For some companies, success is tied to bottom lines, investor confidence, and stock prices. For others, it’s about being creative and finding artistry in the process.

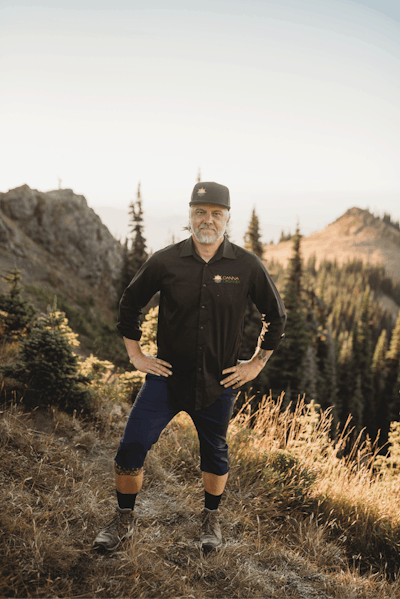

And then there’s the team behind Canna Organix, a Washington-based, Tier 3 cannabis cultivation company located in the northeast corner of Olympic National Park, whose definition of success varies depending on who you’re asking.

“Success means more than our bottom line, and it’s been a way of living and a way of being,” says Wendy Bentley, business manager for Canna Organix. “We want things to operate positively on the day to day. We want people to be happy. … We also value everyone’s home life and we want to give space and support for the inherent things that come up.”

Lead cultivator Kyle Canty’s definition of success takes on more personal tones. “My success is finally maturing,” Canty says. “I lived like a kid my whole life, and then finally I matured into a man—that took me 34 years ... So I feel like that’s my success right now, because it’s helping me be a better father.”

Success for Steve Olson, who oversees the company’s social media, marketing and customer relations, is team members doing their jobs well, leading to the company delivering on its promises to customers and retailers.

Photo by Cassie Johnson

“The property that we were on was quite literally a piece of dirt: It had no power, no water, no fence. It had a driveway into it; that’s what it had.” – Tim Humiston

Kerry Bennett, Canna Organix’s president, finds success in being able to lay in bed at night having pride and a clear conscience that the work he’s doing is helping employees and their families live happy lives.

For Tim Humiston, the company’s founder, success is about how well the team is balancing being a business and being artists with the plant. “Early on we set three goals,” Humiston shares. “Grow product that we want to consume ourselves, sell it at a price that we ourselves would be all right purchasing at, and turn a profit while doing the first two.”

So far, the team has all achieved their own visions of success.

Photo by Cassie Johnson

“Don’t ever tell the plant what it’s going to do. It tells you what it’s going to do.” – Kyle Canty

Finding Paradise

Humiston got his start in the legal cannabis industry at age 18 in the early 2000s as a caregiver in Washington under the state’s I-692 medical program. He and a friend worked as a grower at Seattle’s The Green Cross. At that time, growing was more of a hobby for Humiston, a side gig that taught him about a plant that has fascinated him since his teenage years. His primary job was as a contractor flipping houses. Noticing worrying trends in the housing market starting in 2007 and 2008, he decided to move to the Emerald Triangle with Bentley to learn how to turn his passion into a full-time endeavor. If there was a place in the country they could become cannabis experts, California’s large medical market was it.

“I spent a lot of time pioneering year-round greenhouse production down there,” Humiston says of his time working full-time in Mendocino County, “working on greenhouse controllers and working to start to control the humidity and temperatures and everything in these greenhouses.”

The duo spent the next six years honing their skills, graduating from trimmers to growers as time went on. After Washington voters passed Initiative 502 in 2012, which legalized adult-use cannabis, Bentley recalls turning to Humiston with a question: “Should we try to apply what we’ve learned down here to the new market?”

“Washington has always been home to us—we were from Washington originally,” she says. Humiston liked the idea, noting, “my parents were just starting to get into their 70s at that point… We both decided that it’d be good to get up back around our parents and be able to spend some time up there while the opportunity was there.”

He also saw an opportunity to make a statement about sun-grown cannabis in a state that, in his view, was indoor-grown oriented. “Washington, in its own right, had become a kind of a hub for really good indoor products,” Humiston says. “It just seems so strange to be … trying to mimic what the sun’s doing and mimic the right climate of the outdoors.”

He moved back to Washington six months before Bentley, scouting for locations for a sun-grown cultivation operation. Sequim presented a unique opportunity: Being in Western Washington would grant them the proximity to family they wanted and to larger markets to sell their wares. And while that region of the state typically receives 20 to 25 days of rain in the wettest months and a maximum of approximately 60 percent of possible sunshine during the summer, being in the northeast shadow of the Olympic Mountains means Sequim enjoys about 18 inches of rain per year and more sunshine, according to the Western Regional Climate Center.

