Had he known his hands would be cuffed behind his back for possession and the intent to sell $80 worth of cannabis, maybe Tucky Blunt would have thought twice about stepping out onto the street that day.

Knowing today how fate would have it, maybe he still would have.

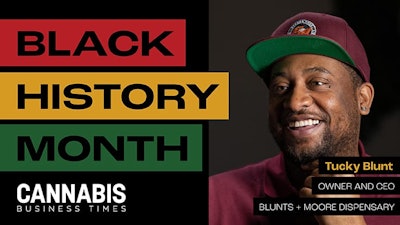

The owner and CEO of Blunts and Moore in Oakland, Calif., Alphonso “Tucky” Blunt Jr. opened the first cannabis dispensary licensed under the city’s Cannabis Equity Program when his storefront became operational in November 2018.

“I got arrested in ’05 for being snitched on, and that being snitched on allowed me to qualify to open a f---ing dispensary. How does that happen?” Blunt questioned during a recent interview with Cannabis Business Times. “It was generally meant for me to be in this space, and I never knew. I just kept doing what I thought would get me here.”

Family Heritage

Blunt is a fifth-generation Oakland native who began selling cannabis in 1996, all while maintaining a 4.0 GPA and a full-time job in high school.

Part of his family heritage, cannabis was a plant Blunt viewed as an opportunity. He never thought possessing or selling it should be criminalized, he said.

“Both of my parents sold it, but I watched how they sold it. It was never outside on a corner,” he said. “I knew early on I wanted to sell weed because I smoked it and I just knew good weed, and I knew a lot of my friends wanted weed. So, for me, it was an easy transition because everywhere I worked at, I sold weed at. Yeah, I was a 4.0 student and all of that, but I liked weed and I liked going to work because that provided me money to do what I wanted to do.”

At age 16, Blunt worked at a grocery store called Lucky’s. He had 22 co-workers and 17 of them smoked cannabis, he said.

Not only did Blunt know when all of his co-workers received their paychecks, but, from his perspective, selling cannabis during his “day job” was safer than dealing with the streets and the possibility of going to jail.

“I made more money at work than I made at work,” he said. “The only way I’m going to go to jail is if I’m going to get snitched on. If I’m on the streets, I’m snitching on myself. That’s kind of how I approached it. I always approached it as a business: sell weed but not going to jail.”

Drug War Era

While Blunt steered clear of trouble throughout his youth, growing up as a Black man during the drug war era meant having ties to those directly impacted by the injustices of prohibition. Blunt had several friends and family members go to jail for small-money drug cases, he said.

In the years following then-U.S. Sen. Joe Biden’s co-crafted and bipartisan Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, which was signed into law by President Ronald Reagan, Black people became even greater targets of stricter penalties for drug offenses.

According to the American Civil Liberties Union, the average federal drug sentence for Black people was 11% higher than for whites before the Anti-Drug Abuse Act passed in 1986. Four years after the act was enacted, which included a federal mandatory minimum sentencing provision for crack cocaine offenses, the average federal drug sentence for Black people was 49% higher.

“Coming up under D.A.R.E. [Drug Abuse Resistance Education] and the Reagan era, you know, D.A.R.E. for me was for dope—was for heroin, was for crack, was for meth,” Blunt said. “It wasn’t for cannabis. When you see the egg frying and ‘This is your brain on drugs,’ that didn’t apply for me for cannabis. We laughed at that. For me, it was more so just seeing the family split up behind a plant that’s legal now.”

Early Inspiration

Blunt said his inspiration to one day own and operate a dispensary derives from an errand he ran with his grandmother in 1999. The trip was to pick up some medicine from a dispensary at Telegraph Avenue and 19th Street in downtown Oakland, but Blunt did not know it was a dispensary while en route.

Also unbeknownst to Blunt, his grandma obtained a medical cannabis card a couple years before that trip, shortly after California became the first state to legalize medical cannabis under Proposition 215 in 1996.

“She just told me she was going to pick up some medicine. I didn’t think nothing of it,” Blunt said. “She came outside with a white bag, like, I will never forget this. She came out with a white bag. I said, ‘Granny, what’s that?’ She was like, ‘It’s weed.’ I said, ‘You bought weed out of a store?’ She was like, ‘Yeah.’ I said, ‘Oh, yeah, I need one of those [stores].’ She said, ‘Well, when you get one, I’ll be there every day of the week.’”

