It goes in one end, and only about 10% gets pulled out the other end.

In a nutshell, that’s the first step of the cannabinoid extraction process at vertically integrated Vantage Hemp Co., a large-scale facility in Greeley, Colo., which produces a full range of cannabidiol (CBD) products for customers across the United States and globally. The physical changes associated with hemp processing are similar elsewhere.

But as extractors ramp up operations to serve the growing hemp market, an air of uncertainty hangs around their future.

In August, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) proposed its interim final rule on hemp, which states that any material containing more than 0.3% delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) on a dry-weight basis is still classified as a Schedule I substance. This has led some in the industry to interpret that the DEA may try to regulate in-process hemp extract, as delta-9 THC levels are concentrated during various stages of extraction. It has resulted in a lawsuit from Hemp Industries Association (HIA) and RE Botanicals, a South Carolina-based CBD manufacturer, which is still ongoing.

To understand the full implications of the DEA’s proposed rule, it’s important to understand the extraction process.

Extraction Basics

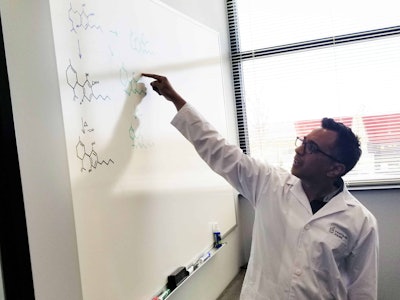

When a hemp plant enters an extraction facility, it contains the cell wall, proteins, fats, waxes, DNA – and, of course, all the cannabinoid compounds cannabis is known for. A few different methods can be used to extract those cannabinoids from the plant biomass. Some popular methods include extraction by solvent, olive oil, steam distillation, liquid hydrocarbon and supercritical CO2.

The CO2 extraction is a scientifically advanced method that involves converting carbon dioxide to a liquid state under increased pressure and decreased temperature, before slowly increasing both pressure and temperature until the liquid reaches a “supercritical” point, when the CO2 is between a liquid and gaseous state.

At Vantage Hemp, the supercritical CO2 is pumped into a chamber with hemp biomass and used to extract out the cannabinoids in that first stage of the refinement process. Anything that is waxy and oily also gets pulled out of the plant to create what’s known as crude oil, a concentrate with a peanut butter-like consistency that typically contains about 50%-60% CBD. The other 90% of plant biomass gets repurposed, recycled or disposed.

RELATED: How HempFlax Uses the Whole Hemp Plant

From that point up until the final state of refinement, the THC levels of the intermediary hemp materials are also concentrated, meaning they are above the legal THC limit of 0.3% (on a dry-weight basis), as defined in the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 (the 2018 Farm Bill).

“What you’ll see during extraction is a tenfold increase in the [cannabinoid] content,” says Deepank Utkhede, the chief operating officer at Vantage Hemp.

“So, if you’ve got 6% [CBD] in your plant, when you extract it, the crude you get out of it will be in the 50-to-60% [range] – so, almost a tenfold increase in that concentration,” he says. “You see the same in THC, because they both have very similar extraction properties. So, it goes from 0.3% to suddenly you’re at 1%-2%, and now you’re non-compliant.”

While THC levels are concentrated in crude, that’s only an intermediary hemp material and is not the final product Vantage Hemp or other extractors are aiming to distribute to consumers.

The next stages of refinement at Vantage Hemp are all purification steps that produce increased concentrations of CBD. Winterization is a multi-step process whereby fats, lipids and waxes are removed by dissolving them with an alcohol followed by cooling to cause them to precipitate out of the solution. The alcohol is then removed through an evaporation process to create what’s known as full-spectrum oil (FSO), which contains about 60%-70% CBD. The FSO then goes through a short-path distillation system that removes additional impurities while still leaving minor traces of beneficial terpenes (aromatic compounds found in many plants) to create a distillate with a potency of about 75%-80% CBD.

Full-spectrum oil and distillate do hold medicinal value, but they too are intermediary hemp material with increased amounts of THC, roughly 2% and 3%, respectively, during Vantage Hemp’s extraction process, Utkhede says. The percentages during those stages of extraction can vary slightly depending on the amount of THC in the original biomass.

“If you want to have a saleable product that’s either the full-spectrum oil or the distillate, you have to go through what’s known as a remediation step,” Utkhede says. “It’s a THC remediation step, where you actively remove THC from those [materials] through chromatography or some sort of chemical reaction but still have all the other cannabinoids present.”

In the final purification step at Vantage Hemp, the distillate goes through a crystallization process where it’s dissolved in another solvent, which is then cooled to cause selective crystallization of CBD and creates an isolate that is greater than 99.5% CBD. In its purest form, the crystallized CBD isolate is a white powder that’s absent of nearly all smell. When it leaves Vantage Hemp, or other extraction facilities, to become a saleable product, CBD isolate is compliant by the legal THC parameters defined in the 2018 Farm Bill.

“We’d have problems if we were selling our product at each step of the way without remediation,” says Dr. Daniel Chinnapen, Ph.D., the chief scientific officer at Vantage Hemp.

“There’s no way to make [crystalized] CBD without going through and having concentrated THC,” he says. “And, really, that’s a percentage thing. It’s not a total amount. So, you could take this one compound or one product that is legal—let’s say it’s below 0.3% [THC]—and you take that same compound and, along the way, just because it’s concentrated, it all of a sudden becomes illegal. Although it has the same THC amount in there, the relative percent is higher. So, it still doesn’t make any sense. It’s just not practical.”

