Standing at 6 feet 9 inches tall, Al Harrington commands a room when he walks in it. But beyond his imposing stature is an affable personality and a deep-seated motivation to achieve social equity in the cannabis industry.

Best-known for his 16-year National Basketball Association career in which he scored more than 13,000 points in nearly 1,000 career games, Harrington transitioned to the cannabis industry when he launched Viola Extracts—now known as Viola Brands—in 2011 while playing for the Denver Nuggets.

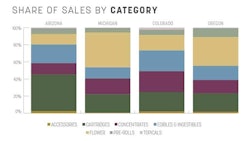

As co-founder and CEO of Viola, a multi-state operator with cultivation operations in Colorado, Michigan, and Oregon, Harrington built his company from the ground up over the past 11 years. Today, Viola has products available in six U.S. states—Michigan, California, Colorado, Oregon, Oklahoma, and Washington—and operates its own dispensary in Detroit. Viola products also became available in Canada in November 2021, and the company says it plans to launch in additional markets this year.

But even as Viola continues its rapid expansion across U.S. states and international lines, the company remains steadfast in its commitment to restoring the communities most impacted by the war on drugs.

“We’re really focused on building a high-quality, premium brand with purpose,” Harrington says. “And our purpose is all about using our platform to uplift, educate, empower, and be inclusive to people of color. We feel like we are directly tied to their success. … This is something we’re really focused on, and we’re never going to forget about our people.”

Early Days

The inspiration behind Viola Brands’ name is well-known—the company was named after Harrington’s grandmother, Viola, who suffered from glaucoma and found relief from cannabis.

“My grandmother was smoking the weed [and] she felt like her house was smelling like weed,” Harrington says. “So somebody told me about vapes and concentrates, and that’s how I learned about that. While learning that opportunity, I realized the only way to build a brand is to let people know you made [the product].”

Harrington says at the time Viola launched its first products in Colorado, flower was sold “deli style”, meaning there was no end-user packaging. “But with concentrates, there was,” Harrington says, “so we were able to really start a brand because we chose to go after concentrates initially.”

Harrington credits much of Viola’s success to his time spent as a fly on the wall in Denver’s cannabis scene during the company’s infancy.

“There was a spot in Denver called the HoodLab,” Harrington says. “In the back was an area where everybody would smoke, and it was almost like a think tank where everybody from the industry would just come in, hang out, and pretty much give secrets and just talk about what they dealt with that day and how they were able to fix the situation.”

That was where Harrington was first introduced to concentrates, which later became the foundation for Viola Extracts.

“These guys kept smoking this wax thing, and I’m like, what the hell are they smoking?,” Harrington says. “I tried it, I sat down, and I watched this dog sing for like three hours. He was singing the songs that were on the radio, I promise. That was my first experience with it.”

While the company later changed its name from Viola Extracts to Viola Brands as part of expanding its product portfolio to include flower and prerolls, Harrington is adamant that the company’s background in concentrates is what first put Viola on the map.

“I think the reason we have success today is because of that foundation,” Harrington says.

Giving Back

In an effort to achieve social equity, one of Viola’s specific goals is to create 100 black millionaires within the cannabis industry. A lofty task, by any measure, but one Harrington views as attainable through Viola Cares, the company’s social equity initiative launched in February 2020. Viola Cares focuses on community engagement, working with local and national organizations to provide expungement, social justice reform, and more, with the goal of creating more than 10,000 jobs and expanding diversity in the cannabis industry.

“We are a company that is owned by a [black] person,” Harrington says. “For us, it’s bigger than just product. It’s about our overall impact and overall presence being in an industry that is pretty much trying to keep us out of it. I feel like social equity is a ‘check-the-box’ issue for a lot of governments and MSOs [when] it should be a priority to make sure we’re involved.”

As part of this initiative, Viola partnered with Ball Family Farms, one of the first black social equity licensees in Los Angeles, to launch its Purple Reign cultivar during the height of the George Floyd and racial justice protests in 2020. (Editor’s Note: See CBT’s October 2021 issue featuring Ball Family Farms at bit.ly/CBT-BFF.) Both companies pledged $1 from each Purple Reign sale to Root & Rebound, an organization that provides education, legal advocacy, and policy reform on behalf of families and communities most impacted by mass incarceration.

In October 2020, Viola launched its incubator program to provide operational support to black entrepreneurs in the cannabis industry. The initial strategic partner for the program was Gold Standard Farms, a black family-owned hemp farm with history in traditional agriculture dating back more than 80 years, according to the company’s CEO Jarrel Howard.

Howard admits while he was hesitant to enter the hemp cultivation space, he was inspired by Harrington’s leadership, guidance, and belief in Gold Standard Farms.

