(11/8/2019) Editor's note: This story has been updated for clarity. While David Bernard-Perron's living soil recipe at Whistler Medical Marijuana Corp. (WMMC) was certified organic in 2014, WMMC received its first organic certification in 2013, the year before Bernard-Perron joined the company.

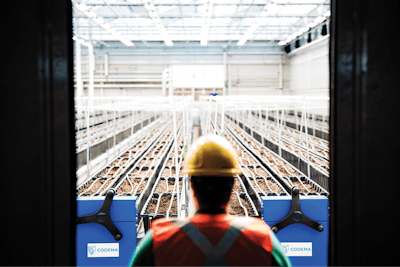

On paper, it’s hard to understand the scale at which The Green Organic Dutchman plans to operate. What does nearly 4 acres (or 1.5 hectares) of cannabis grown under a glass roof look like? What about just under 20 acres, which equates to roughly 8 hectares? How much soil does an organic farm of that size require? What precautions must be taken and what tools implemented to ensure a consistently healthy crop while still maintaining a living soil?

Seeing that scale in person is dizzying: row after row of mobile racks topped with custom-made pots filled with a house-made living soil—a mixture of rich earth, molasses, beneficial microbes, bacteria, fungi, insects, nematodes—masterminded by David Bernard-Perron, the company’s vice president of cultivation operations.

After obtaining his master’s in agriculture from McGill University in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, in 2015, Bernard-Perron moved to the Canadian West Coast and launched his career in the cannabis industry as the head agrologist for Whistler Medical Marijuana Corp., a licensed medical cannabis operation in British Columbia. There, he developed and refined the company’s indoor living soil program.

TGOD, as his current employer is known, hopes to replicate the success Bernard-Perron found in Whistler’s 15,000-square-foot operation, first with the company’s 160,000-square-foot Ancaster, Ontario, facility, then again in its 1.3 million-square-foot behemoth in Valleyfield, Quebec.

Getting to scale has definitely not been easy, and recent headlines about the company losing the funding it needed to complete construction at both sites certainly have complicated matters, but executives remain confident that the setbacks are setting the company up for an even better launch forward.

Second-Mover Advantage

The company headquarters—half a floor at a nondescript office building above a bank near the Toronto International Airport in Mississauga—belies the company’s vision: to be the world’s largest organic cannabis producer. The space doesn’t quite fit the team’s administrative and executive divisions, but no one complains; they know making that organic vision a reality requires time and sacrifice.

“It’s a culture of entrepreneurs that are here from various backgrounds, various industries to create something great that’s long-lasting,” says Drew Campbell, TGOD’s head of marketing. (The company’s headquarters isn’t a Silicon Valley garage, either, which also helps ease cramped tensions.)

Instead of office space, the bulk of the company’s funds have gone into completing construction of its hybrid glass-roof facilities, which, once completed, will officially make TGOD the world’s largest organic cannabis producer with a footprint of more than 1.4 million square feet in Canada alone.

That scale is the major differentiator between TGOD and any other producer in the world, says Brian Athaide, the company’s CEO. “There are ... other organic producers, but they tend to be more craft. We’re the only ones doing organic at scale that nobody’s ever done before.”

Building a facility with the automation and environmental control needed to produce a profitable crop at scale while maintaining organic standards was no easy task. TGOD went through several redesigns that delayed its market launch and increased costs. But Athaide says while those delays prevented the company from enjoying first-mover advantage, they allowed it to learn from others’ mistakes. For example, TGOD tripled its HVAC capacity after seeing reports of other licensed producers (LPs) struggling with humidity control. The Mississauga company also almost doubled the size of its processing facilities to accommodate the volume of flower it will be producing after seeing market bottlenecks in that area.

“So, we added more capital, we pushed back our timings, and I think that’s part of the … second-mover advantage because we were able to learn from everyone else,” Athaide says. “On the other hand, we haven’t really lost anything by not having that first-mover advantage on flower and oil because the rules around packaging are very strict. … So no one’s really built a brand of significance at this point yet.”

Feed the Soil, Not the Plants

The company’s Valleyfield facility, its flagship, was still in the first construction phase before the company announced financial restructuring plans on Oct. 18. The Ancaster facility received final production approval from Health Canada on Oct. 16, allowing TGOD to move plants from the nursery/vegetation space into the hybrid greenhouses for full flowering. (TGOD had been using a few of those vegetation rooms to flower crops for its medical patients and to supply the Ontario Cannabis Store (OCS) with organic product.)

A room without plants, however, is the best way for visitors to grasp the intricacies of scaling organic cannabis. “Our facilities are purpose-built,” Athaide says.

Take the containers in which flowering plants will sit: Each room houses 1,450 pots filled with Bernard-Perron’s living soil blend. The pots had to be custom-made to fit perfectly in the company’s mobile tables, another custom-designed piece of equipment. Those two features combined allow TGOD to grow 5,800 plants in a single room, Bernard-Perron says.

