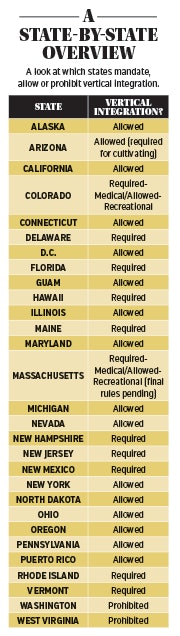

As more medical and recreational states come online and the cannabis industry matures, regulations and opinions about vertical integration are evolving rapidly. The changing landscapes in individual states and across the industry greatly influence individual perspectives on whether cultivators should be mandated, permitted or prohibited from also operating a dispensary.

Cannabis Business Times reached out to individuals involved in key aspects of the industry, from policymakers to retailers and cultivators, for insights on vertical integration in cannabis and what may lie ahead.

Insights from … Brian Vicente

Partner and founding member of the law firm Vicente Sederberg LLC, principal at VS Strategies, and executive director of Sensible Colorado

Vicente’s extensive contributions to marijuana policy reform include close involvement with Colorado’s regulatory structures. Leading up to 2010, when the state became the first to regulate and license medical marijuana businesses (several other states had legalized medical marijuana use, but did not issue business licenses), with a program that mandates vertical integration, Vicente was part of the governor’s advisory task force. Later, he was one of the primary authors of Colorado’s Amendment 64, which legalized adult-use recreational marijuana in the state in 2012. Amendment 64 allows, but doesn’t require, vertical integration for recreational businesses. Vicente views mandated vertical integration—which continues to apply to medical marijuana in Colorado—as a valid approach that still bears merit. “In 2010, we were essentially working from scratch to create the regulatory structure,” he recalls. “There was a real feeling that we needed some degree of tight controls at the beginning.” The primary argument, echoed in many states regulating marijuana for the first time, was the need to limit the number of people being overseen. Vicente believes Colorado’s robust industry, solid patient access and ability to adjust its stance for recreational businesses affirms the policy worked.

Vicente acknowledges mandated vertical integration has drawbacks, particularly as it affects industry diversity. “Vertical integration is a heavy lift. It’s very expensive to open both a grow and a store,” he says. “By mandating that anyone that’s allowed to do either of those activities needs to own both, you’re basically limiting yourself to rich people that can enter the market. I think that’s a negative thing in terms of promoting economic and racial diversity in this new industry.”

An added disadvantage is a potential lack of specialization. “With mandated vertical integration, you’re essentially requiring farmers to also be retailers, or retailers to also be farmers. Those are two specialized skill sets,” Vicente says. By allowing farmers to be farmers, he believes better products may result.

Vicente predicts new medical states will continue to heavily regulate cannabis through mandated vertical integration and limited licensing. “I think vertical integration probably does make sense in the short term, but as these programs expand and the regulators become more sophisticated in tracking the parties involved, I think that need for required vertical integration is certainly going away.”

Insights from …Ramsey Hamide

Owner of Main Street Marijuana in Vancouver, Wash.

As a retailer in a state that prohibits vertical integration—and makes all production, sales and tax-related data public record—Hamide has a unique perspective on this issue. His flagship Vancouver store, now one of three locations, is Washington’s top-grossing retailer with more than $44 million in sales over the last three years, according to 502data.com. Main Street cannot produce any of the products it sells.

Hamide says consumers are the clear winners under Washington’s regulatory structure. Rather than vertically integrated businesses incentivized to sell their own product, consumers find responsive retailers instead. “We have, I believe, 1,600 different SKUs on our shelves as of today,” he explains. “In Washington, we have by far the most advanced, consumer-friendly market in America, and it’s a result of that lack of vertical integration.”

In the beginning, Washington’s prohibition created what Hamide describes as an “us versus them” dynamic between retailers and growers. He responded by building relationships with processors to develop products, price points and packaging his customers want. “We have [more than 1,200] licensed producer/processors competing in an ever-increasingly competitive environment. My job is to steer the ones that want to work collaboratively to understand the end consumer, because they are separated from our customers,” he explains.

One of the biggest advantages Hamide sees in markets with vertical integration is that vertically integrated retailers can acquire product at cheaper price points and drive down costs. A benefit for production facilities is that there are tax deductions available to them that aren’t available to retailers [under IRS tax code 280E], he adds. “For the stores, it hits us hard not being able to take any deductions and then not being able to produce anything we sell,” he says.

For this reason, Hamide would seize the chance if vertical integration became an option in Washington. “Because of the customer base we now have, we would definitely be vertically integrated, and that would be just as a service to our customer to try to drive down the product cost even further,” he says. “If we could, we would, but we wouldn’t stray from what’s made us the No. 1 store in Washington. That’s having the best product selection and the best prices.”

Insights from … Jason Boyer

Manager and grower at Wild West Growers in Eugene, Ore.