In other words, the extraction process does not create more THC but rather concentrated amounts in either waste hemp material (WHM), such as the byproduct from a solvent that gets pulled out and disposed of, or intermediary hemp material (IHM), which includes unfinished byproducts like crude, full-spectrum oil and distillate that haven’t had THC remediated.

Inevitable Byproducts

Although WHM and IHM are inevitable byproducts of hemp processing, the DEA’s proposed regulations appear to regulate those byproducts.

HIA’s lawsuit alleges that the DEA is misinterpreting the 2018 Farm Bill in its attempt to regulate those extraction byproducts. The plaintiffs argue that Congress deliberately removed such commercial hemp activity from the DEA’s jurisdiction when lawmakers legalized hemp production, including hemp processing, with the 2018 Farm Bill.

Jason Waggoner, the vice president and general manager of Grand Junction, Colo.-based EcoGen Biosciences, a leading vertically integrated wholesale CBD manufacturer and supplier of hemp-derived ingredients in the U.S., says his extractors operate within the spirit of the 2018 Farm Bill, so he doesn’t stay up at night worrying about the regulatory bounds, since WHM and IHM are necessary byproducts of hemp processing.

“In my heart, I just don’t believe that the DEA is actively pursuing folks that are operating inside the regulations,” he says. “I don’t believe as well that we should expect that the DEA is going to do anything other than restate the law. But that is not directed at good operators and fair operators.”

The reason the DEA maintains its party line is because, in some cases, there are “bad operators” and folks who are operating outside the bounds of the law, Waggoner says.

“For that reason, we should never probably expect that they’re going to say anything other than what the legal guidelines are,” he says. “But I don’t believe that they’re out to get me or anyone else in the hemp industry who is behaving in a manner faithful to their regulations. I think they’ve got too much to do than worry about me.”

In addition to extraction, EcoGen runs an end-to-end hemp operation that includes company-owned genetics on catalog, roughly 400 acres of farm, a greenhouse and manufacturing.

While the physical changes associated with crude, FSO, distillate and isolate are ubiquitous as they relate to processing hemp, EcoGen uses propriety extraction and post-extraction processing equipment that is manufactured in house, Waggoner says.

“We don’t use isolate reactors,” he says. “Instead, we use a different process that crystallizes and cleans the isolate, which gets it to a very pure content with no residual solvent … that is unique in the industry.”

While extraction methods vary from extractor to extractor, Waggoner says he thinks about the waste and intermediary hemp materials in a similar fashion to that of alcohol distilleries. For example, when beer manufacturers distill their hops, they’re left with byproducts that are not extracted, such as the organic plant material, which then have to be treated and disposed of properly.

“I’m not an alcohol distiller myself,” Waggoner says. “However, I do know that … as an example, grain alcohols are created regardless of the spirit that you’re creating. And those are not how, for example, a bourbon or a vodka or a gin are sold right there. [They’re] intermediary steps that ultimately get to a finished product at the end through additional chemical conversion, dilutions, distillations – those types of things that allow for us to get to a legally sellable product that goes into the chain of commerce.”

In hemp extraction, WHM and IHM byproducts never leave EcoGen’s tracking inventory, Waggoner says.

Waste Streams

While the 0.3% THC threshold that differentiates between what is considered industrial hemp and marijuana applies to what’s growing in the field from an agricultural standpoint, that allowable limit should not apply to the in-process extraction, says Joy Beckerman, principal of Hemp Ace International, which provides professional hemp consulting, legal support and expert services.

But when it comes to finished extraction products like CBD isolate, or even CBD oil and CBD distillate that have undergone THC remediation, the legal limit of 0.3% THC should remain as is, Beckerman says. Mathematically, that translates to 3,000 parts per million (ppm) of THC.

“That’s a lot,” she says. “In Canada, it is 10 parts per million is what is allowed … to be a legal hemp product. If you have more than 10 ppm THC in your finished hemp product, you [have] a marijuana product.”

If the legal limit for hemp were increased to 1% THC, the concentration threshold for cannabis to have a psychotropic effect, according to the Congressional Research Service’s (CRS) 2019 fact sheet, then finished products would be allowed to have 10,000 ppm, which would jeopardize the extract industry because consumers seeking the non-psychoactive benefits of CBD could experience the intoxicating potential of THC, Beckerman says.

Regardless, extractors would still go through the same channels of processing hemp and still have the same waste streams, Utkhede says.

“Really no part of our waste stream should go into a landfill,” he says. “We should be able to find a home for everything.”

To support research and development, Vantage Hemp signs agreements that allow people to pick up the company’s waste stream for free, whether it’s used biomass that was separated from cannabinoids during the first stage of extraction, or fats and lipids that were pulled out and separated from cannabinoids during winterization. The used biomass could be repurposed as bedding (hemp stalks) or feed (hemp leaves and seeds) for animals that are not for human consumption, while waste fats and lipids could be turned into products like soap, lotion, or even snowboard and ski wax.

Once there’s a commercial use for materials from Vantage Hemp’s waste stream, then company executives sit down and negotiate a supply agreement where people have to pay for the raw materials that they had been getting for free.

“What that allows us to do is basically support the development of new businesses, new entrepreneurs who want to look at new ways to use hemp and the byproducts of our extraction process,” Utkhede says. “But it also allows for the complete use of the plant.”