Linda Noel didn’t sell a single ounce of the hemp she harvested on Terrapin Farm in 2019. The entire 17-pound harvest—plus the small portion of her 2020 harvest that didn’t go hot—is vacuum-sealed and stored in her freezer.

Thanks to an oversaturated market, Noel, who received her hemp license in 2018 and grows plants in two 3,500-square-foot greenhouses, is hesitant to plant a 2021 crop on her Franklin, Mass., farm until she can sell her stockpile.

“Massachusetts had a massive oversupply because there wasn’t enough of a market,” explains Noel. “Most growers grew hemp for [cannabidiol] flower only to find out we couldn’t sell it.”

Oversupply is a national issue in the U.S. Excess biomass averages 24,795 pounds per farm—or 135 million pounds nationwide, according to “Déjà vu: An Economics Analysis of the U.S. Hemp Cultivation Industry,” a 2020 report from the Portland, Ore.-based consulting firm Whitney Economics.

The Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 (the 2018 Farm Bill) removed hemp with less than 0.3% tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) from the list of Schedule I drugs under the Controlled Substances Act, providing opportunities for growers to begin cultivating the once-prohibited crop, and it sparked massive interest.

The number of acres of hemp grown increased from 78,176 in 2018 to 201,126 in 2019, according to Vote Hemp, an industry advocacy organization. Many hemp growers produced crops without contracts, and the glut of available biomass led to a price crash. A Hemp Benchmarks report found that the price for up to 25,000 pounds of cannabidiol (CBD) biomass sold for $4.02 per percent CBD per pound in June 2019; seven months later, the price fell to $1.31/%CBD/lb.

Growers recognized the issue and scaled back operations. Vote Hemp reported that the number of licensed acres decreased from 511,442 in 2019 to 336,655 in 2020—and just 70,530 acres of hemp were planted last year in an effort to correct the oversupply problem. But the problem remains.

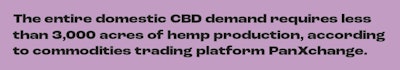

In fact, PanXchange, a commodities trading platform that provides baseline prices for hemp, estimates that meeting the entire domestic CBD demand requires less than 3,000 acres of hemp—or less than 6 million pounds—of hemp production per year. Despite the reductions in acreage, PanXchange’s calculations show growers are still significantly overproducing hemp—and with two years of hemp in storage, Seth Boone, PanXchange’s vice president of business development, expects the 2021 acreage to decline even further.

But solutions do exist. As growers struggle with oversupply, these six strategies may help producers, lawmakers and other industry stakeholders deal with stored biomass and alleviate the issue for seasons to come.

1. Leading With Legislation

Although the 2018 Farm Bill paved a path for legal hemp cultivation, the industry remains plagued by regulatory confusion. Some current legislation—or lack thereof—is contributing to the oversupply problem, according to Ryan Quarles, president of the National Association of State Departments of Agriculture (NASDA).

“In 2018, the biggest thing holding hemp back was its legal classification as a controlled substance,” he says. “The 2019 crop year created an influx of growth, … and one of the reasons [growers] continued to move forward knowing there would be increased supply was the belief that the Food and Drug Administration [FDA] would promulgate and release a legal framework for how their legally produced and processed hemp-derived products could be sold in America. The FDA has yet to act.”

Quarles calls the lack of legal framework a “chokepoint” that is creating an issue with oversupply and preventing the hemp industry from flourishing. FDA guidance on how CBD products like tinctures, oils and infused foods and beverages would be regulated is key to addressing the stockpiles of biomass from the past two seasons, he adds.

“The market is experiencing a correction … as growers continue to struggle to understand what FDA oversight might look like [because] they don’t want to get sideways with the law,” he says.

But, it’s not just the lack of federal regulations that are contributing to excess biomass. In some states, local jurisdictions make their own laws governing CBD sales, dictating where (and if) it can be sold and which age groups can consume it. Those local restrictions, along with regulatory uncertainties, have impacted available markets.

In an attempt to address the oversupply and create new markets for hemp farmers, states such as Illinois and Colorado have passed legislation permitting hemp growers to sell their crops to legal marijuana dispensaries. In 2020, lawmakers in Massachusetts passed similar legislation, which was the sole reason Noel renewed her hemp license this season; but she’s waiting for the legislation’s final regulations to be issued before she puts a single clone in the soil. (That legislation was expected to take effect in March, but “so far, Massachusetts’ Cannabis Control Commission has yet to administer an update, guidelines or even a timeline,” as HempGrower.com reported on March 19.)

“If [Massachusetts] can roll out the regulations in a timely manner, we could have a very good year,” Noel says. “If we have an in-state market that’s going to allow them to receive premium prices for their crops, it’ll be way better for Massachusetts farmers.”

2. Getting Creative With Sales Models

Limited processing capacity has also made it difficult for growers to get their harvests to market. Whitney Economics called processing capacity the “biggest factor affecting the hemp market,” noting the 3,179 processors licensed nationwide would have to process 900 pounds of biomass per day to keep pace with licensed capacity; most processors only had the capacity to process 90 pounds per day.

The lack of processors has led some growers to opt out of the traditional supply chain. Their preferred route: Direct-to-consumer sales. Some growers even have established U-pick operations, inviting consumers to harvest their own hemp right on the farm.