Wild West Growers could have full vertical integration under Oregon law, but the growers collective chooses to leave retail to others. The group has producers’ licenses to grow cannabis, a processing license to process edibles and extracts, and a wholesale license that allows for distribution, but it stops there. Future plans don’t include retail stores. While some Oregon growers integrate through retail, single license holders are common. Boyer says his group is somewhat unusual in that it has multiple licenses. He believes that degree of choice under Oregon’s system fuels free commerce and results in better product. “I don’t feel vertical integration should be mandated,” Boyer says. “The Oregon strategy leaves it up to the market to decide what fails or survives as a business model.”

Boyer also sees a lack of specialization as a major disadvantage under forced vertical integration, which he believes leads to bulk, middle-spectrum product instead of high-end cannabis. “What we view as our specialty, which is growing cannabis and processing it into edibles and extracts, allows us to create the highest quality we can, work on the efficiencies of our business model, and try to create a sustainable model,” he explains.

Boyer feels that specialization possible with optional vertical integration is good for the industry. He believes higher-quality products, better user experiences and improved safety for consumers result. “I think Oregon got it right,” he says. “I think this is better for the market. New users who try cannabis for the first time will have a better experience with it [due to the higher quality], which will just add to the user group.”

Insights from … Ben Kovler

Founder, chairman and CEO of Illinois-based Green Thumb Industries (GTI)

In leading a company that currently holds licenses in Illinois, Nevada, Massachusetts, Maryland and Pennsylvania, Kovler deals with regulatory structures that vary from mandated vertical integration to more permissive approaches. He feels a key element in vertical integration is whether the market allows for a wholesale business.

“Massachusetts, for example, is forced vertical integration. There’s no wholesale market in Massachusetts right now, but that’s coming,” Kovler says. Other GTI markets permit optional integration with a wholesale component. He notes that Pennsylvania, where vertical integration is allowed, uses the acronym VIP (Vertically Integrated Permittee) to describe the small number of licensees who have been awarded both cultivation and dispensary licenses.

One advantage to vertical integration in Kovler’s eyes is the access growers have to consumers. “We certainly are more in touch with the patients and the consumer on the retail side. That’s given us some insight into tastes and preferences of the patients and consumers. That can drive innovation, ... R&D on the other side,” he says.

However, Kovler also sees hurdles for vertically integrated businesses. “Operating in the cannabis space is very difficult. The challenge here is often ... misunderstood,” he says. While he understands the thinking that more is better, he also sees the number of licenses in markets regularly exceed the number of open businesses. “It’s executing. Execution is the hardest thing in our business,” he says.

Kovler thinks mandatory vertical integration will soon be obsolete. “We’re in the mature part of Cannabis 2.0, and we’re starting to see forced vertical integration being phased out,” he explains. He points to a “wave of states” regulating in new ways, such as limited numbers of licenses, that allow for tight regulation without mandatory vertical integration. He believes this will promote greater opportunity and innovation, as well as lower prices and more access ahead.

Insights from … State Sen. Roger Katz

Chairman of Maine’s Committee on Marijuana Legalization Implementation

A 2016 citizen’s initiative referendum legalized recreational/adult-use marijuana in Maine. Senator Katz is chair of the legislative committee tasked with creating the laws that will regulate and oversee the state’s new recreational industry. Committee members have examined other state models thoroughly. Their recommendations may provide insight into the future of vertical-integration mandates in the cannabis industry.

Maine’s medical marijuana laws, in place since 1999, require vertical integration. However, Sen. Katz reports that a recreational bill being drafted now [late August 2017], does not include that requirement. “I can’t speak to why the original medical law required vertical integration, but, at least in the draft of this bill, we have not required vertical integration, but we are allowing for [it],” he says.

Katz feels the system supports what the committee sees happening in other states and its understanding of the climate in Maine. Under the proposed bill, the state will have separate cultivation, processing and retail licenses. “A licensee could, in theory, apply for only one of the three licensees or two of them or all three of them,” he explains. “We didn’t necessarily see anything wrong with an individual or a company being involved in all three aspects of it, but we didn’t see any good reason to require it either. … The requirement would seem to favor larger businesses and larger investments, and that hasn’t been our guiding goal. We want to make it available to the little guy as well as the corporations.”

One reason behind not requiring vertical integration is the committee’s desire to open the new industry to all. “We want to draft something that is good for our rural state, and then certainly for people who want to get involved in cultivation, for instance, who maybe have no interest in either processing or retail, we want to give them a chance,” Katz explains.

At press time, Maine was slated to hold a public hearing on the committee’s bill near the end of September 2017. Then Katz hopes that a special session of the legislature in late October will see it passed. Whether the bill in its current form becomes law or not, Maine will provide one more example of how regulations and opinions on vertical integration in the cannabis industry continue to evolve.