The team took an unconventional approach to controlling how air circulates in those rooms. Instead of having fans above the canopy pushing air across the tops of its crops, “we have an air-vent system that will blow air from underneath and then that air moves through the canopy of the plant and then cools the leaf surface from underneath,” Bernard-Perron says. This system also allows the cultivation team to supplement with CO2 near the root zone and carry away excess moisture from deep within the canopy. “Then we exhaust it through the centralized air filtration system and then outside. So we get rid of the smell, and it’s the most efficient way to cool our product,” he adds.

Managing temperatures in a greenhouse with such a heat-sensitive crop is a significant challenge during Canadian summers, when outdoor temperatures can spike well above average to 100 degrees Fahrenheit. Operating at such a northern latitude also means TGOD needs supplemental lights to cultivate year-round. To solve the latter problem without exacerbating the former one, the company opted for LEDs. “Those lights are actually the closest spectrum we can find to natural sunlight,” Bernard-Perron explains, “and we have a better penetration inside a canopy, we use less energy, [so] we don’t have to cool as much to be able to have our target light level on our crop.” The company is studying how those fixtures affect the crops’ phytochemistry and yield and hopes to have results in 2020.

More important than lighting is the company’s living soil program. A living soil, Bernard-Perron describes, is “soil in which we have brought back the natural process that you can find in nature. … We’re using a lot of beneficial microbes, bacteria, fungi, beneficial insects, nematodes, that all work together to transform the organic fertilizer we’re putting into the soil into living nutrients and to plant-available forms. So, we’re basically feeding the soil that then feeds the plants.”

“What the plants do in exchange for the soil is take CO2 from the air, use the sunlight to photosynthesize and transform that into sugar that they then push back into the soil,” Bernard-Perron says. “The plant is basically sweating sugar into the soil that feeds those beneficial micro-organisms. So, you have this awesome, built-in feedback loop that is your living soil system.”

In addition to lighting, the company is also studying how its organic cultivation approach impacts yields and plant chemistry. (Although more studies are needed, early data shows higher cannabinoid and terpene content, says Bernard-Perron.)

That soil’s microbiological diversity is also the company’s first line of defense in its integrated pest management (IPM) program. “Every handful of soil that we pick up [has] literally tens of thousands of kilometers of fungal network, fungal ivy, that are connecting the soil, the bacteria, and the plants and acting as a line of defense against other [predatory] micro-organisms,” Bernard-Perron says. “There’s so many good micro-organisms that are competing with everything and want to keep the plant healthy because the plants are giving them sugar. So they have to keep up their wall and keep pathogens outside.”

Organic Talk

Communicating these organic concepts to consumers is easier said than done, says TGOD’s head of marketing. But the slower market rollout gave the company more time to build its identity—or, as Campbell puts it, find its “story.” And that story is rooted in organics itself.

“Organic isn’t an adjective,” Campbell explains. “Organic is a fundamentally different consumer habit, [where] people now want to have transparency about where their products are coming from and what goes into [them].”

The Canadian market is fairly knowledgeable about what an organic certification means, and a large segment seeks out that certification in their produce, Athaide says. “Half of Canadian consumers buy something organic on a weekly basis, about 30% try to buy organic or kind of healthier products whenever they can,” he says. “[Public relations firm] Hill+Knowlton did a study earlier this year and found that 61% of medical patients and 50% of recreational consumers would prefer organic cannabis.”

While awaiting further test results on the effect the organic program has on TGOD’s yields and phytochemistry, education is focused on making the connection between cannabis and things people know: soil-grown, organic nutrients, no pesticides. That messaging gets out mainly through budtender education.

“We’ve launched a proprietary organic certification program for budtenders, educating [them] exactly on what is the difference between organic and non-organic growing,” Campbell says. “We want the first question for a budtender to ask when somebody goes in-store to be, ‘Would you prefer organic?’ If that is a starting point for our conversation, to make people aware that there is a difference between organic and non-organic cannabis, that’s a great differentiator for us and for a budtender to guide somebody towards our brand.”

Sustainability-Driven

TGOD’s sustainability initiatives also play a big part in the company’s identity and messaging.

“Our tagline of ‘making life better’ might sound simple, but that’s really what we’re doing,” Campbell says. “On the consumer end, we’re delivering a certified organic product to individuals. … [But] making life better is, beyond just cannabis, how are we improving things? … Improving our legacy on our neighbors, our friends and our generations to come is something we take extremely seriously.”

Being as sustainable as possible permeates nearly every decision the company makes. For example, TGOD packaging is mostly glass. Not only is glass packaging 100% recyclable and avoids static cling (which can cause trichomes to stick to the sides of plastic containers), TGOD also uses its containers as marketing tools by posting videos on how to reuse them to grow herbs or repurpose them as organizational tools. In addition to the original content, that sustainability angle “gives us a bit of a leg up on some of the competition because we can talk about all those things that we are doing for the environment,” Campbell says.

