Photos by Peter Garritano except where noted

Last November, just before Thanksgiving, Mark Justh and Dan Dolgin decided to spread liquid dairy manure across the hemp stalks left behind from their fall harvest. The co-owners of Eaton Hemp and JD Farms in upstate New York saw this as an opportunity to bridge one season to the next and, as an organic farm certified by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), the work kept them close to their roots. Even when it would appear as though their work with hemp was done for the year, the crop just doesn’t stop giving back.

This green manure plow down is part and parcel of the team’s overall ethos. From the farm’s earliest days, even before hemp began disrupting the agriculture marketplace, Justh saw JD Farms as an opportunity to go all-in on an organic business practice and lifestyle.

Eaton Hemp, the organic hemp food brand born out of JD Farms’ foray into the U.S.’s newest agricultural market, was the first licensed business to plant the crop in New York state in 80 years. That was in 2016. Now, only four years after its first seeds went into the farm’s fertile ground, Eaton Hemp sits on the vanguard of the hemp industry’s organic grain market while actively conducting small-scale research and development in the cannabidiol (CBD) space. Business partners Justh and Dolgin have kept busy. This is a necessary part of the lifestyle in the quickly evolving hemp industry.

“It’s been a long and winding road through the industry, and there’s ups and downs,” Dolgin says, “and I think you just have to learn to ride them out and find a workaround.”

The company now markets its Eaton Hemp Super Squares—neat little raw bars that come in dark chocolate sea salt, cashew coconut mango and walnut apple cinnamon flavors—and Eaton Hemp Toasted Super Seeds, which come in Himalayan pink salt, ancho BBQ and maple cinnamon flavors, all following trends gleaned from organic food distributors. Eaton Hemp’s product lines, launched in April 2018, are sold online and in more than 200 retail markets in the New York tri-state area.

“What we found out when we brought our product to market is that people know hemp, but they know it more as CBD now,” Dolgin says. “They don’t know it as food as much, so they give you a quizzical look when you say you [make] hemp food or you have snacks. Then, when they taste it, it’s really quite amazing to watch. Their eyes light up and they’re like, ‘Wow, this is delicious,’ and then they understand all the nutritional benefits.” With high omega-3 and -6 fatty acids, the seed is a powerful source of protein that has been reported to alleviate inflammation and boost immune health, making it an easy choice for today’s dietary, environmentally and health-conscious food consumers.

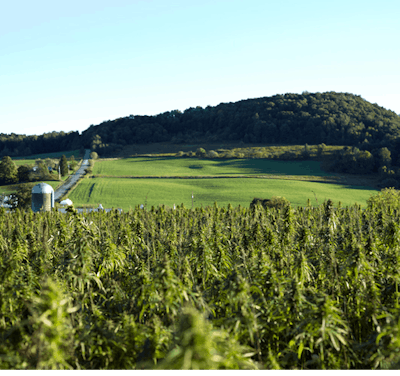

Eaton Hemp comes from JD Farms’ 2,000-plus acres of farmland as well as other organic farms they contract with throughout the U.S. to diversify the business’s growing climates and account for weather volatility. But the story behind Eaton Hemp comes from the gently rolling foothills of upstate New York, where Justh happened upon an old dairy property in 2008. By the time Dolgin joined the business in 2015, the state was gathering its regulatory senses for an industrial hemp research pilot program. From there, JD Farms took off running and hasn’t stopped since.

* * *

They’d been warned about the plant’s tenacious coil, but Justh says, “What we realized is that ... it was almost like the hemp would weave a tapestry around all of the moving parts of your combine.”

While the hemp industry is itself part of a vast, global agricultural ecosystem, so too is JD Farms part of something larger than itself. The whole idea was that Justh wanted to return, in a way, to the rural landscape of his youth. After a career in international finance, which he started in the mid-1990s, the quieter side of life in the U.S. economy appealed to him. As his three children were growing up and he was working across the globe, he found the idea of getting back to his roots hard to resist.

A growing awareness of sustainable agricultural practices was a prime mover for Justh, who credits things like Wendell Berry’s back-to-the-land poetry and Michael Pollan’s The Omnivore’s Dilemma with his decision to move into the farming world. By then, though, his central Pennsylvania hometown region had succumbed to suburban sprawl, and so Justh took to the internet and started scouting farmland north of New York City.

After long days at JPMorgan, he’d unwind by scrolling through available acreage on landandfarm.com. In the Hudson Valley, he found himself competing with families who were looking for second homes. Justh was in the market for pure farmland, and he moved his sight lines deeper into the state to Madison County, which sits between Syracuse and rural Cooperstown, best known as the site of the Baseball Hall of Fame.

In the small town of Eaton, Justh found the remnants of a regional dairy industry on the brink of extinction. He landed a 1,500-acre farm that seemed almost too good to be true.

