Applicants for Illinois’ new craft grow licenses are spending hundreds of thousands of dollars in rent payments and losing contracts with experts they had lined up to help run their businesses as they wait for the state to tell them what they all want to know—whether they are among the 60 who will ultimately be awarded a license.

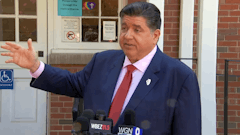

That is according to a brief filed by Irina Dashevsky and Ryan Holz, partners in Greenspoon Marder’s Cannabis Law Practice who are working on a case that has landed in the Illinois Supreme Court.

The case is one of several pieces of litigation pending in the state as officials slog through their licensing process to issue new adult-use cannabis dispensary and craft grow licenses to social equity applicants.

Illinois awarded 32 craft grow licenses last summer and was required by law to issue 60 additional craft grow licenses by Dec. 21, 2021, Dashevsky told Cannabis Business Times.

When they announced the initial 32 license winners, state officials said they would issue the next 60 licenses to members of the same applicant pool, Dashevsky added, which was not required under Illinois’ adult-use cannabis law.

“I think, in large part, that was due to the fact that everything was so delayed,” she said. “There really wasn’t a need or a point to create an entirely new, separate application process. There wasn’t time to do that or manage that or expand resources on it. And they had a strong applicant pool, so that’s what they put forth.”

Relying on that update from the state, Dashevsky said 1837 Craft Grow LLC, one of the craft grow applicants that was not awarded one of the initial 32 licenses, reorganized its business to maintain real estate and wait until the next 60 licenses were awarded by Dec. 21.

“That meant paying for an option to extend the closing date on the real estate that they had been holding this entire time, and generally keeping pause on everything,” Dashevsky said. “It wasn’t always that you don’t have a shot. It was, ‘Hey, in the next couple months, you’ll find out about the next 60.’ They’re a very strong group with a strong application, so there’s some confidence that there’s a good chance they could be one of the next 60 winners.”

But due to litigation from 13 applicants who were disqualified during this licensing round, those next 60 winners were not announced in December, and have yet to be announced now, a month past the deadline.

A court has issued an indefinite stay that forbids the state from naming the winning applicants and issuing the licenses while the litigation inches its way through the legal system.

And in the meantime, Dashevsky said that 1837 is not alone in its plight.

“We have 12 other participants with very similar … damages and positions and claims, and I’m sure that there are dozens more out there, as well,” she said. “The Dec. 21 deadline came and went, and many teams who applied relied on that deadline [and] set up their real estate or other businesses with the notion that they would know one way or the other by Dec. 21. And so, this is just exacerbating an already tough and harmful situation and adding on to those damages.”

Now, a month past the Dec. 21 deadline, many craft grow applicants who have been able to retain their real estate have held onto it for two years, since the start of the application process, Dashevsky said. Other businesses have paid out a hundred thousand dollars in rent payments only to eventually lose the real estate anyway as they wait for licenses to be issued, she added.

“And those like 1837 are negotiating extensions, paying for extensions [and] paying for options,” Dashevsky said. “And that’s a critical [issue] because [having real estate] was a requirement of the application and really a requirement to ramp up this new business. So, losing real estate and starting from scratch, you’re going to be that farther behind the other craft grows as well as cultivation centers in coming to market.”

Applicants also risk losing contracts with industry talent and experts as the licensing dispute drags on.

“In time, they had to move onto other ventures,” Dashevsky said. “The other side of that coin is other people have foregone other ventures and opportunities as they wait. So, there are damages on both sides of that.”

In addition, some applicants face a loss of investor commitment now that the licensing deadline has come and gone.

“Those who had investors lined up from early 2020, and even in this very specific case [with 1837]—many were telling their investors, ‘Hey, we’ll know by Dec. 21.’ And when you don’t, the investor leaves the pool and says, ‘Hey, I’m going to go elsewhere, this has been a mess,’” Dashevsky said.

“These are critical losses that are going to be hard … to make up even if they get a license,” Holz added. “They’re basically starting from scratch.”

Now, 1837 is asking the Illinois Supreme Court to let the state name the winners of the craft grow licenses so that it and other applicants can move forward.

“We’re expecting a ruling from the Illinois Supreme Court in short order, hopefully before the end of January,” Holz said, adding that the state’s highest court could at least allow the state to name 47 of the license winners while the litigation concerning the 13 disqualified applicants progresses.

“Obviously, if the Supreme Court came down and allowed them to announce at least 47 of these licenses and allow 47 people to understand that they’re in line to get a license, it would also allow other people who are not among those 47 to perhaps reassess their options and their chances of getting a license,” he said.

Without relief from the Supreme Court, Holz said the litigation could “drag on for quite a while.” The next court date in the underlying case regarding the disqualified applicants isn’t scheduled until March 10.

“And I think it’s optimistic to think that those cases will be resolved on March 10,” he said. “I think it’s very optimistic. So, you will have longtail litigation here going into the summer, perhaps even into the fall/winter, depending on how these cases play out, where you will get no movement on the 60 craft grow licenses that are out there.”

Any sort of court order regarding the pending litigation must be narrowly tailored, Dashevsky added, and she and Holz argue that the stay on naming the license winners is not.

“There are 13 licenses that are really at issue out of 60,” Dashevsky said. “Whether they win or don’t win their cases, at most, we’re talking about 13. So, the fact that 47 other licenses are being implicated and held up as a result of 13 disqualified applicants trying to prove that they weren’t disqualified—if you’re balancing the equity, this doesn’t make sense. … There’s a statutory deadline that’s been stayed. It has to be narrowly tailored to exactly what’s necessary here. And this is simply not narrowly tailored.”

In addition, Holz said, there is no recourse for these would-be craft growers as they wait for the state to name the license winners.

“There’s nobody on the other side of the rainbow with a pot of gold that’s going to pay them or give them any kind of compensation for this loss,” he said. “Every dollar that is spent to keep an option open is a dollar that’s lost.”

The longer they have to wait, the more businesses will end up giving up hope and moving on to other ventures, Holz said, which ultimately isn’t good for Illinois’ adult-use cannabis market.

“It’ll remove diversity from the market,” he said. “It will remove social equity applicants from the market. It will remove product lines from the market. So, this isn’t good for anybody that people are going to have to jump ship here, but that’s really their only other option. They either have to pay lots of money and hope this gets resolved soon and they’re successful or move on to other endeavors.”

The situation is even more unfortunate since at one point in time, Dashevsky said other states looked to Illinois as a blueprint for how to administer a social equity program in the cannabis industry. Now, she said, most states are looking to Illinois as a lesson in how not to administer a social equity program in the cannabis industry.

“I think the biggest issue is there’s a social equity component to this,” Dashevsky said. “Most of these license winners, both on the craft grow and on the dispensary side, are social equity applicants. That was Illinois’ way of trying to diversify the program and get more folks involved. It was supposed to be relatively small businesses, so they just can’t bleed like that.”

“You don’t get a lot of cases where you deal with the people involved, especially in business litigation, but there are people who are coming to us with stories, saying that ‘look, we can’t keep this going for very much longer,’ and what was a process in a revolutionary new industry that was going to open doors for a lot of people has not done that,” Holz added. “I think if you asked a lot of these folks whether they would apply again, knowing what they know, I think they would say no, and that’s kind of sad. The reality is this has jaded a lot of people."