Those environmental initiatives aren’t limited to containers. The company designed both of its facilities to be LEED-certified by the Canada Green Building Council pending finalization of construction and operations. LEED stands for leadership in energy and environmental design. It’s a widely known rating system for green buildings around the world, says Karine Cousineau, TGOD’s director of government relations and sustainability.

In addition to the sustainable materials used to build the facilities, the Ancaster site is decked with solar panels and a co-generation system that produces electricity to reduce the company’s load on the local power grid. The natural gas system also serves as a CO2 generator for the greenhouses and a heating source during the winter to keep the open-air rainwater basin from freezing. Any excess heat can also be shared with neighboring farms.

The TGOD team also collects an impressive amount of data, all processed by a centralized artificial intelligence system that will find efficiencies. Once fully built out, “there’ll be thousands, if not tens of thousands, of different sensors within these facilities that will track everything from external weather and environmental conditions to the movement of the plants internally to the soil conditions, the humidity, the lighting, and things that are happening down at a leaf level of a plant [through hyperspectral imagery],” says Geoff Riggs, TGOD’s chief information officer.

“All of that will be synthesized together into a very sophisticated data management platform, which then yields very novel and unique analytical insights,” he adds. It’s hard for Riggs to point to any one particular data set he’s eager to examine because, he says, “it’s not necessarily one set of data that’s most exciting—it’s the ability to combine all those different data sets to produce very interesting analytical observations.”While some individuals and companies may look at sustainability from a purely environmental perspective, TGOD sees it as much more than that. “It’s also the whole social side of things and governance,” Cousineau says. To that end, she and her team are working on a survey “where basically we work with our stakeholders to determine: What should be the most important for TGOD? What should we track? What kind of KPIs [key performance indicators] should we put in place?” And at TGOD, stakeholder is a broadly inclusive term. The company not only sends surveys to management, “but also every stakeholder we have, from neighbors, employees, legislators, customers, consumers,” she continues, the goal being to have everyone “be part of what we’re building.”

Striving for Long-Term Stability

Despite the company’s best efforts, slow retail licensing has dampened the legal market and kept the illicit market alive and well, according to Athaide. This caused market investors to pull investments across the board, sending cannabis stocks tumbling and shrinking the ability for cannabis companies to raise capital. TGOD announced a review of alternative financing options on Oct. 9, following a change of terms from banking partners. TGOD’s shares went into a tailspin. As of Oct. 22, the company’s stock was trading at CA$1.09 on the Toronto Stock Exchange, down from its September 2018 high of CA$8.25.

Despite TGOD receiving final approval from Health Canada to commence full cultivation operations in the Ancaster facility, the company decided to scale back its production, citing those market forces out of its control. Ancaster’s production goal for 2020 is 12,000 kilograms (~26,455 lbs.) of cannabis (slightly below its full capacity of 17,500 kg (~38,580 lbs.)) as part of the company’s financial restructuring to maintain profitability by Q2 2020, the company said in an Oct. 18 release.

The Valleyfield buildout also is ramping down; the company expects to produce 10,000 kg (~22,046 lbs.)—Phase 1A originally was slated to yield 65,000 kg of cannabis annually, with Phase 1B doubling that capacity. The site’s processing facility also is on hold, and all product from Valleyfield will be processed and packaged at Ancaster. The company estimates that it will need $70 million to $80 million by the end of Q2 2020 to undertake the plan and reach positive operational cash flow, it said in the same release.

“With the current Canadian legal market being smaller than initially anticipated, mainly due to a slow rollout of retail locations in key provinces, we believe that our revised plan will allow TGOD to right size its production to capture the organic segment, while maintaining optionality to quickly accelerate and expand as more retail locations begin to open,” added Athaide in the statement.

To avoid being at the mercy of a single market’s shifts and woes, Athaide has an eye on a future where TGOD is in multiple markets. “Our vision is to be the largest organic cannabis and hemp brand globally,” he says. “Our strategy is not to be fully vertically integrated into everything. We are doing the organic cultivation in Canada. We have developed the IP, but as we go international, we’re finding great partners. … Like, for instance, in Poland ... we’re buying third-party organic hemp [for our hemp business] where we’re then drying it, extracting it, creating it into oil.”

Along with Poland, TGOD has operations or agreements with groups in the U.S., Jamaica, Denmark and Mexico. In each of those, “we’ve chosen those parts of the value chain that we believe we can uniquely own and add and do better than anybody else,” Athaide says. “You can be good at a lot of things, you can’t be great at everything. So we’re focusing on those parts that we can be great at and finding great partners for the rest.”

That said, the company’s financial struggles make it difficult for TGOD to focus on international expansion—it doesn’t make sense to spend capital on satellites when the core business isn’t as solidified as it should be. But Cannabis 2.0, Canada’s legal launch of extracted products, has the CEO hopeful. “We have a best-in-class science team that is not only looking at clinical research, but also applied science to help differentiate our products. They have been instrumental in developing our product portfolio for Cannabis 2.0, working closely with other teams on formulations. I am excited about the upcoming launch of our organic teas, infusers and vapes in mid-December,” Athaide says.