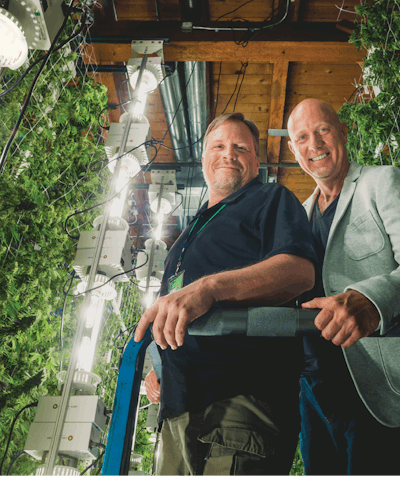

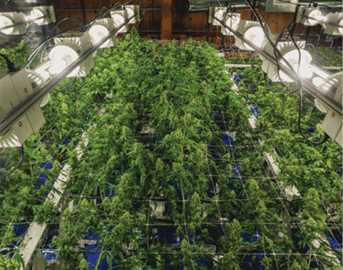

The grow space at Colorado’s Best Inc. in Denver covers 13,000 square feet, though that’s not counting the 16-foot-tall racks the cultivation company uses to grow on multiple levels.

The system Colorado’s Best uses was one that the owners – Tony Frischknecht and Joseph Carcusa – helped develop in 2013 as a prototype for a vertical harvest design that they would use to maximize their space while growing full-size plants. The prototype was designed by amateur inventor Adam Hudgins, grow manager for Colorado’s Best, whose commercial cultivation background had him always on the hunt for ways to grow more efficiently.

That prototype became what is called the Ideal Harvest system, with Hudgins staying on as lead consultant for the system’s design and installation.

Cannabis Business Times’ Managing Editor Kyle Brown talked with Hudgins and Frischknecht about the vertical grow system design and how it gave Colorado’s Best a new perspective on staying ahead of the competition.

Kyle Brown: Tell me about the benefits of the vertical grow.

Adam Hudgins: First, you want to look at square footage. What … am I paying for? Traditionally, [grows] take place in big warehouses [with] tall ceilings. Maximizing the square footage is the main thing. By going up, it allows us to utilize that expensive air we’ve been paying for. This gave us the ability to double our total capacity on one side of our building and still shut down two rooms, just to give you an idea of the dramatic change. That’s really the crux of vertical — the use of the volume of the room and not just the square footage.

We manage a room that has 532 plants in it with one person. There’s a huge reduction in labor and … in overall cost. It’s basically one big mechanical advantage that creates a really high efficiency rig … designed to maximize space and inputs via power, people, nutrients, water. We control all those things more tightly than we ever have, with the vertical grow system.

We had a big increase in yield, but it doubled our actual plant count without us buying one more square inch of real estate. That’s huge.”

Brown: What does the day-to-day look like?

Hudgins: Day-to-day is really interesting. When you’re not in the room, the shelves are at what we call the growing distance. You’ve got this nice, close proximity of light to plant. We’ve got two rooms that flip at noon. The first vertical room we work from 6:30 [a.m.] to noon — we have one tech that’s married to that room. He’s going to care for 532 plants, just him.

You drive into the aisle with a scissor lift. We want to try to take as much human power out, and create a more efficient solution. The ergonomics of it are huge; that’s what really helps reduce the labor cost. We just travel across the racks on the lift. You work in blocks; that way you cover every plant, and everything’s going to get inspected. The [aisles] open up to five feet or more allowing the tech to access all the plants. Although the tech can check on his entire crop from the ground, he will inspect the majority of the plants from the lift, giving him the ability to get up close and personal.

The whole system runs on automated water and feed. Even though it’s automated, the watering [takes] place while [the tech is] there, so he can watch it and make sure everything’s happy. If he needs to spray, he’ll spray. If he needs to prune, he’ll prune. That room goes dark at noon, he moves the lift out, closes the aisles back to the growing distance. Then we move to the second room, which is noon to 3:30, and it’s [managed] by one tech also. That’s all going to happen every day.

Tony Frischknecht: It used to take several people in this room, [which] held half the plants [we have now], so probably three people to manage 120 plants. Now we’re down to one, so labor costs are a third of what they used to be.

Brown: What about this system makes it so that one person can do so much?

Hudgins: The automated water and feed is huge. [But] what really makes it manageable by one person is that the way the spaces are set, you’re able to come in and drive along with the lift. It’s a more sensible approach and lays out very logically. … There are not any deep grow tables you have to stretch over or work around. I mean, it is high-density, but it’s the nature of the layout that allows it to be worked on by one person.

Brown: How did implementing a vertical grow change your operation?