Sequim temperatures also are more favorable for greenhouse production than in Eastern Washington, where many of the state’s other sun-grown operations reside. Temperatures rarely crack 90 degrees Fahrenheit in the summers (average highs in July and August are in the 70s) and the lows aren’t extreme, either, averaging 32 degrees Fahrenheit in January, according to data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

While the property wasn’t the picturesque pastoral retreat that he had dreamed about, its location on an industrial-zoned property proved to be auspicious: Not having residential or agricultural neighbors made it easier for the company to receive approval for various needed changes to the property, the founder says.

After meeting with county officials to help quell any community doubt about a cannabis business opening shop, Humiston tapped Olson, a high school friend, to help him and Bentley and a handful of others get started on preparing the property and building the greenhouses. “The property that we were on was quite literally a piece of dirt: It had no power, no water, no fence. It had a driveway into it; that’s what it had,” Humiston recalls.

Photo by Cassie Johnson

“[Budtenders are] our last line of defense before a product goes out to the customer.” – Steve Olson

Customized Success

Today, three greenhouses and seven hoop house structures stand on the 3-acre property. Each greenhouse also houses three smaller hoop houses. “Each one of those internal ones has its own tarp system that allows us to dark out the environment and manipulate the photoperiod so that we can veg and flower plants all year long,” Humiston explains. “Also, the system allows us to a dark ‘em out at night so that we aren’t bothering any of the neighbors with light or anything of that nature.”

The smokable flower grows in greenhouses that Humiston designed and built, and have some unique features. For example, Humiston modified furnaces and ran ductwork under the greenhouses. The heat from those furnaces runs through the ductwork before exiting through vents under the canopy.

“That heat comes out underneath the plants ... rises up through the canopy and wicks the moisture and everything that is in the canopy out and keeps rising. At a certain point, the fans kick in, and we’ll pull that now-moist hot air ... out of the greenhouse while it’s constantly being replaced down below,” Humiston explains.

After failing to find anything that checked all his boxes on the market, the founder also developed his own custom greenhouse controllers using Raspberry Pi single-board computers. The custom controller, details of which are a tightly held trade secret, operates on a predictive system that collects and computes data from both inside and outside the covered structures to provide the optimal environment. “The controller is also working in concert with that heating system to control humidity in a fairly novel way that reduces the cost of reducing humidity substantially,” he shares.

Additionally, the spaces between each structure are packed with outdoor-grown cannabis to max out the company’s licensed canopy allowance. “I just started one year putting them in between the greenhouses,” Canty details. “It worked out: I grew these huge plants that were like 10 or 12 feet [tall]. We ended up getting like an extra 700 pounds that year.” The main greenhouses cover approximately 10,000 square feet, with the rest of the 20,000-foot canopy split between the hoop houses and outdoor crops.

Canty mostly works in the three main greenhouses because those crops require more personalized attention to meet the company’s quality standards. As such, additional technology in the greenhouses is kept to a minimum, as the team favors a hands-on approach for its flower.

“We hand-water everything,” Canty says. “… Each pot gets its own individual attention, and we love it till its end.” Canty oversees a team of eight cultivators who do everything from individual plant checks to feedings by hand. While not the most cost-effective process, this personal approach is part of the team’s goal of “letting the plant express itself naturally,” which the team says yields healthier crops with higher terpene contents.

Photo by Cassie Johnson

“For us, success means more than our bottom line, and it’s been a way of living and a way of being.” – Wendy Bentley

“I let the plant do what it’s going to do,” Canty explains. “Don’t ever tell the plant what it’s going to do. It tells you what it’s going to do… Don’t flip it into flower too soon. Don’t over-water it, don’t overfeed. Just always be nice and light and gentle with it.”

Part of that gentle approach also comes down to how plants are grown. Cuttings start in coco bricks before being transferred to a living soil medium in 20-gallon pots for flowering. The living soil consists of a base of peat, coco and perlite and is amended with compost teas, enzymes, living bacteria, bone meal, blood meal and different guanos. Like with most things at the farm, Canna Organix puts its own spin on the living soil process.

Growers who use “a true living soil, they don’t really [till], and they just keep it all intact every time,” Canty says. “I make sure to break up the pot every time so that I get good aeration. Making sure that my plants can dry out consistently is just key.”

Heavy-feeding plants might also get a boost of liquid nutrients (which typically wouldn’t be used in living soils) near the end of the flowering cycle if a cultivation team member notices low nutrient levels.

