence, we are left in a legally ambiguous world in which we must operate.

More About “Something More”

During the 1930s, the states and the federal government faced issues surrounding “intoxicating liquors,” similar to the issues before us today with marijuana. The resolution was the Twenty-first Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which states, in relevant part:

Section 1. The eighteenth article of amendment to the Constitution of the United States [prohibition] is hereby repealed.

Section 2. The transportation or importation into any State, Territory, or possession of the United States for delivery or use therein of intoxicating liquors, in violation of the laws thereof, is hereby prohibited.

Some states wanted to repeal and other states wanted to continue alcohol prohibition. The Twenty-first Amendment resolved the matter by making traffic in intoxicating liquors illegal only if it were in violation of state law. Otherwise, commerce was legal at both the state and federal levels.

The Twenty-first Amendment left control of the alcohol industry to each state. The resolution of federal-state tension, when some states would prefer to end prohibition, and others would not, was invented some time ago.

Our industry’s problems arise from a statutory prohibition in the Controlled Substances Act rather than from a constitutional prohibition. As such, our fundamental problems could be resolved through the passage of a simple congressional statute allowing each state the power to regulate marijuana within its borders.

Note: The authors do not provide legal, accounting or tax advice. This material has been prepared for informational purposes only, and is not intended to provide, and should not be relied on for legal, accounting or tax advice. You should consult your legal, accounting and tax advisors before acting on any related matters.