In January 2023, the team at Rebel Spirit Cannabis in Eugene, Ore., ran a batch of flower through R&D testing in preparation for new standards coming in March. CEO Diane Downey and her husband, COO Chris Bechler, along with the rest of the Oregon cannabis industry, knew that times were changing. Proactive R&D testing was one way to prepare.

The results on that batch’s first microbiological contamination test were inconclusive: Portland had been hit hard by a snowstorm, which kept lab employees at home for a few days and which left samples like Rebel Spirit’s flower on the culture plate for too long. The flower batch passed a subsequent test, giving team members the green light to ship that flower to dispensary shelves, as they’ve done since first operating in the state’s medical cannabis market, circa 2015. The cultivar, Mafia Funeral, typically sold well in the Oregon adult-use market, Downey says.

In late June 2023, the Oregon Liquor and Cannabis Commission audited a swath of flower products in stores, double-checking SKUs for heavy metals and microbiological content. This audit included the Funeral Mafia batch. It failed—for trace amounts of Aspergillus. Downey was in her office when she learned of the news, not through an OLCC representative, but rather through a friend who had emailed a sympathetic message. Downey quickly searched the internet for what, exactly, this friend was talking about.

“We were just mortified,” Downey says about the product recall notice that OLCC sent on June 26. “Talk about undies bunched up high. We were fit to be tied, just because it felt so unfair. The OLCC never asked, ‘Hey, what went on with this?’”

Even though the Rebel Spirit flower in this case had been harvested and tested prior to March 1, a new era had dawned in Oregon. What went on with Rebel Spirit’s Mafia Funeral in January 2023 is the same thing that’s gone on across the state all year: sudden testing failures, general confusion over Oregon’s new rules, rigorous social media debate over public health standards. For a mature cannabis market already reeling from tumbling prices and soaring costs—and that’s just for starters—this new regulatory hurdle thrown at growers was quickly seen as a potential death knell.

So, what’s really going on here?

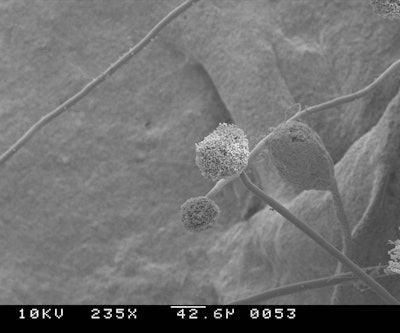

Oregon began mandating a new suite of compliance testing on March 1, including benchmarks for harmful heavy metal content (mercury, arsenic, cadmium and lead) and microbiological contaminants (Aspergillus, E. coli, and salmonella). On face value, this move simply brings Oregon up to speed on compliance testing, in line for the most part with other U.S. cannabis markets; Oregon has been slow to adopt new testing policies. But one microbiological contaminant threshold has caused a stir over the past few months: the testing for four pathogenic species of Aspergillus, a common mold.

Oregon Administrative Rule 333-007-0390, “Standards for Microbiological Contaminants Compliance Testing,” reads in part: “A batch fails microbiological contaminants testing if … the laboratory detects … the presence of any of the following species of pathogenic molds in one gram of sample: Aspergillus flavus, A. fumigatus, A. niger and A. terreus.”

Because Aspergillus strains are ubiquitous in open-air environments, preventing “the presence” (read: a single live spore, for example) of this mold is seen as a fool’s errand, one requiring either fungicide application or post-harvest remediation. This is true to an extent; nevertheless, fail rates for flower and infused prerolls have skyrocketed relative to the era before March 1, 2023.

That said, Rebel Spirit has not had another single failed test for Aspergillus content in this new era, which makes the recall all the more frustrating. Many other companies in Oregon have not been so fortunate, however.

Myron Chadowitz, owner of Cannassentials, also based in Eugene, spoke with Bechler about Rebel Spirit’s weird inconclusive test back in January. The two growers discussed the new rules and tried to wrap their heads around what this might mean for the industry.

“This could be a big issue in Oregon,” Bechler recalls saying.

