Each element of Connecticut Pharmaceutical Solutions’ production system works in sequence to produce top-shelf cannabis, aka ‘fire.’ No excuses, no exceptions. Excuses and exceptions produce schwag, and that’s not for us. But how do you make fire—all the time? Believe it or not, it’s not hard. Your production process simply must be consistently perfect. The concept of ensuring consistent perfection is called process validation.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines process validation as “the collection and evaluation of data, from the process design phase throughout production, which establishes scientific evidence that a process is capable of consistently delivering quality product.”

Here are the six concepts we focus on to produce consistent fire.

What Materials Have We Started With?

TIP: Audit your suppliers. As appropriate, we audit our suppliers. In each and every case, every process input arrives with its certificate of analysis (COA) or equivalent quality assurance (QA) that the ingredient is pure and appropriate for our purpose.

TIP: Require your suppliers to document that each ingredient is precisely what it is supposed to be and exactly what you ordered. No bait and switch, no nonsense.

TIP: Inspect all inputs. Once ingredients arrive, we visually inspect the exterior packaging for damage. We evaluate the interior contents, too. Often, we pull a laboratory sample for identity and purity testing. We check the results against the COA and our internal quality specifications to ensure the ingredient will work in our process.

TIP: Always keep a retained sample of the ingredient on file and archive all testing records and COAs indefinitely.

What Do We Do?

TIP: Document frequently. We document what every production employee is supposed to do, and each employee documents what they do each time they do it to track any deviations from protocol. In addition to making the product, production operators are responsible for completing and documenting production process quality checks every half hour. Quality control (QC) analysts inspect that same production, perhaps every two hours, and document their findings. A QA analyst is responsible for providing the batch records and documents that detail what each employee is supposed to do during each process and inspection step. QA analysts also check production, perhaps every four hours.

TIP: Complete routine evaluations and inspections during the work-in-process (WIP) steps to assure you will not see any surprises by the time you reach your final products. As our product moves through our production process, it is called WIP. WIP is production inventory that is no longer included in raw materials inventory, but is not yet a completed product.

Equipment Qualification: IQ, OQ, and PQ

Process validation does not stop with employees, ingredients and production checks. Our manufacturing processes rely on certain production equipment, so we are obligated to assure that the equipment is appropriate for its intended use.

TIP: Equipment specifications should be met after installation, across different operators and through repeated performance. Installation qualification (IQ), operational qualification (OQ) and performance qualification (PQ) are well-worn words in the production of FDA-regulated foods, drugs and cosmetics. IQ, OQ and PQ are used to ensure that all systems, both mechanical and software, meet their specifications and fulfill their intended purposes.

TIP: From the equipment validation, develop written procedures to inform operators of the equipment’s appropriate operation, maintenance and cleaning.

Process Qualification

TIP: Train your employees on the process. Changes in operators across the production system should never impact the final product. The purpose of process validation is to ensure that the entire (documented) process—with its checks on incoming materials, equipment IQ/OQ/PQ, operators, quality control and quality assurance—is appropriate for its intended purpose: to produce quality product every time that we go through the process.

TIP: After each process run, archive all activities and measurements. A good result (finished product) should not be a surprise that pops up out of a mysterious process. Instead, a good result should be one that could not have been avoided given the intermediate results for which we tested and which we found along the course of the production process.

Batch Testing

TIP: Make sure that your sampling techniques are adequate to ensure, for testing purposes, that your product samples represent the batch. To ensure each sample is representative, you can sample the four corners of your plant and the middle, or you might test the top, bottom and middle in 10 places in the room. If you only take the tops, you might get overly strong results, and if you only sample from the bottom, you might get overly weak results. At the end of the production process, each product batch gets final-product tested before it’s released.

TIP: Use both internal and third-party testing to validate products. We work hard on all batches, and we have set expectations for them. Therefore, we use internal testing and external third-party testing to ensure that we are on the right course as we produce every batch. Any surprises, high or low, cause us pain. A 24-percent strain that tests at 32 percent or 16 percent sends us into root-cause analysis: What went wrong?