“Al really took his time with us in wanting us to do it right,” Howard says. “We sat with him and his [team], and they gave us a blueprint of what to look out for, things to do when building facilities, different climate controls, HVAC systems, the full works. Al allowed me to follow him every month, meet him in LA or wherever he was just to see how the day-to-day works, things that he goes through as a CEO of a multi-state operator, and things to expect because policies are changing daily. So that was a blessing.”

The newest partner in Viola’s incubator is Mezz Brands, a Colorado-based vape and pre-roll brand that joined the program in June 2021.

Erin Hackney, founding partner and CEO of Mezz Brands, says Harrington has served as a mentor to him in the cannabis industry since the two first met in 2017. Hackney says Mezz’s involvement in Viola’s incubator program allows his company to benefit from Viola’s infrastructure, including operational support with finance, marketing, public relations, and more.

“That was the biggest part for Mezz; we built the brand, we have the success, but we also needed to scale outside of the markets we were in,” Hackney says. “Viola brings the scalability outside of our current markets. Having Al sit next to you during an investor pitch, it means a lot that Al is going to say, ‘I’m all in with building this young, minority[-owned] company.’”

While Viola assists Mezz Brands with cannabis standard operating procedures (SOPs), Harrington sought Hackney’s business expertise, stemming from his background in corporate business development, when Viola wanted to expand its infrastructure in 2019.

“I started helping him with how to structure an organization, identifying talent for Viola, and it just grew into this relationship,” Hackney explains. (He also has served as Viola’s chief of staff since 2019.) “I’ve been behind the scenes as Al’s shadow as he builds Viola.”

Regarding Viola’s incubator program, Harrington emphasizes the importance of education and operational support as opposed to simply writing blank checks and rushing companies to market before they’re ready.

“We feel like once we build this thing out, not only can we supply capital, [but] we can also give our SOPs and information and be a crutch for these companies,” Harrington says. “At the end of the day, I want them to be successful. I don’t want to take their businesses. We want them to be able to have an impact within the industry so they can have an impact in their community.”

RELATED: Viola Closes $13-Million Bridge Round

Hackney explains that Viola’s goal is to include those incubator companies in Viola’s portfolio of brands as the company expands its footprint.

“Now it’s not just a conversation about one brand being on the shelf, Al can have a conversation about having the entire shelf and then stocking with the brands that he supports,” Hackney says. “Al’s giving minority organizations the opportunity to come up under this massive umbrella that he’s built and go along for the ride.”

In order to sustain that “massive umbrella” Viola provides for its incubator companies and social equity programs, Harrington acknowledges Viola must meet certain financial goals, but he’s currently building a network of professionals to join Viola in its push for social equity.

“I’ve been able to tap into some of our other resources—starting in 2022, and I can’t talk about it yet—where we will make it more sustainable, where I have other people supporting the cause, and trying to figure out how to dedicate percentages of sales or different things like that to this initiative,” he says. “As a group and as an industry, and especially for the black companies, we all realize that the main issue around all of this is the lack of education.”

Emphasis on Education

One of the main reasons Harrington is so adamant about the need for cannabis education is he feels the industry is only scratching the surface of its potential.

“A lot of the talent in cannabis hasn’t entered [the industry] yet,” Harrington says. “Until people of color really are able to start putting their imprint on this industry, I just feel like [the industry’s potential is] just not being met.”

In September 2021, Viola launched the Harrington Institute of Cannabis Education in partnership with the Cleveland School of Cannabis to provide education programs for entrepreneurs in the cannabis industry. The Harrington Institute offers partial and full class scholarships for students of color affected by the war on drugs.

“What we try to focus on in this first round of courses is a baseline level of information in different categories within this space,” Harrington says. “People from the outside think the only opportunity [in the cannabis industry] is to grow weed and sell it. And a lot of people were afraid of that, not realizing that there’s testing, there’s packaging, there’s media, there’s security, there’s all these other things. We’re going to need accountants, we’re going to need all kinds of different professionals. So how do you initially get your feet wet and get into the industry? You need to have that baseline education to be able to make those right decisions.”

Since its inception in 2017, the Cleveland School of Cannabis has nearly 700 graduates with a job placement rate of 65%, according to the school.

Culture Collaboration

Another notable recent launch for Viola is its Iverson ’96 cultivar, which debuted October 2021, in partnership with NBA legend Allen Iverson. The Iverson ’96 cultivar is Viola’s first national rollout collaboration, with Harrington wanting it “to be with somebody iconic.”