Hudgins: The biggest change is that it doubled our capacity. We had a big increase in yield, but it doubled our actual plant count without us buying one more square inch of real estate. That’s huge.

Frischknecht: A lot of the commercial real estate in Denver is three and four times the cost of any normal business, so that’s tough to [offset]. How much more do we have to grow to make this indoor grow a viable option and make our costs go down as a business owner? We have to stay competitive. Especially in a dense area like Denver, there’s not a whole lot of space left, and what’s left comes at a premium.

Hudgins: The nature of the rig is so modular, the potholders themselves can be moved. We’ve grown giant sativas right next to small, squatty indicas. [It] actually allows for way more flexibility when it comes to strains. … That’s one of the things that we do that’s different from a lot of other vertical options growers use. Most other verticals are horizontal tray-based; we produce a full-size plant.

Brown: Tell me about the intricacies of the system.

Hudgins: The racks are steel. Fully loaded, you can have this giant rack of plants, and you can move it with one touch of the finger. This moves the entire setup back and forth, in that operating and growing distance.

The water tanks … reside in the room next door. You have all your nutrients right there with your tanks. For the water system, the emitters are positioned behind the plants, and we also have multiple zones. So if you have a warmer microclimate at the top of the rack, we’re able to tune that zone for more or less water.

Of course, the lights run on timers. For the HVAC, we can [control] temperature and humidity, pretty common stuff. … But, at that point, we have chosen to back off on some technology, because we want a certain amount of hands-on.

Brown: How does lighting work in that setup?

Hudgins: We’ve been [fitting] all of our new ones with the 315-watt ceramic discharge lamp. We partnered with a company called Boulder Lamp … and they converted their 315 watt for vertical. The ballast is mounted on the light rail, and we [stack them beside the grow]. Our preference is the 315, because it produces a broader spectrum. You’re going to get a healthier plant that way, and we’re also able to cover more ground because the light itself uses less power. It’s low amp, lower heat, and basically we’ve been able to replace 1,000-watts [high-pressure sodium bulbs] with two 315-watt ceramic bulbs.

Between two [sets of racks], you have what we call stacks [of lights]. We have currently in our facility 10 315s per stack. Those are aligned vertically up a rail. The lights run vertically on a movable bar that basically protrudes in front of the plants. It’s adjustable, so we may start off a little closer and then end up at roughly 18 inches away when it gets closer to harvest time. We’re very, very close to the plant, though. That’s where [a lot of] the benefit of the vertical grow comes from, from the plants using 360 degrees of the light bulb. It’s a little more natural.

Brown: How does this affect your work with clones?

Hudgins: We do really big business in clones, actually. Vertical … doubled our capacity. [So] we have to draw more from our clone bank … to feed our warehouse. That was a part of our planning process. We knew [if] we were going to need more veg, we were going to need more clones. That means we need more mother space. Planning for these kinds of projects is key.

Brown: What challenges have you faced in making the change?

Hudgins: As with anything, cost is going to be first. For us, it was a retrofit. We had to figure out how to move power from our old rooms, and move AC from our old rooms. The biggest challenge for us is cost, but also for a production facility like this, it’s timing. We can’t afford to shut these rigs down and have them sit empty for three months let alone one week.

Frischknecht: It’s a custom job, right? So we had to … work with electricians to move all power to these new rooms. We had to get bids on all new AC installs. The air-condition and climate control is probably the most challenging to get dialed in at any grow. It takes a lot of time and even more money.

As an owner, you can’t afford to have [the cultivation] down. It could put us out of business if we didn’t time everything just right.

Brown: How did you sell your investors on this?

Frischknecht: [As for the investors], which were the owners of Colorado’s Best, … the big selling point for us was [that] Colorado is a very sunny state. For 320 days of the year, we get sunlight. So we knew our next competitors were going to be doing a lot of outdoor, a lot of greenhouse. We didn’t have the luxury of moving our operation outside. We had to figure out how to compete, because the price per pound is dropping all the time.

It was a risk for us, because we had to invest some money. But when we saw … that we could grow our plant canopy about four times as much as what we had in one room and chop our labor down, that’s what really sold us. … When we outfitted our building, we saw about a 40 percent reduction in our costs overall.

Brown: If you’re talking to someone considering this, what do you need to get right at the outset?

Hudgins: … You need to have a plan and stick to the plan. Time is not on your side in these kinds of endeavors. … Six months of sitting empty will absolutely break your bank. If you open a big building, and you spend everything you have on it, you really need to get that return back as fast as possible.

Frischknecht: The challenge in planning is the knowledge of the grower and who you’re working with. How knowledgeable are they? Because it doesn’t work if you don’t work as a team on the project.