Chadowitz remembers the conversation differently, with the general tone of the call being: “We’re all fucked.”

The New Era

Life comes at you fast. From Jan. 1 to Feb. 28, 2023, the state of Oregon recorded only 41 R&D tests for microbiological contaminants (Aspergillus/E. coli/salmonella) in cannabis. Four batches of flower failed that test.

But from March 1 to June 30, as growers sought feedback on any Aspergillus content in their cannabis, the fail rate shot up fast. R&D tests for those microbiological contaminants failed at a rate of 23.19%.

Prior to March 1—even prior to 2023 in general—R&D tests were run in Oregon almost solely for phenohunting purposes, to help growers get a better understanding of, e.g., terpene profiles in new genetics they were growing. Now, they are a near necessity, a preventative check on the new pressures of regulations. Already, many Oregon growers were teetering on the brink. (“What is the thing that’s going to send us over the edge?” Chadowitz often finds himself asking his business partner, perhaps rhetorically, perhaps not. “After fighting for so many years and riding out every up and down, every positive, every negative, we’re burnt out.”) The Aspergillus issue and its attendant testing costs have made the business landscape that much more perilous, especially for smaller growers holding fast to razor-thin margins in the first place.

So, the R&D tests are one thing; early fail rates are relatively high. When it comes to compliance tests—the actual OLCC-mandated tests that products must pass before being sold to dispensaries—the fail rate since March 1 hovers around 10% for flower and infused prerolls. By and large, concentrate products, like live rosin or shatter, will not retain any presence of Aspergillus or other mold.

For growers operating in a market that still boasts a 50.5% market share of flower products, this leaves few apparent options on the table:

1) Take your chances with the testing labs, crossing your fingers for a pass. This is not as straightforward as it sounds, with many growers reporting anecdotally a certain “randomness” to the pass/fail rate on these qPCR tests for microbiological contamination—including Rebel Spirit’s own confusing start to the year. Chadowitz has seen similarly unclear results. “When you combine the sensitivity of the test with the fact that Aspergillus is ubiquitous, that means that … if one spore happens to land on your sample, you’re going to get hit,” Chadowitz says. In other words, for growers operating outdoors or in greenhouse environments, especially: Good luck.

2) Remediate your failed batches of cannabis flower (the prescribed next step, according to Oregon law) with any number of radiation service providers.

3) Use a fungicide to eradicate any trace amounts of Aspergillus.

4) Pre-remediate your flower with any number of those same radiation service providers.

5) Shut down your operation. (More on this later.)

Grasping the reality of Aspergillus spores floating through his greenhouse environment, Chadowitz chose the pre-remediation route, reluctantly. “We’ve been researching and researching and researching [different services], because we have to continue our cash flow,” he says.

He eventually landed on a provider that uses a “low-grade ozone solution,” he says. Whether the remediation or premediation is done by ozone or X-ray or ultraviolet light, there is no requirement that growers or retailers acknowledge that treatment on product labels. Chadowitz sees this as a sticking point, one that further obfuscates the challenges facing the industry and keeps the consumer in the dark. He went ahead and affixed his own labels, noting that those certain Cannassentials products had been “Treated by Irradiation.”

“And of course there was pushback from the customers!” he says. “It changed the terpenes, and people don’t necessarily want to smoke it.” Sales have not been great this summer.

According to OLCC data, licensed retailers recorded $473.5 million in cannabis sales during the first six months of 2023, representing a 7.4% dip compared to the same period last year.

That preremediation may solve the short-term problem of merely getting on store shelves, but, for Chadowitz, this emerging testing regime has cast doubt on the entirety of his operation.

“It’s putting me out of business,” he says. “The costs involved in the extra testing, the remediation, plus everything we’re doing around the farm to try to beat this Aspergillus thing—plus having to hold flower back—we are in our death throes right now. But we’re not giving up. We’re dedicated to growing the cleanest cannabis we can.”