From that day forward, Blunt’s mission was to one day own a dispensary so he could sell cannabis legally, he said.

The day after running that errand with “Granny,” Blunt went to go get a cannabis card for himself. Within two weeks, he began working at dispensaries. With two years, he said he was growing cannabis and selling it to those dispensaries.

“So, seeing that, that there was an actual brick-and-mortar location for you to be able to come and buy cannabis—that stuck with me,” Blunt said. “At that moment, I was like, ‘I want in.’”

A Blunt Reality

Immersing himself in the environment, Blunt attempted to become a dispensary owner in 2003 but was told by various business owners in San Francisco, Hayward and Oakland that “Blacks would never own” a business in the cannabis space. His first reaction was “Why?” but he never got an answer, he said.

When Blunt applied to enter the cannabis space in 2003, he had the capital, he had a location, and he had a white business partner.

“We had all that and was just told flat out, ‘No, y’all are not going to do that. Y’all Black.’ That was my biggest hurdle, was being Black,” he said. “If we came in as a white person with that same money, I’m pretty sure I would have had a dispensary back then.”

Two years later, Blunt found himself between jobs.

It was a Thursday when he had $80 of cannabis, his medical cannabis card and a registered firearm in his trunk. He was lined up to start a new job for Alameda County, home to Oakland, the following Monday. He was hoping to become a probation officer.

But none of that mattered to a pair of police officers who arrested Blunt for possession with intent to sell that day.

“In 2005, I got told on by one of the guys I was buying weed from,” he said. “I got told on, they pulled up, told me I got snitched on, arrested me on the spot, took me downtown, I bailed out the same night, and I just went back to selling weed. The only difference is, that time I got arrested, I had actually stepped out on the turf to sell weed for the first time ever.”

Unfulfilled Mission

Rather than drag out the case, Blunt said he took a deal that included 10 years of felony probation with a “four-way” search clause, which authorizes a search of the probationer’s person, residence, vehicles and other property under his or her control.

His arresting officers were Ersie Joyner, who caught national news coverage in 2021 after enduring 22 bullet wounds during a gas station shootout in West Oakland, and Randy Wingate, with whom Blunt would later cross paths.

Still determined to learn more on the legal side of the cannabis business, Blunt attended and graduated from Oaksterdam University, dubbed “The World’s First Cannabis College,” in 2008.

But by 2013, with his mission of one day owning a dispensary unfulfilled, he decided to call it quits and stopped selling cannabis altogether, he said.

“I wasn’t getting what I wanted out of it,” Blunt said. “You’ve got to think, from ’96 to 2013, that’s a long time to be trying to do something and never see really no ramifications of it. Yeah, I went to Oaksterdam. I did little things to try to get me along the way, but I literally was just tired. I hit a wall and was like, ‘I’m never going to own, so I’m tired of selling weed.’ And I stopped.”

As Fate Would Have It

In the spring of 2017, Oakland City Council members enacted an Equity Permit Program to address disparities in the cannabis industry by prioritizing the victims of the drug war and minimizing barriers of entry into the industry.

As fate would have it, Blunt got a call from his friend Mike Marshall, who told him about the program and asked if he’d ever “caught” a cannabis case in Oakland. Thanks to being arrested in 2005, Blunt qualified for the program.

Blunt met with his business partner in September 2017, went through the license application process, was approved, ended up winning a license through a lottery in January 2018, and then he became the first operational dispensary owner under the program when Blunts and Moore cut its red ribbons in November 2018.

“Man, it was amazing,” he said about his dream becoming a reality. “To open a store in the same ZIP code where you caught a felony cannabis case in, and now you’re selling legal cannabis in that same ZIP code … it’s kind of hard to describe the feeling. It was a lot of emotions all in one. And I still go through the emotions every time I pull up to the store. It was life-changing.”

It All Worked Out

The fateful narrative deepens.

When Blunts and Moore dispensary was a cash-business target of robberies in 2020, Blunt was on a Zoom call with city council members and the Oakland Police Department, he said. That’s when he reconnected with Wingate, whom he hadn’t talked to since his arrest in 2005. The two became friends.