TIP: Lab technicians are not yet perfect, so discuss with them their sampling and testing techniques to avoid inaccurate results, whether too high or too low. We know that we must be as careful with our own sampling techniques as we are with our production methods. The same concepts apply to the work of our third-party lab. Apart from the characteristics of our products, the lab’s sampling and testing techniques can introduce clear error.

Retained Samples

TIP: Retain samples of your products and undertake stability studies (what happens over time and under various conditions) with them. For example, we look at what happens to our product in its packaging if it sits in a car for a month during the summer. Is that different from what happens over 30 days during winter? We do not expect to learn about this from one of our patients. We do the work ourselves—with the help of our third-party lab—document the results, and keep the samples for a long time to avoid any surprises. (We still have samples from our first batch in December 2014.) If someone were to raise a legal claim about our batch 5678, we will have a retained sample on hand. While some chemical compounds of the sample (especially of flower) may have changed over time (and that is something we study as well), the product would still maintain any heavy metals or pesticide residues claimed to be present.

Pop the Dom

TIP: Before reaching for the Dom Pérignon to celebrate your next harvest, make sure that you followed Dom’s example throughout your entire process. Dom Pérignon may not have invented bubbly wine, nor even the méthode champenoise, but he did study the méthode champenoise process of secondary fermentation of already-bottled wine. He recorded his methods and results, made significant process and packaging improvements and, as a result, had far greater success than his predecessors in producing and marketing exactly what he had intended to produce and market. He did not know about ‘fire’ cannabis, but he said, “Come quickly! I am tasting the stars!” For the 1600s, we’d say his results were pretty darn good.

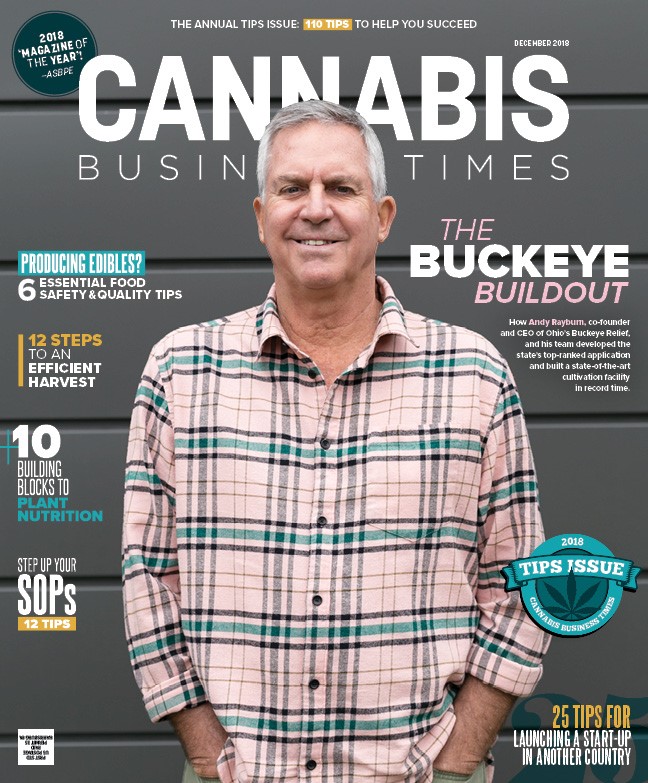

Explore the December 2018 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find you next story to read.

Latest from Cannabis Business Times

- Cannabis Industry Reacts to Biden’s Rescheduling Announcement

- As Predicted, 4/20 Sales Surged During Cannabis Industry Holiday Weekend

- DEA 2024 Report Focuses on THC Potency, Organized Crime, Youth Edible Consumption

- Nature's Miracle, Agrify Sign Definitive Merger Agreement

- 5 Things to Confirm When Signing a Cannabis Facility Construction Agreement

- Ziel Partners With Portocanna, Receives 1st EU GMP Certification for Microbial Control Technology in Cannabis

- White House Moves to Reschedule Cannabis in ‘Monumental’ Decision, Biden Says

- SOMAÍ Group, and Its Subsidiary, RPK Biopharma Expand Cookies Partnership to Include Europe and the UK