Back in January, the business prospects for 2023 were looking good: Cannassentials had just come off a first-place finish for Spritzer in the sungrown flower category at the Oregon Growers Cup, and Chadowitz had been working with retail partners to incrementally raise prices and bounce back from the tricky economics of 2022—all while trimming some input costs. Things were looking up for Cannassentials. “If you’d have talked to me in March, I was on top of the world,” he says.

So, why now?

The Aspergillus Story

There are hundreds of species of Aspergillus. In Oregon, labs are only screening for four of them, including A. fumigatus, which, in October 2022, the World Health Organization added to a new fungal priority pathogens list, indicating “unmet research and development needs and perceived public health importance.” (Grouping those different species into the catch-all name Aspergillus is a bit of a misnomer, but for the purposes of the immediate testing issue it will suffice.)

Tess Eidem, Ph.D., owner of Rogue Micro, recently tried to set the record straight in a newly published video. Eidem is a microbiologist and food safety professional who works in the cannabis space, and she’s been active on many LinkedIn threads debating the Aspergillus issue in Oregon.

In her video, Eidem describes the four species tested by Oregon as pathogenic, while other species are toxigenic or immunogenic. The four in question in Oregon can cause infections in the lungs—known as aspergillosis. As to why there’s no cited threshold in Oregon for Aspergillus content for the sake of public safety, Eidem says: “No opportunistic pathogen [such as these Aspergillus species] has an established infectious dose.”

But she is clear that A. fumigatus, for one, is dangerous. “I don’t mess with this organism,” she says. “It’s serious business.” And Oregon is not alone in this crackdown on Aspergillus content in cannabis.

Colorado began mandating Aspergillus testing on July 1, 2022, distinguishing Aspergillus content from what had previously been a broader “total yeast and molds” category. See, too, the phenomenon in Michigan. Any Aspergillus content will fail.

According to Americans for Safe Access, 22 U.S. states currently mandate that Aspergillus be “absent” or “not detected” in microbiological contaminant testing.

But, according to published literature, the connection between cannabis and aspergillosis is tough to pin down.

“We don’t have any research or data to cite that show people have fallen ill from inhaling Aspergillus through cannabis products,” OHA spokesman Jonathan Modie told Willamette Week in April.

In public records provided by the OHA to Cannabis Business Times, the agency reviewed references to pathogenic Aspergillus and cannabis in studies published from 1975 onward. The 1975 case, co-authored by Anthony Fauci, notes “A. fumigatus causing pneumonitis in a patient who buried his marijuana in the ground for ‘aging.’” An oft-cited 1983 case insists that “the use of [cannabis] assumes the risks of both fungal exposure and infection, as well as the possible induction of a variety of immunologic lung disorders.” A 2011 study flagged in documents provided by OHA does not mention “cannabis” or “marijuana” but rather “cigarette smoke, bacteria, mold, microbial toxins, and chronic lung inflammation.” On a cursory reading, consensus is difficult to identify.

According to the OLCC’s June 26 product recall notice, referencing Rebel Spirit’s flower as well as two other companies’ recalled products, “Consumers who purchased the recalled products are encouraged to destroy them. The OLCC has not received any health-related complaints from the use of the recalled products. OLCC staff has worked directly with retailers to halt the sale of the contaminated products, and will continue to look into the matter. Consumers with health-related concerns about a recalled product should contact the Oregon Poison Center at 800-222-1222, or their medical provider. Consumers who consumed this product may experience respiratory irritation.”

Downey points out that there’s little clarity in that language: In one message, consumers are told that no health-related complaints are on file, and yet those consumers with health-related concerns should call poison control. What’s a “health-related concern,” exactly? What’s a cannabis consumer to do? What’s a dispensary employee supposed to say to inquiring patients?

The evolution of testing standards is one of the pillars of the legal cannabis industry. At no point has the broader U.S. industry reached consensus on what testing standards should be. To that end, Americans for Safe Access in July 2023 published a report titled “Regulating Patient Health: An Analysis of Disparities in State Cannabis Testing Programs.” Across the board, U.S. state regulatory agencies are working from different playbooks when it comes to testing standards. Each state has its own idiosyncrasies, with many borrowing best practices and dubious practices from other states and often working with private companies to sort out a coherent approach to cannabis lab testing.

