Where to grow is perhaps a cannabis cultivator’s biggest decision. Each production style—indoor, greenhouse and outdoor—should be approached differently, particularly when it comes to environmental controls and lighting, according to Travis Higginbotham, cultivation support for Fluence Bioengineering.

With outdoor cultivation, plants are subject to the natural environment and weather patterns, and can only be harvested at certain times of the year. A greenhouse allows for more control over the environment, especially with the addition of supplemental lighting, which lets growers control the photoperiod throughout the year. Indoor cultivation affords full control over the growing environment and year-round production, which can improve consistency in product quality and supply.

“It all depends on what their goals are,” Higginbotham says. “[My] advice … is no matter what, they need to do their due diligence in learning what has already been done in horticulture to some extent. That’s where cannabis is highly lacking in understanding. There are plenty of strategies that have been done in horticulture and floriculture that no one has even thought about in cannabis.”

Regulations will also play a role in a cultivator’s production-style decision, Higginbotham adds, and can include rules on energy usage, plant number and total canopy space.

“[With] other crops and segments of horticulture, you have different species grown all over the United States based on the conditions that fit that crop most readily or wherever that crop is mainly native to,” he says. “So, in cannabis, we want to maintain the same growing schedule throughout the entire country, and so it all depends on what the regulations are. That really has more influence on growers sometimes than regional decisions because in other industries, they don’t have near as many regulations, so they can make a lot of these decisions a lot differently.”

Here, Higginbotham discusses the risks and rewards for each environment, including lighting strategies for each.

Outdoor

In an outdoor operation, many of the environmental factors needed to grow cannabis are available for free. There is usually plenty of airflow and light that has a high intensity and that is applied appropriately to the plants based on the time of day, Higginbotham says.

“There are certain ways that current lighting technologies indoors can’t match this yet,” he says. “So, outdoors, you have the sunrise and sunset, and we understand that during these stages of the day, you have different light qualities—different light spectra—being applied. … Production outdoors can take advantage of that because it’s just natural lighting.”

Cultivators can often grow throughout the day in the summer and achieve larger plants, and as the days get shorter, the plants slowly begin to flower, Higginbotham adds.

However, cultivators are at the mercy of the season when growing outdoors. Pests can be more prevalent, Higginbotham says, and rainfall, dew and temperature changes can cause disease.

“If you’re limited in real estate and you have high plant density, you can cause a lot more disease outdoors, depending on the temperature and humidity changes, mainly based on where you are,” he says.

And because outdoor cultivation depends on natural lighting and the plant’s natural grow cycle, outdoor cultivators usually only get one or two harvests per year, Higginbotham adds. However, if growers want to have multiple cycles within one day, they could build hoop houses around their plants to manipulate the day length with black cloth that can be pulled over the plants, he says.

“And then if they [wanted] some sort of photoperiodic lighting outdoors during short days so they could extend the days with artificial lighting, there are different ways to approach that, but I don’t see many growers doing that,” Higginbotham adds. “They usually just utilize the free sunlight and make their plants subject to the natural day lengths.”

Greenhouse

The decision to grow cannabis in a greenhouse should largely depend on where the facility is located regionally and what lighting is required during each season, Higginbotham says. Cultivators will need to decide how to supplement lighting based on the natural seasons, and will usually require supplemental and photoperiodic lighting, he says.

“Supplemental lighting allows them to use artificial lighting during low light level times of the year,” Higginbotham says. “Mainly, that’s focused on the fall, winter and spring months, when they use supplemental lighting.”

Photoperiodic lighting can also be used seasonally in a greenhouse to trigger different plant development factors based on the plant’s perception of day length, he adds.

“Usually, it’s understood through the term DLI—daily light integral,” Higginbotham says. “So, growers use different strategies like cyclic lighting, daylight extension [and] night interruption strategies with lighting, just to manipulate plant development.”

And while greenhouses offer mild control over the environment, he adds, it can be difficult to fully control the temperature in a greenhouse, especially in warmer climates where the heat can negatively impact certain plant responses, like flowering.

“Some of the struggles are not only just temperature-related based on seasonality, but also you’re subject to winter months and cold temperatures, and you’re having to generate high volumes of heat, and heat dispersion in a greenhouse can be very difficult,” Higginbotham says. “Sometimes, some of the practices that are used for this—like heat burners—usually produce secondary compounds such as ethylene that can cause more issues on the crop than the benefits you’re getting from the heat source.”

Indoor

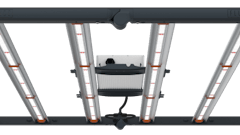

When growing cannabis in a completely indoor environment, growers should first consider their strategy and facility design—whether to implement a single layer of canopy or multiple levels, Higginbotham says.

Cultivators should base facility design decisions on total canopy space, required watts per square foot and energy usage, among other factors, Higginbotham says. In addition, each growing stage—propagation, vegetative and flowering—should be in its own room with its own environment.

“Usually indoors, they have different rooms for each growing stage, so each stage needs to be looked at not only in terms of photoperiod applications, but light intensity needs to be considered because the resulting photosynthetic reactions in the plant accumulate based on how much energy from the light the plant has absorbed. If the plant does not derive enough energy in both length of exposure and intensity (DLI), the plant will not reach its full potential in terms of biomass,” Higginbotham says.

Each stage should have its own lighting strategy in an indoor grow, he says. In propagation, cultivators should start exposing the plant to higher and higher light intensities so that by the time it reaches the flowering stage, the plant is photosynthesizing as quickly as it needs to in order to flower. Assuming propagation is done through cloning, the photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD), or the amount of light that reaching the plants, should start at around 80 in propagation but increase to 250 to 275 by the end of this growth stage, Higginbotham says.

In the vegetative stage, the plant should still experience long day cycles, but growers should also accelerate the amount of light the plant receives on a daily basis—even higher than in propagation. PPFD should reach 450 to 600 during a long day in this stage, Higginbotham says.

“Then, when you switch your photoperiod and you put it into flowering for short day, you automatically have the plant acclimated to high light intensities, so during that short-day cycle, even though your day is much shorter, the plant is still photosynthesizing at the max pace it can under that day length,” he says.

High light levels should ideally be implemented during the flowering stage and the PPFD levels should be from 500 to 1,000, Higginbotham adds, depending on other environmental factors.

There is more emphasis on energy usage in indoor cultivation facilities, he adds, because it is a fully controlled environment where growers must provide plants all their light.

“It’s a lot more energy consumption than in a greenhouse where you’re just supplementing,” Higginbotham says.

There are certain benefits to being in complete control of the growing environment that might outweigh the increased energy consumption and operating costs, however.

“It’s allowing us to have much, much, much more precision to our objectives with the plants,” Higginbotham says. “At the same time, that’s giving us challenges because we don’t yet know where those thresholds are in regard to CO2, airflow, temperature, light intensity, soil moisture, irrigation frequency, nitrogen availability—all of these things we now have precise measurements on, but yet we don’t know the proper ratios of those per crop stage to maximize growth fully yet in cannabis. That’s kind of the exciting part about cannabis and indoor growing in general."