Of all the nutrients provided by growers to stimulate plant growth, nitrogen (N) is needed in the largest quantity.

Thus, meeting the N needs of cannabis is central to developing a successful fertilization strategy. Because of the volumetric importance of N, it is not surprising that symptoms of N deficiencies often are the first to manifest during production and are the most common plant health issue growers see. Symptoms of N deficiencies that cannabis plants can exhibit include pale green lower leaves and lower leaf yellowing, and as symptoms progress, necrosis and plant stunting. All of these symptoms occur when the available N supply is inadequate. Symptoms develop on the lower leaves because N is a mobile element. Plants will move (translocate) N from the lower leaves to the growing tip if inadequate levels are provided. On the opposite end of the spectrum, when N levels are excessive, lower leaf marginal necrosis (burn) occurs.

Nitrogen Management

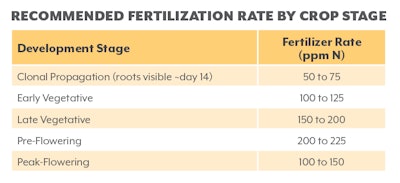

The concentration of nitrogen plants need corresponds with where the plant is in its development. Here are the N needs of cannabis plants for each life stage, from rooting to flowering.

Rooting

When plants are being propagated as clones, the nutrient reserves in the cutting can be leached out easily with mist or fog. Nutrient reserves could further be depleted if the cutting was taken from an old mother plant, as reserves in stock/mother plants also diminish over time. As such, it is important to supply a dose of essential nutrients to the cuttings to restore the nutrient reserves. Once roots are visible, provide the plants with 50 ppm to 75 ppm of N two to three times per week to help restore the nutrient levels within the cuttings.

Transplant

Smaller clones just transplanted into a container primarily are putting their energy into establishing a root system. Therefore, they require lower levels of N, so beginning a constant liquid fertilization program of 100 ppm to 125 ppm N will help jump-start growth.

Vegetative Fill Out and Pre-Flowering

Once the roots have reached the edge of the pot and the root system has developed, the plant will start producing vegetative growth. During periods of rapid vegetative growth, cannabis plants require a higher concentration of N, so initially you can ramp up N to 150 ppm to 200 ppm for every feeding during the vegetative stage, and then 200 ppm to 225 ppm of N can be used for feedings during the pre-flowering stage. This will help ensure that adequate levels of N are provided as the plant bulks up.

Flowering

As with any plant that has terminal flowers (including poinsettias and chrysanthemums), the nutrient demands of a cannabis plant peaks and then decreases throughout the flower period. This makes sense: If the plant is not growing as rapidly, as one can easily measure by the change in plant dry weight, then the amount of N supplied should be dialed back. Thus, a lower level of 100 ppm to 150 ppm of N should be applied at every feeding during peak flowering.

Conducting in-house monitoring of the electrical conductivity (EC) in the substrate (as discussed in the “Nutrient Matters” article in the April issue of Cannabis Business Times) will help ensure that the nutrient levels are adequate, and not limiting or excessive.

Corrective Procedures

A straightforward procedure exists to correct an N deficiency: Simply increase the N supply for one or two applications to help restore the N reserves in the plant. Applying 300 ppm to 400 ppm of N from a balanced fertilizer such as 13-2-13 Cal-Mag will provide all the essential nutrients to the plant. Other alternative complete fertilizers include 17-4-17 Cal-Mag, 17-5-17 Cal-Mag, or 15-5-15 Cal-Mag.

Another option to consider is a dark-weather feed (15-0-15) if only N, potassium (K), and calcium (Ca) are desired. If a higher ammoniacal nitrogen (NH4-N) concentration and higher phosphorus concentration are desired to boost vegetative growth and fill out, then a fertilizer such as 20-10-20 can be applied. Apply these corrective procedures as a 10-percent flow-through leaching irrigation if the plants are grown in pots. This will stop the progression of deficiency symptoms, but will not reverse any severely affected chlorotic or necrotic leaves.

Having a balanced fertility program at the target N levels during each stage of production will help ensure that your cannabis plants have adequate nutrients and will help avoid the development of lower leaf yellowing.