Outdoor plants are used for extraction, a process overseen by Troy Russell, another longtime friend who serves as the company’s processing manager. In his role, he oversees everything from harvest to shipping. Russell has been invaluable to Canna Organix, Humiston says, especially in the early days, sacrificing time spent away from family to help build the company. Humiston recalls Russell traveling two hours at the start of the week to be at the farm, him sleeping there during the week, and driving another two hours to see his family on weekends. “Without his help and the sacrifices he made being away from his family, Canna Organix would not be what it is today,” Humiston says.

Breeding for Terpenes

Canna Organix prides itself on its genetic library: Wedding Cake, Zkittlez, Gelato 41 and Do-Si-Dos are staples on the company’s menu. The team likes cultivars with fruity terpenes, and has begun a breeding program—Cannagenex—to develop new flavors. It’s been a two-year process, Humiston says, and new products are just starting to hit the market.

Genetics are “where we’re setting ourselves apart from other grows,” Canty says. The team started the breeding program by recreating some of the industry’s most popular genetics by crossing those cultivars’ parents together, which often is the only option to get those genetics into the state’s legal program due to the federal ban on shipping cannabis across state lines. Now that it has established a reputation for high-terpene varieties (as evidenced by the Dope, Sun and Cannabis Cups the company has won), the team is rolling out new creations.

Photo by Cassie Johnson

“Hit the wrong note a few times. You’re going to end up discovering something beautiful if you allow that environment to thrive.” – Kerry Bennett

Prior to the coronavirus pandemic, Steve Olson, the company’s head of marketing and customer relations, would visit Canna Organix’s dispensary partners and hold vendor days at least twice a year at each location, giving him an opportunity to interact and educate consumers directly about the company’s products. Just as important as customer education is budtender awareness. Budtenders are “our last line of defense before a product goes out to the customer,” Olson says. If Olson can share the company’s story of friendship and collaboration, the budtender can then impart that “energy” on a customer.

Post-COVID-19, however, the company’s marketing efforts have been focused on social media. The company starts teasing new genetics up to six months before they hit the market. “About two to three months before we actually release it, we’ll start teasing it more and more,” Humiston explains. “Quite literally just little bits and pieces trying to catch people’s interest, but not give them enough information so they’re not satisfied with what they got.”

The team also developed what it calls “strain stickers,” individual logos for each cultivar that the team can promote on social media to give strains a recognizable image that customers can associate with the product. “In my mind, [customers who saw the strain sticker] walk into that store and are previewing everything, and they just spot that image they’re familiar with on the shelf on our jar and say, ‘Oh yeah, that’s what I need to try.’”

This is where balancing artistry and running a business coalesce: While the founders would love to conduct R&D all the time, Kerry Bennett, the company’s president, works with them to make sure the operation runs profitably without stifling their creativity. When he feels the team is getting too tense about deadlines or operations, he encourages them to take some time away from the farm so they can reconnect with their creative roots and come up with new ideas and solutions. It’s something he says any company can and should consider doing.

“Take your resources, cut out a budget of your time, your money, your space, the way you think, and on purpose, turn off the function of running and growing a business and on purpose, play jazz,” Bennett says. “Hit the wrong note a few times. You’re going to end up discovering something beautiful if you allow that environment to thrive.”

Creating ‘a Comfortable Place’

Getting in business with friends rarely is a good idea—at least that’s how the old saying goes. For Humiston, however, launching Canna Organix with his friends is what has made the company what it is today: A financially sound operation where everyone is happy and excited to come into work because they know that no matter what’s going on, they are going to be supported by the team.

Cultivating that culture took years of hard work, dedication, and a little bit of ineffable magic.

“I don’t know what we did here, but I think it worked awesome,” Humiston says. “For whatever reason, these people work 8 or 10 hours a day with each other and then go hang out [together] after work.”

Bentley deserves much of the credit for developing that supportive and collaborative culture, Humiston says. When the duo were working in California, he remembers how “she would go to almost no ends to make this a comfortable place for people, providing three highly nutritious meals a day and really focusing on interacting with people on a real human level.” This care continued in Sequim in the form of the numerous cookouts and daily healthy snacks she plans.

Creating that culture starts with hiring the type of people who will find passion in the work. “We’re looking for passionate individuals,” Bentley explains. “We are looking for people that have hobbies … one of my questions is, ‘What do you like to do when you’re not working?’ … because we’ve found that passion towards things translates into being passionate about whatever someone is working on.”

If someone is passionate about their work and how they are doing it, “then they come up with processes or really think things through and give it their all,” Olson shares. By “identifying when people have an idea where they could be doing something better or more efficient and then trying to accommodate that for them,” the whole company gets better from an operational, financial and human perspective.

Who knows—someone’s wrong note could inspire a new melody.