“When I saw this one, what I saw here was that there were a number of streams and small rivers and creeks that went through it,” Justh says. “It had agricultural infrastructure, but it was left fallow because the prior owner had sadly basically gone bankrupt.”

At that point, hemp wasn’t on Justh’s radar. His ambitions were focused on the bucolic work of practicing sustainable farming. He set out into the organic hay business with the intention of selling 1,000-acre harvests as feed for central New York’s rebounding organic milk market. “I thought, ‘Well, I will be able to convert this to organic over time,’” he says, “and that was the initial vision of the farm.”

Early on, he used sorghum-sudangrass as an effective cover crop in his rotation. He was learning the trade and feeling out what was going to work best on his farm. But he wanted a firmer, high-canopy crop that could also do some damage to encroaching weeds. It helped that hemp could pull double duty as animal bedding and feed for JD Farms’ pasture pigs and cows. The idea proved irresistible.

“The original impetus for hemp was, ‘OK, what can I use as a weed suppressant that’s going to grow very quickly and I can harvest and it might have a myriad of uses?’” Justh says. “Well, it had all those things—except it was illegal. And thus enters Dan into my world.”

* * *

Before converging with Justh at the farm in Eaton, Dolgin had worked for years in national security. He worked for the Director of National Intelligence and then the National Counterterrorism Center in Washington, D.C. Around 2010, he left government and took up work in private sector consulting in New York City. He was asked to be the chief security officer for a company that was trying to win one of the initial medial cannabis licenses in New York back in early 2015. That company didn’t win a license, which, for Dolgin, may have been just the ticket he needed to spin unexpectedly toward the nascent hemp industry.

In his networking among the medical cannabis set in New York, Dolgin met Justh, who was still mulling hemp as a cover crop up in Eaton. The idea of getting into the hemp space was intriguing, especially because Dolgin was familiar by then with the state government systems that could legalize a pilot program under Congress’ Agricultural Act of 2014 (the 2014 Farm Bill) requirements.

Dolgin thought, “Well, life is what you make when you’ve got these various crossroads—when you can’t really see the forest for the trees—but you certainly know it’s going to be an exciting journey.” The two agreed to partner and dive into the hemp industry together. Justh’s agricultural ambitions blended neatly with Dolgin’s political savvy.

Simply to get the HGI seeds in the ground, the guys at JD Farms were directed by the DEA to have a uniformed armed guard accompany them.

The 2014 Farm Bill mandated a partnership with a research institution. The State University of New York (SUNY) at Morrisville, located just up the road from Eaton, was on board. Jennifer Gilbert Jenkins, Ph.D., assistant professor of agricultural science at the school, became the point person for JD Farms’ work with the support of the university’s dean and president.

“Dan and Mark came to SUNY Morrisville and said, ‘We’re working with the legislature on a bill to legalize industrial hemp production, and we think that the bill is going to require there to be research partners with academic institutions,’” she says, referring to their efforts to establish a state program under the 2014 Farm Bill. “‘Would SUNY Morrisville be interested?’ And we said, ‘Heck yeah, that sounds like fun.’” She’d only been at the school for two months, and hemp research quickly became her focal point.

Because there wasn’t really an agricultural foundation for hemp in the U.S., a lot of the early work under JD Farms’ license involved planting seeds and observing what happens. This was research starting from square one. The SUNY Morrisville team took close notes on things like weed emergence, germination rates, insect populations, moisture content and so on. Canadian research provided guidance, as our northern neighbor legalized hemp cultivation in 1998, but much of the scientific record leaned on hemp’s similarity to wheat as a row crop. “I didn’t want to treat hemp like wheat,” Jenkins says. “I wanted to treat hemp like hemp.”

Because hemp was only legal in that narrow context of the 2014 Farm Bill, growers like Justh and Dolgin needed to acquire a permit from the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) to import hemp seed. With no domestic source at that time, growers looked to Canada and Europe to begin operations. Justh and Dolgin linked up with Hemp Genetics International (HGI) in western Canada for their supply. Simply to get the HGI seeds in the ground, the guys at JD Farms were directed by the DEA to have a uniformed armed guard accompany them.

When the seeds went into the fertile soil of Madison County in the spring of 2016, it was the first time in 80 years that anyone had planted legal hemp in New York state. Justh and Dolgin had before them a 30-acre bumper crop that would jump-start the state’s newest industry.

The original iteration of New York’s bill, however, required hemp growers to burn their crop at the end of the season. The intention was based entirely in plant research with no allowance for any commercial sales. Justh and Dolgin, now acquainted somewhat with the early stirrings of the domestic industry, helped draft a new state bill that would allow a commercial outlet for hemp farms licensed for research purposes. In August 2016, Gov. Andrew Cuomo signed the legislation into law, giving JD Farms enough time to plan ahead for a real harvest that fall. Swift action, as it turns out, has proven vital in this industry.