That’s where we begin in Oregon.

Where Do New Testing Regulations Come From?

In January 2019, the Oregon Secretary of State published an audit of the Oregon Health Authority (OHA) and the Oregon Liquor Control Commission (now known as the Oregon Liquor and Cannabis Commission, the OLCC). The audit was titled, “Oregon’s Framework for Regulating Marijuana Should Be Strengthened to Better Mitigate Diversion Risk and Improve Laboratory Testing.”

The audit pointed out that the OLCC’s own Labs Technical Advisory Committee had recommended in July 2015 that the state mandate testing standards for several Aspergillus varieties.

But the Secretary of State authors were wishy-washy on the matter, noting that expanded microbiological tests could heap an extra 30% in total testing costs onto Oregon growers.

Furthermore, research was lacking in this area. “Risk areas may also vary from state to state, depending on differences in cultivation and processing methods, and preexisting environmental concerns. Risk areas may also vary by region in Oregon, which could be a factor in researching and establishing testing requirements,” the authors concede. “OHA may consider reviewing its current testing panel and reevaluating the risks of consumer exposure to certain pesticides, microbiological contaminants, and heavy metals.”

Nonetheless, when the audit was published in January 2019, the Oregon Secretary of State gave the OHA and the OLCC one year to “perform a thorough study on the potential impacts and presence of microbiological and heavy metal contaminants in marijuana products, to make an informed decision on adding them to testing requirements, potentially in consultation with a reference lab.”

OHA agreed that this was important, with then-Director Patrick Allen writing, “While OHA agrees with this recommendation, there are currently no resources to conduct such a study. Resources would need to be allocated for this study to occur. In the absence of dedicated resources to conduct a thorough study, OHA will reach out to other states with legalized marijuana to request their data related to testing for specific microbiological and heavy metal contaminants. OHA can also convene a rules advisory committee to seek guidance on testing for microbiological and heavy metal contaminants in marijuana products.”

Throughout 2020, the OHA’s Oregon Medical Marijuana Program Rules Advisory Committee held three meetings to discuss these testing rule changes and other issues. Representatives from cultivation businesses and testing labs were present. In the meeting minutes, Aspergillus is not mentioned; rather, the bulk of the discussion revolved around heavy metals and mycotoxins, as well as potency testing and more general regulatory definitions. The committee recommended that further discussion take place, and the OHA set up a workgroup that met in the winter of 2020 and early 2021. "Recommendations from this workgroup influenced a set of draft rules that were presented to a second Rules Advisory Committee that met in the fall of 2021," according to an OHA spokesperson.

Notably, Medicinal Genomics, a research and development product manufacturer that works with cannabis genetics and microbial detection, chimed in as those drafts were being developed. On Dec. 10, 2021, Sherman Hom, director of regulatory affairs at Medicinal Genomics, sent a list of recommendations to Margaret Flerchinger, operations and policy analyst at the OHA. Hom’s recommendations, obtained via public records request by Cannabis Business Times, were meant “for modification of the proposed draft regulations that delineates the required microbial testing regime.” (sic)

Read the full letter here. Here are several points covered in the letter:

- The OHA’s proposed draft rules, ca. Oct. 20, 2021, originally outlined the tests for the four Aspergillus species, as well as “total yeast and mold,” a familiar category throughout the U.S.. Medicinal Genomics pushed back on that, writing: “Our first concern is that total microbial count tests (‘indicator tests’) like Total Yeast and Mold do not test directly for the presence of any specific human pathogens.” (Emphasis MG’s.)

- Medicinal Genomics suggested that E. coli and salmonella be included in this new testing rule.

- “Since these microorganisms are dangerous to human health, the action levels for all six tests should be ‘None detected/gram,’” Hom wrote.

