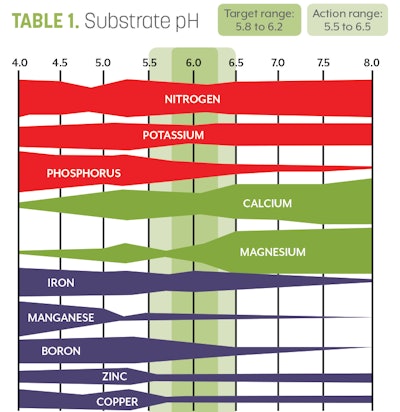

Fertility management can be challenging for many crops. Multiple steps and variables can occur along the fertility chain between plumbing and plant. For example, you may be providing enough iron (Fe) to your plants, but due to a higher or more alkaline pH of your growing substrate, that iron may not be available to the plant.

To ensure you provide plants the required fertility, a nutrient monitoring program should be implemented. One of the most useful nutrient monitoring techniques is the PourThru method, which allows growers to analyze the solution in the plant container and to troubleshoot potential problems by displacing a small portion of the solution in the plant container for analysis. This leachate will then be analyzed for pH and electrical conductivity (EC). These two metrics reveal the total quantity of dissolved fertilizer ions in the pot solution (EC) and how those ions will be available to the plant (pH).

How It Works

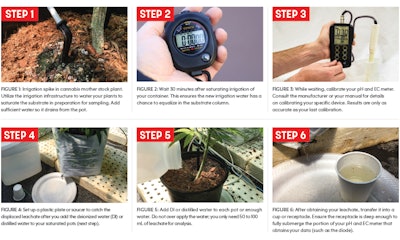

The PourThru nutrient monitoring system consists of eight simple steps.

1. Irrigate the crop. In order to displace some of the solution within the pot, there must be sufficient liquid in the pot so that when you add more, a small portion of the liquid leaches out. To complete this step, irrigate your plants thoroughly so they are almost saturated (Fig. 1).

It is important that your monitoring program includes about three to five plants per zone in your greenhouse or indoor operation. A zone is defined as a distinct region, climate or growing condition. Zones or units could also be composed of different cultivars. For example, if you have a cultivar that produces a lot of biomass and another cultivar that is more compact, you would want to sample each cultivar separately to ensure that each crop is being provided the nutrients it needs. The smaller cultivar could have a higher EC due to a lower use of fertilizer ions, while the larger cultivar could experience nutrient shortages due to more biomass production.

2. Let the irrigation solution settle. After irrigating your crops, allow the solution to settle for about 30 minutes so the added solution distributes in the pot. Think of this step as letting the solution equalize throughout the pot. When you irrigate, you are applying a greater concentration of ions to the pot. The solution in the pot has a lesser concentration of ions due to plant uptake. By waiting after irrigation, you allow the new ions to evenly distribute through the pot profile. This step ensures an accurate reading (Fig. 2).

3. Calibrate your meter. Next, calibrate your pH and EC meter. The readings are only as accurate as your last meter calibration. Many meters are available on the market; however, any meter you purchase should have both a pH and EC function. Consult your manufacturer or your manual for instructions on how to calibrate the instrument (Fig. 3).

4. Place a saucer underneath. You will need to place something under your containers, such as a plastic plate or a houseplant saucer, to catch the solution you will displace from the pot. The saucer should be able to hold 100 mL to 200 mL of solution. For analysis, you will need 50 mL to 100 mL of solution, so ensure your saucer has a greater capacity than what you need (Fig. 4).

5. Apply more liquid to your pot. The pot should already be saturated, and the solution equalized through the container profile. When you add more liquid to the pot, a small volume of the container solution will be displaced. Use deionized water (DI) or distilled water if your irrigation water is not pure. This ensures that the solution you are adding to the container does not contaminate the results. Add 200 mL to 500 mL of DI or distilled water per container. Larger pots may require more solution. For larger or odd-shaped containers, add 100 mL of liquid at a time until enough leachate is obtained (50 mL to 100 mL) (Fig. 5).

6. Collect the leachate. Next, you will obtain your leachate sample for analysis. There should be a small amount of displaced liquid from the container in the plate or saucer. Again, you will need about 50 mL to 100 mL of solution for an accurate reading. Collect the solution in a cup or container large enough to submerge the diode on your pH/EC meter. Do not lose or discard this solution before you are done, as you will analyze it in the next steps (Fig. 6).

7. Analyze your leachate. Now that you have the leachate in a cup or container, it is time to analyze it. Follow the instructions on your meter to obtain both your pH and EC measurement. For the most accurate results, ensure the numbers on your meter reach a stable reading (Fig. 7).

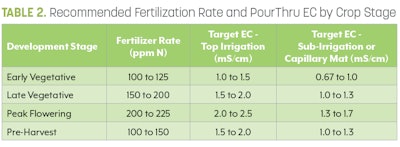

8. Interpret your results. You should have two numbers from your unit. The first will be a pH reading. The optimal pH for cannabis can be found in Table 1. The optimal EC for cannabis can be found in Table 2.

Corrective Procedures

Before making any corrective measures, determine if the values are outside of the acceptable ranges (Tables 1 and 2). If the EC or pH values have drifted out of the acceptable range, then take corrective measures to ensure that the fertility program is back on track.

For strategies to correct low and high pH, see the article, “New Research Results: Optimal pH for Cannabis,” by Brian Whipker, James T. Smith, Paul Cockson and Hunter Landis in Cannabis Business Times’ March 2019 issue.

To learn how solution and substrate EC can be used to enhance cannabis growth, see “Optimizing Electrical Conductivity (EC)” in Cannabis Business Times April 2019 issue.

As always, remember to recheck your substrate pH and EC within a few days to determine if reapplications are needed.

Summary

By monitoring your pH and EC through a PourThru program, you will be able to catch nutrient accumulations before they become an issue. This will not only save you time but will also allow you to provide nutrients in a more precise and economical fashion.

Brian Whipker, Paul Cockson, James Turner Smith & Hunter Landis are from the Department of Horticultural Science, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, N.C.