“When I went to try and buy a gun in 2020 and they’re like, ‘No, you can’t get one.’ I don’t know why. I’m going crazy,” said Blunt, who thought his convictions were reduced to misdemeanors, sealed and expunged years earlier.

That’s when Blunt went to Wingate for advice. His arresting officer from 15 years earlier said he had a connection at the county’s district attorney’s office and was willing to help Blunt navigate sealing his records, according to Blunt.

“I went and signed two pieces of paper, the DA found why those charges weren’t dismissed, she fixed all that, and now I’m no longer a felon,” Blunt said. “I can go own a firearm all thanks to the same officer who arrested me in ’05.”

Even beyond cannabis, the ripple effects of Blunt’s arrest are far-reaching.

When Blunt started his new job with Alameda County, he said he couldn’t work in the probation department while his arrest case was still open. So, he was transferred to another county office, where he ended up meeting his wife.

He said he would not have met his wife had he not been arrested.

“This is some whole, intertwined deep s--- that I’m a part of that I had no clue I was walking that path,” he said. “Even sitting here talking to you about it now, it’s still like pinchable, like I want to pinch myself, like, ‘This really happened?’ But that’s what really happened. I got snitched on and it worked out.”

Operating in Oakland

The string of robberies targeting all-cash cannabis businesses in Oakland continued into 2021, specifically with hundreds of roving caravans taking over the city the week of Nov. 15.

RELATED: Bay Area Cannabis Mayhem: 175 Shots Fired, Products Worth Millions Stolen

Blunt said the Oakland PD has since been more receptive and responsive to businesses affected by repeated criminal activity.

“They actually came to my store and took fingerprints, took evidence for the first time in four years,” he said. “So, that has helped. I haven’t heard anything about new robberies coming up. You know, I’m also into the streets and listening. But, so far, being that the criminals know that Oakland Police are no longer going to give them eight hours to roam around and target businesses, we have been a little less targeted.”

Stepping back further to take a broader temperature of the cannabis business climate in Oakland and in California, Blunt said his dispensary doors won’t be open in three years from now if the current tax rates and regulatory hurdles continue. He referred to California’s state-legal program as a rob-Peter-to-pay-Paul scenario under 2016’s voter-approved Proposition 64 and the subsequent Medical and Adult Use Cannabis Regulation and Safety Act (MAUCRSA).

While Gov. Gavin Newsom called for cannabis tax reform in his budget proposal last month, the state’s industry continues to be marred by a multilayered tax structure, security costs, regulatory burdens, falling prices, and overproduction from lack of open retail markets, which in turn have allowed the illicit market to continue to thrive.

“Business is great as far as being open, having a place in the community to enhance the community,” Blunt said. “We bring in money. But the overtaxation and the amount of money we spend on security is making it where there’s no profit at all. So, it’s lovely to do what I’m doing, but in California, it’s got about another three years and it’s going to be over with. And that’s not just me. That’s everybody.”

Lacking Representation

Blunt did say it’s an amazing feeling to be able to sell cannabis legally in his city, especially in regard to opening his doors 15 years after he was told “Blacks would never own” in the cannabis space.

But the reality is that while Black people make up 14% of the U.S. population, only about 2% of America’s estimated 30,000 cannabis companies are Black-owned, according to a 2021 Leafly report.

“Without the capital, without the education, without us as Black people realizing we can work together, if none of those things change, we’re going to continue to represent 2% in this space and the MSOs are going to continue to win,” Blunt said. “I do know a lot of us are working with the [diversity, equity and inclusion efforts] and trying to make sure it’s done right, but it’s not represented right at all. We’re the face of a space that we only have 2% ownership in. Like, that just doesn’t make any sense.”

With current barriers to entry, specifically capital, Blunt said his best piece of advice to other Black people who want to enter the space is to do so through ancillary business opportunities.

Considering taxation and regulatory burdens in California, Blunt said those who want to enter the industry through the plant-touching side of the business had better plan to make a $3-million to $5-million investment they won’t see a return on for at least three to five years.

“Everybody is blinded by growing and selling because they think everyone can be Cookies,” he said. “Everyone can’t be Cookies. Cookies is having hard time being Cookies. But they’re able to maneuver around because they have ancillary things they’re doing.

“You’ve got to just think smarter. But a lot of us are going for the green that we think is there and not really going for the green that’s real.”