“You don’t say this when you compete against him, but we all looked up to [Iverson] even though we were playing against him,” Harrington says. “He was representing us at the highest level. He allowed us to come out of our shells and be who we were. … So when I thought about the fact he was a pioneering trailblazer, it correlated to what I’m doing with Viola as a real pioneer in the cannabis space. So why not partner with somebody that has done that before, [that] people can recognize? I just thought it was a natural fit for us.”

Viola also welcomes the idea of collaborating with other cannabis companies, noting that it’s too early in the industry to view other companies as strictly competitors.

“When you think about these large MSOs, they are competitors and partners at the same time,” Hackney says. “Think about Cookies, for example. Cookies and Viola are often compared to one another, but Al and the owners of Cookies are good friends and they do business together. A Viola product could go into a Cookies store, [and] a Cookies product could go into a Viola store, so the consumer should win at the end of the day.”

Cultivation Specifics

Viola has cultivation facilities in Colorado, Michigan, and Oregon, comprising 122,000 square feet of grow space.

Viola currently uses HPS lights across all three facilities, although Harrington acknowledges the industry’s, and Viola’s, shift toward LED lighting.

“We’re starting to put some R&D rooms in our facilities to start introducing [LED lighting] and learning that process and trying to dial in that process so we can eventually get there because it’s just more cost-effective and it makes sense,” Harrington says.

Viola also cultivates using a coco base and a proprietary nutrient mix from its growers, according to Harrington. When it comes to irrigation, Harrington says the company implements both hand-watering and irrigation systems, varying depending on which Viola facility you’re at.

“We hand-water in Colorado, but we have water irrigation in Michigan,” Harrington says. “I visit facilities all the time, and [people are] still on the fence of irrigation or hand-water. Some [growers] feel like they need that personal touch and personal relationship with the plant in order to get super high-quality results. So we’re still figuring that out as well.”

One post-harvest process that Viola isn’t ambivalent about, however, is hand-trimming the buds. Harrington says Viola tried automating its trimming processes in the past, but ultimately felt that too much resin, as well as each bud’s unique structure, was being lost in the process.

Harrington notes the difference between growing for concentrate and growing for flower, saying Viola had to learn the latter as the company expanded its product portfolio.

“There is some nuance to that, especially when you’re growing at scale,” he says. “Making sure you have the proper size trim, drying rooms, temperatures, and different things like that—I think that stuff is always being dialed in.”

Growing Pains

As the cannabis industry continues to evolve, Harrington notes there are a number of changes he’d like to see throughout the industry.

“The first thing I would do is change the tax law, 280E,” Harrington says. “It’s really just such a hindrance where it just doesn’t allow you to run a business, essentially. It keeps you behind the eight ball. It’s just fucked up.”

Another challenge unique to the cannabis industry is how legacy operators and new-school money can co-exist, if not work in tandem.

“We’re going to have to work together,” Harrington says. “From a legacy standpoint, if you don’t figure out how to work out, you might get left out because we’ve all seen historically [that] money trumps everything.”

With that said, the grower is “the most important guy in the room,” Harrington says, “because if you have shitty weed, you don’t sell anything.”

Harrington mentions legacy operators often want to feel appreciated for their contributions to the industry rather than just being taken advantage of by cannabis conglomerates. And as corporations continue to invest and stake their claim in the cannabis industry, Harrington also believes local governments have an obligation to put action and funding, rather than just words, behind social equity efforts.

“This tax money from cannabis is an add-on, it’s a new industry,” Harrington says. “So why can’t you take 20% of revenue and dedicate it towards the social equity programs in the state to help build these people up?”

Looking Forward

Despite potential headwinds, Harrington remains optimistic in his long-term outlook for the U.S. cannabis industry.

“I think [cannabis] will probably be de-scheduled in the next five years, for sure, if not fully federally legal,” he says. “I think banking will open up, which obviously will see the industry change a lot. We’re going to see Coca-Cola, we’re going to see all these big conglomerates staking their claim in the industry because for them it makes a lot of sense in regards to what they’ve already been doing.”

Harrington believes brands will ultimately rule the day in the U.S. cannabis industry, even over specific cultivators and/or retailers.

“You can take a brand and you can scale it, you can move it all around the world,” he says. “All you have to do is lock in supply, and that’s what Viola is really focused on.”

But even as industry headlines focus on federal legalization efforts, new state markets coming online, and further industry investment, Viola remains unwavering in its push for social equity.

“We mean everything to [social equity],” Harrington says. “That’s who we represent and, from a non-monetary standpoint, the first thing that Viola has to do is to continue to talk about the disparities and the lack of diversity and keep that at the forefront. Just because we’re successful or we’re winning licenses doesn’t mean the overall goal is being met, [which is] for multiple people of color to participate in this space.”