“What we’ve found in terms of farming in general is that farms can survive small mistakes,” Dolgin says, “but big ones are a lot tougher.”

* * *

That first year, with those 30 acres planted at the Eaton farm, was a good one. But the lessons learned came with their fair share of challenges.

What the team quickly began to learn is that Cannabis sativa L. is a very different plant than sorghum-sudangrass or anything along those lines. There were the little things: hemp stalks wrapping around power take-off drives and axles. They’d been warned about the plant’s tenacious coil, but this seemed like no big deal to farmers who’d been cutting hay for the past few years.

“What we realized is that, truly, it was almost like the hemp would weave a tapestry around all of the moving parts of your combine,” Justh says. “It was pretty terrifying to pull out literally woven blankets of hemp from your combine.”

It was a learning curve, and Justh and Dolgin both worked closely with Jenkins and her team to more intimately understand this unique plant.

“When they talk about hemp being somewhat difficult to harvest, you really have to treat it with respect and dignity,” he says. “That’s because if you don’t, you’ll—unless you have a very good insurance policy—have burning combines and things like that. So, you want to really take it slow and be thoughtful when you’re harvesting it, and really understand that it is a special crop on harvest—hence why they make rope and textiles out of it.”

And then there were the larger issues, like figuring out what to do with this crop. They brought former ad executive Bryan D’Alessandro onto the team as CEO the following year, in 2017, to shepherd the work of JD Farms into what would become Eaton Hemp. With a background in marketing strategy and branding, D’Alessandro brought a skill set that would complement the agricultural learning curve Justh and Dolgin were riding.

They had a license, and so they knew they had a valuable asset that they could shop around among prospective acquirers or buying partners. But they soon came to believe their own lifestyles could guide their plans; D’Alessandro showed them the pathway toward developing their own brand within the evolving natural food space. Justh, an ultrarunner who boxes Muay Thai, saw this opportunity as a true-to-form outgrowth of what he’d been doing for the past several years.

“It’s funny, because it was really hard to see beyond the next hurdle at that point,” Dolgin says. “It was really, really hard to consider the larger picture.” Now, in 2020, when he talks about the rapidly developing legal hemp industry, he makes a point of telling farmers they’ll need to line up buyers before putting seeds in the ground. But back then?

That’s the story of hemp in early 2020: learning how to set expectations in line with supply and demand curves that haven’t yet settled into predictable patterns.

“We brought [D’Alessandro] in to help us really formulate a plan and launch the brand, which is now Eaton Hemp,” Dolgin says, “but it took two, three years of both growing on the farm and also exploring the space, figuring out what products we wanted to make, finding co-packers, distributors, so on and so forth.”

As recently as 2016, finding capable co-packers in the hemp space was a near impossibility. Lining up business partnerships was a shot in the dark for anyone able to work with a research license in the early days.

“I think because we had a diverse portfolio, we could take the risk in that initial year,” Dolgin says. “[We said to ourselves] well, let’s see how this grows and let’s kind of follow along and see what the market naturally leads us to. We explored a number of different opportunities and thoughts—and the fiber aspect and the seed and everything in between.”

With that first harvest, the team could begin tasting the actual seeds. Could the natural food industry be some sort of commercial outlet here? CBD wasn’t as popular on the market like it is today; the guys at JD Farms were looking squarely through a sustainable agricultural lens and trying to think one or two steps ahead of where they were.

* * *

For all the bright spots the trio saw in 2016, the next year flipped the script. All told, that second hemp crop was a wash. “Had we started in 2017, I don’t know if we would [still] participate in the industry,” Dolgin says, “because everything that was good about ’16, at least agriculturally speaking, was bad about ’17.”

The spring saw a cold, wet start to the planting season, and the team at JD Farms planted earlier than they did their first year. They also quadrupled their bets and planted about 150 acres.

“We reduced the density and we planted … not as deep into the soil and really got wiped out,” Dolgin says. “I mean, it rained. It was one of these years where you’re just sitting inside, looking outside and shaking your fist at the sky, but there’s really nothing you can do.”

The team saved the season by doubling down on goldenrod crops for essential oils. Still, they swathed and windrowed the hemp crop, which allowed them to save what was left after the weeds died down.

As organic farmers diving into the hemp business, Justh and Dolgin learned they couldn’t plant their hemp crops on the same land they used the previous season. Hemp is a nitrogen-depleting crop, and they found the soil was in need of nutrients the following year. Now, the Eaton team plants nitrogen-giving clover crops between seasons. It was important to knock out a few of those big lessons early on.

“For us, it was definitely: don’t plant it in the same fields twice, don’t plant it quite as early, don’t plant it as shallow as we did, then also hope it doesn’t rain as much as it did,” Justh says. “So, those were our lessons as we went into 2018.”

