On Jan. 29, Santa Barbara County supervisors organized what turned out to be a contentious meeting on cannabis regulations. About a year prior, the county passed its local cannabis ordinance, and it was time to check in and evaluate the progress thus far; the public, as noted in a December New York Times article on the county’s cannabis cultivation odor issues, was not overwhelmingly supportive. Audience members at the meeting wore clothespins attached to lapels and collars, signifying “the need to pinch their noses,” as a reporter from the local ABC news affiliate, KEYT-TV, explained.

“We’ve had enough,” Carpinteria resident Maureen Foley Claffey said at the meeting, according to a report by the local news outlet Coastal View. “Pot stinks, and we’re mad as hell.”

As municipalities and county governments around the U.S. are finding out, regulating a new industry forces a steep learning curve.

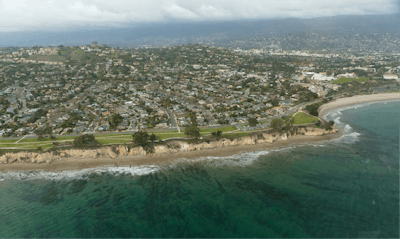

Das Williams, supervisor for the First District of Santa Barbara County, has been at the forefront of cannabis regulation development so that the county would have something on the books and a legal foundation. In addition to organizing public hearings in Santa Maria, Williams even hosted a community meeting at his home in Carpinteria, the coastal city of 13,600 residents all neatly packed in among 14 square blocks. In those meetings, he learned that odor is a top concern for community members.

“Getting odor control right is just crucial for any community where there is close proximity between growers and a large number of residents,” Williams says.

Santa Barbara County started by building odor control technology requirements into the county’s zoning codes. “We put a term that is used in laws often of ‘best available technology’ that preserves our ability as technology improves to ask for better odor control—and demand better odor control,” Williams says.

In addition to licensing requirements, counties can control land use requirements as part of their odor control tools, meaning they can determine what type of structure or business can occupy which zones.

“If you mandate odor control, you are de facto banning outdoor cultivation in a zone where you mandate odor control,” Williams says. “And so, we have done that in Carpinteria. We have both de facto banned outdoor cultivation … by mandating odor control, and we’ve done it de jure by requiring a buffer of 1,500 square feet between residences and outdoor operations. In Carpinteria, that means there’s only two or three parcels that would qualify. … Essentially, our permitting tends to favor greenhouses.”

Carpinteria’s population density is just over 1,400 people per square mile, according to 2010 U.S. Census figures, more than five times California’s average of 251 people per square mile. Williams says his county’s plan worked for his densely populated corner of the California cannabis market. In communities with different population densities, however, Williams counsels a more personalized approach.

Complaints and Solutions

The onus is on greenhouse operations to apply the “best available technology” to keep their plants’ odor at a reasonable standard. Dennis Bozanich, deputy county executive officer with Santa Barbara County, says that the legislation has given his agency a proper baseline for enforcing local code. It’s a work in progress, as most cannabis laws are, but it’s given him and his team a path forward to work with both businesses and residents.

“It does tend to be complaint-driven, but it’s also proactive as well,” Bozanich says. “As part of the compliance team, we have staff regularly visiting licensed operators, identifying practices or business operations that are outside of the requirements established in our local regulations. We then cite and/or come up with an improvement plan for them to come back into compliance.”

Further, the ability to enforce an ordinance gives Bozanich a chance to suss out illicit grow operations in the county. When responding to a complaint, the county team will first assess whether it can be traced to a nearby licensed grow facility; other times, a complaint may lead them to an unlicensed business that needs to be shut down. The county spends $1.7 million per year on an enforcement team that’s eradicated about 1 million plants from July 2018 to March 2019, Bozanich says.

Often enough, though, he says the county is building cannabis odor into a more proactive conversation with licensed growers.

“At times,” Bozanich says, “we will go to an operator as part of our compliance check to say, ‘Look, we’re continuing to get a large number of other complaints. When was the last time you looked at your own odor control system? Is everything operating normally? Are there any service needs? Were there any purposes for which you had the system shut down for any period of time, for routine maintenance, for example? What was the duration of that?’ And then we’re working with them to make sure they are operating that odor control system as consistently and as finely tuned as possible.”

When it comes to selecting an odor control technology, Williams says “the real key here is: What’s the maximal effectiveness of a system that you can do with the lowest energy use?

“That’s a balance. If the energy use is so high, then the operator will be tempted to turn it off sometimes. … That of course would defeat the purpose. So, getting this right from a technical perspective and from a standards and community expectations perspective is really important,” he says.

And it is, in the end, a conversation. As the licensed cannabis industry comes into its own, Santa Barbara is joining an increasing number of local governments and business communities trying to wrangle an understanding of how cannabis will interface with the rest of society.

Williams and his fellow supervisors talked to professionals in solid waste circles and in the odor control vendor community. Then, of course, the growers and Santa Barbara residents weighed in on how to enforce this balancing act.

“We’re still learning,” Williams says. “I don’t want to say that we’ve gotten it all down. We established in the ordinance a standard, and we will, by experience, learn how to do it better.”