- Then the Medicinal Genomics team gets into the how of this required microbial testing regime, outlining new methods for this process, as opposed to the plating methods used at labs: “Medicinal Genomics also recommends that the required microbial testing for medical and adult-use cannabis and cannabis products rules should include a statement concerning allowable methods to read:

- “A validated method using guidelines for food and environmental testing put forth by the USP, FDA and AOAC Appendix J and cannabis as a sample type; or

- “Another approved AOAC, FDA or USP validated method using cannabis as a sample type. NOTE: ‘Another approved AOAC, FDA or USP validated method using cannabis as a sample type’ may include molecular methods, such as qPCR.”

Medicinal Genomics is the developer of PathoSEEK qPCR detection assays. In fact, the company’s AOAC-certified qPCR performance test method uses cannabis as the sample type and detects the four Aspergillus species cited in Oregon—and it was approved by the AOAC on Aug. 10, 2021, just four months before Hom’s letter to the OHA.

According to the published rule that emerged after this back-and-forth, Oregon Administrative Rule 333-007-0390, “Standards for Microbiological Contaminants Compliance Testing”: “Aspergillus speciation testing as required … of this rule shall be performed using a qPCR analysis or other DNA-based method that has been certified by an independent scientific body.”

Not for nothing, a basic Google search for “aspergillus testing cannabis” delivers a Medicinal Genomics article as the No. 1 result—an article titled, “Aspergillus: The Most Dangerous Cannabis Pathogen.”

Further Amendments to the Rule

Two months after Hom’s letter, the OHA convened a hearing on this administrative rule change, held on Microsoft Teams. A March 16, 2022, report outlines the public comments received at this hearing. Hom had filed written comments ahead of the hearing, advocating for tighter language on the Aspergillus speciation testing method, which was later added to the rule. Representatives from cannabis remediation companies like Willow Industries and VIST Labs also took the opportunity to lend their thoughts in written form.

As Chadowitz and others in the Oregon market have said, one tool to earn compliance with hardline Aspergillus standards is to remediate cannabis flower after a failed test (or even after harvest—or before harvest, for that matter). Chadowitz and other growers interviewed by CBT reported that remediation companies have solicited their business at a non-stop clip all year, repeatedly calling and offering their services.

Ultimately, Oregon Administrative Rule 333-007-0390 does address the matter. “If a sample from a batch of marijuana or usable marijuana fails microbiological contaminant testing the batch may either: (A) Be remediated using a sterilization process; or (B) Be used to make a cannabinoid concentrate or extract if the processing method effectively sterilizes the batch, such as a method using a hydrocarbon based solvent or a CO2 closed loop system.” The “sterilization process” remains broadly open to interpretation, but several such processes are available on the market, most of them involving ozone or X-ray or ultraviolet light.

Nonetheless, that open-ended language materialized in the new rule only after input from remediation companies themselves.

Earlier drafts of the new rule only allowed cannabis producers to pursue what is now option (B), using a batch of failed cannabis flower to “make a cannabinoid concentrate or extract” or destroy the product.

Jill Ellsworth, founder and CEO of Willow Industries, wrote that the rule needed something more:

“We suggest modifying 333-007-0450: Failed Test Samples, as follows:

“(6) Failed microbiological contaminant testing. (a) If a sample from a batch of marijuana or usable marijuana fails microbiological contaminant testing, the batch may be sterilized using a method that does not change its form, such as ozone. It may also be used to make a cannabinoid concentrate or extract if the processing method effectively sterilizes the batch, such as a method using a hydrocarbon based solvent or a CO2 closed loop system.” (Emphasis Ellsworth’s.)

Willow Industries’ decontamination systems use ozone. (“Ozone effectively attacks the bacteria and mold that it encounters because the newly bonded, unstable third atom releases and breaks down cell walls. The cells eventually die as this process repeats itself,” according to the company’s website.)

“Changing [the rule] as suggested above would ensure that operators can use processes like ozone to sterilize usable marijuana that fails these new microbiological tests,” Ellsworth wrote. “This will lead to better economic outcomes for Oregon patients and businesses, while protecting public health and smoothing the rollout of these new regulations.”