By that point, SUNY Morrisville had begun growing hemp crops on its own campus farm, and Cornell University had joined JD Farms as a research partner. Jenkins’ former student, Chris Domanski, even went on to join JD Farms as greenhouse manager at the company’s newly built 5,000-square-foot climate-controlled facility.

But all of those lessons and progress are for naught without a commercial plan in this industry. Especially since the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 (the 2018 Farm Bill) passed, the hemp market has become a bustling and nuanced place, where it takes a keen eye for opportunity and a healthy risk tolerance to succeed.

“No one is going to knock on your door just because you put hemp in the ground and pay you good money for it,” Dolgin says. “You [may] have 30,000 different uses for hemp, but there’s not 30,000 markets, for sure. And even the markets that do exist, you really have to either have a buyer in place or know that you’re going to do something with it.”

* * *

As Eaton Hemp came into its own and the hemp crop expanded at JD Farms, Justh and Dolgin were looking at the big, emerging players in the hemp food space, like Manitoba Harvest. “We were thinking, ‘OK, there’s an industry here, and we are first to market in the U.S.’ Obviously, things are happening in other states, but the beauty of where we are in New York was that we’ve got 20 million people downstream.”

Of all the possible end uses for the varieties of hemp they were growing, Justh and Dolgin knew they had to zero in on a legitimate marketplace to continue the business. D’Alessandro’s background was key.

“The beauty and the challenge of hemp,” Dolgin says, “is that it lends itself to basically any product you could imagine because the hemp seed can be pressed for oil, grown for flower or just kept whole or de-hulled.” They began developing different products, taste-testing this and cooking up that. The 2018 Farm Bill was coming into view, and so too was the organic hemp food market on a broad scale.

With D’Alessandro guiding the development of the Eaton Hemp brand and the message behind the company, the team tooled around with possible ideas: pancake mix, pizza crusts, raw bars, crackers. They co-branded a line of Sfoglini pasta out of Brooklyn using hemp flour from Eaton Hemp, “which was nice just to kind of test the market,” Dolgin says. The pasta line partnership continues to this day.

And in the greenhouse, where the team runs R&D work on a CBD variety breeding program, Justh and Dolgin also experimented with the leaves of their hemp plants.

“The other real surprise and revelation was that the leaves of the plants at a young age taste really good,” Dolgin says. “I mean, not bitter at all. Nutty and buttery. And if there was a bitterness, it was a natural deliciousness to it and not an overwhelming aspect.”

They sold baby greens to ABC Kitchen in Manhattan in 2017 and 2018 and toyed around with the various angles into hemp as a food product.

“What we’ve really started to build is more of a lifestyle brand than anything,” Dolgin says, “and trying to really steer ourselves in that direction and get this in the hands of athletes and doctors and folks who are in the health and wellness space is really what at least the beginning part of this year is definitely going to be for us.”

Justh and Dolgin talked to regional managers at Whole Foods and other big box retailers to find out what product categories were moving. The long game was coming into view.

“We look at the farm as kind of a blank canvas, and then we kind of add all the paints and the textures and things like that,” Dolgin says. “We knew with our network and our contacts that we could bring in the right people and really develop something that was interesting that really played into the taste and flavor profile. … What we found when we started looking at other players in the market was that most of what was happening in the hemp food space was still in the big bag, commodity bulk products like Hemp Hearts and flower. And we wanted to take more of an elevated value-add or premium approach.”

The key was to keep the spotlight on hemp, rather than hiding it somewhere on the tail end of an ingredients list.

And ever since moving from ruminations on cover crops to the company’s sprawling work in the organic hemp food space, the team behind Eaton Hemp knows that’s where the spotlight belongs: on this crop.

The policymakers in New York state seem to know this, too. JD Farms was a 2017 winner of one of the state’s $1 million Industrial Hemp Processors Grants, part of a broader funding platform for the industry in what’s considered a promising state. (More than 18,000 acres of hemp were licensed statewide in 2019.)

But the question now is where all of this is headed. Dolgin worries about a false sense of security for farmers who don’t yet have a plan or a market in place for their hemp.

“A lot of people are hearing these fantastical stories and wanting to put their entire farm [into hemp], and sometimes you kind of have to save farmers from themselves, and I think the state is now realizing that,” Dolgin says. “So, they propped up the industry, but they also have to help them kind of set some realistic expectations.”

That’s the story of hemp in early 2020: learning how to set expectations in line with supply and demand curves that haven’t yet settled into predictable patterns. Most eyes are turned to the CBD extraction market. Justh and Dolgin say they know enough to keep one eye on that segment’s emerging trends, but hemp is already proving to be a formidable agricultural force.

“We were looking at all aspects of the plant,” Dolgin says, “and realized at that point, to carry on the paint analogy, that by throwing paint at the canvas and seeing what sticks, we could learn what looked right.”