She was not alone in advocating such language.

Christian Hageseth, COO of VIST Labs, wrote: “If cannabis flower fails state testing, the current protocol is to send it to extraction or to be destroyed. This leads to a 70% loss in product value when the flower goes to extraction, leading to economic losses for cultivators. We propose the language change that will allow for a process to pasteurize cannabis without changing its form in order to meet state testing level thresholds of 10,000 CFU/g. This language change would accommodate for a pasteurization process, instead of immediately moving to extraction below the 100,000 CFU/g level.” (The CFU metric Hageseth uses is in reference to a proposed total yeast and mold threshold that ultimately was not put in place by the OHA.)

VIST’s own CryoPasteurization process “kills microbial contaminants to safe pasteurization levels … while maintaining the integrity of cannabis and protecting terpenes and cannabinoids,” according to the company’s website.

The March 16, 2022, hearing included input from other stakeholders, too: growers and testing lab owners, mostly. Based on OHA feedback noted in the report from that hearing, none of their feedback was specifically incorporated into the rule itself.

Then, on March 31, 2022, the new testing rule was formally announced, along with a litany of other regulatory changes, in a neat, circumspect document that finally brought cannabis growers into the conversation.

What’s to Come

On July 4, 2023, Trent Hancock spent his holiday cutting down his cannabis plants and shuttering his operation, Creswell Oreganics, based just south of Eugene.

“We decided to shut our grow down, because a lot of the people we know, who are really good growers, are failing right now,” he says. “They’re all saying the same thing. At first I wasn’t taking this Aspergillus stuff all that seriously, but the people I know who have extremely high-quality flower are saying, ‘Hey, we’re going to have to start spraying [fungicides or pesticides] now to prevent this, because we’re failing.”

Hancock opted out of that proposition.

Instead, he has decamped to Montana, where he will manage a vertically integrated small business. He has past ties to Montana’s cannabis market, so it’s a natural fit, but nonetheless he feels his hand has been forced.

Based on anecdotal chatter on LinkedIn and elsewhere, Hancock is not alone in moving out of the Oregon market.

Chadowitz says the question of Cannassentials’ future comes up daily with his business partner.

“The really scary part is we’re talking about it constantly now,” he says. “It’s a constant conversation: What are we doing? What is the thing that’s going to send us over the edge? What is the thing that’s going to shut us down? Honestly, if this shuts us down, at least we know we tried our hardest. That’s where we’re at. We’re at this acceptance level, and it’s really scary.”

As far as this most immediate testing issue goes, there are several major fronts in the narrative. On one hand, there’s a legitimate public health threat in Aspergillus content, though it has not been well articulated by regulators or other stakeholders. The OLCC recall notice is one example; the convoluted list of prior aspergillosis studies is another. Whatever risk pertains to Aspergillus content in cannabis for consumers, it remains to be communicated.

On the other hand, remediation services at play in this story represent a significant business opportunity. There is a market here—in Oregon and elsewhere—for services that irradiate or otherwise amend cannabis flower that has failed microbiological contamination testing.

Caught in the middle are the growers themselves—individuals like Hancock and Chadowitz who are reckoning with deeper questions about their livelihoods and their passions for the plant.

The questions Chadowitz is contemplating are not easy.

For Downey and Bechler, Rebel Spirit is in good shape right now; the company has not failed a test for Aspergillus since that January snowstorm. Bechler suggests that his team’s preventative measures against other mold spores and pests may contribute to solving the Aspergillus situation in his grow environment; it’s hard to say, he acknowledges.

Wherever you look, though, it’s not a rosy summer for anyone in cannabis.

“Looking forward,” Downey says, “my hopes are that Oregon could be a leader when it comes to grappling with this issue and provide some common-sense solutions so that everybody can be safe and companies can be profitable and we can continue to have flavorful, all-natural products. All of those things are achievable. Right now, they’re getting ready to ruin it.”

Editor's note: This feature has been updated to reflect the meetings of an OHA workgroup in late 2020 and early 2021, which covered the development of new microbial testing rules.