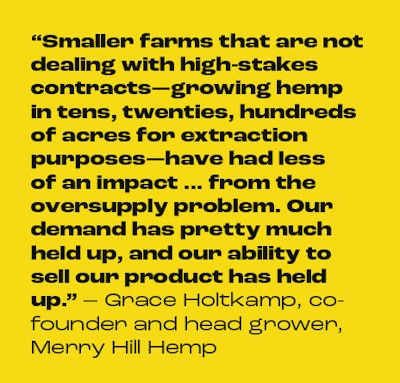

“The early messaging to growers was ‘grow big or go home,’” notes Grace Holtkamp, co-founder and head grower at Merry Hill Hemp in Mebane, N.C. “It’s the large-scale farms that are relying on contracts and extraction that have faced more of the challenges. [The issue with oversupply on larger farms] has really reaffirmed our decision to focus on getting the flower to the people.”

Holtkamp started growing CBD floral hemp in 2017 and opened Merry Hill Hemp. The decision to invite consumers to harvest their own CBD flower has allowed the farm to thrive, Holtkamp says; the 2019 and 2020 harvests sold out. Holtkamp even increased her prices last year, and she expects a similarly successful 2021.

“Smaller farms that are not dealing with high-stakes contracts—growing hemp in tens, twenties, hundreds of acres for extraction purposes—have had less of an impact … from the oversupply problem,” she says. “Our demand has pretty much held up, and our ability to sell our product has held up.”

As oversupply has become more of an issue, Holtkamp is fielding an increasing number of calls from growers looking to transition to a direct-to-consumer or U-pick models.

“What we have seen on our farm is different than what the industry discusses when they talk about an oversupply. Each year has been more profitable and more successful, [and] we’ve really hit all of the metrics that we wanted to,” she says. “I hope large-scale continues [but] I do think people are going to start running more small-farm models for this crop as well.”

3. Expanding Exports

The U.S. market for hemp is hard to measure, according to Boone. Producers can use myriad export codes—called harmonized system, or HS, codes—to tag products for tracking. But because CBD can be tagged in many different categories (with different codes), it is difficult to track the quantities of CBD leaving the U.S. for other countries.

A Hemp Benchmarks report found that exports of smokable hemp destined for Canada, Europe, the Middle East and Asia have “increased significantly” since 2019. Some shippers are reporting that prices on the global market are much higher than domestic prices, making international sales attractive to growers—especially those with excess hemp to sell.

Exporting hemp could help address oversupply, according to Boone, but he acknowledges “it’s probably a drop in the bucket for the amount of material we need to move.”

There are efforts to build an export market for hemp, though doing so may take longer than those with excess biomass would like. The “2019 Hemp Annual Report” from the United States Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service (USDA-FAS) notes, “While China is currently not a major import market for hemp, potential exists if regulatory barriers can be addressed. [But] this potential is several years away from coming to fruition. Importation of CBD is banned and only a negligible amount of fiber was imported in 2018. Nonetheless, the industry envisions this changing rapidly as the national government recently approved CBD for cosmetic use.”

In 2020, USDA-FAS awarded a $200,000 grant to the National Industrial Hemp Council (NIHC). This Market Access Program funding allows USDA-FAS to partner with domestic trade associations, trade groups, cooperatives and small businesses to share the costs of building commercial export markets. NIHC’s emphasis is on markets in Europe and China, two geographic regions driving the global hemp market.

4. Shifting Away From CBD

Growing for other novel cannabinoids could also help hemp growers capture market share and prevent hemp harvests from going unsold. Seed and clone prices for varieties high in one cannabinoid, cannabigerol (CBG), have increased every month between January and April 2021, according to Hemp Benchmarks. The company estimates that about 5% to 10% of cannabinoid hemp grown in the U.S. in 2020 was for CBG production, with most of the rest going toward CBD and small portions being dedicated to other minor cannabinoids. (Hemp Benchmarks first started hearing about CBG during the 2019 growing season, says its editorial director, Adam Koh.)

Hemp Benchmarks’ Price Contributor Network reports varying degrees of demand across the country for this cannabinoid. While some have reported an increase in demand, assessed prices for CBG have decreased from $6.07/% CBG/lb. in April 2020 to $0.89/% CBG/lb. in April 2021.

A shift away from CBD may not address the glut of biomass remaining from 2019 and 2020, but it could prevent this season’s harvest from languishing, unsold, in storage.

However, Holtkamp worries cannabinoids like CBG and delta-8 THC could be the next fads, which could contribute to future oversupply.

“Growing hemp for CBD use has become a lot more complicated because of these fads of different cannabinoids,” she explains. “Last year, everybody was still getting to grips with the cannabinoid delta-9 THC. Now we have a surge in popularity of delta-8 THC. …We are purely growers and don’t want to involve ourselves as much in those types of trends because of the risks.”

Growing for grain and fiber markets could also provide hemp growers with important markets for their crops. A report from market analyst New Frontier Data (NFD) shows that U.S. hemp fiber production volume exceeded processing capacity in 2020 (for more on this, see And Counting ), however, the market segment has potential to see significant growth. Hemp food product retail sales hit $67.1 million in 2020, while wholesale processed hemp fiber hit $47.1 million last year, according to NFD. The company projects the 2025 retail market for hemp grain could top $144 million, while the wholesale market for fiber could hit $82 million during the same period.

In Canada, Jeff Kostuik, director of agronomy support for Hemp Genetics International and HPS Food and Ingredients, believes the strong grain and fiber markets have prevented oversupply issues.

“Different areas within the country are more interested [in grain and fiber],” Kostuik says. “Southern Ontario, which is very similar to Kentucky and Tennessee, had a tobacco industry, and producers in that area are looking for something to replace that.”

A current lack of infrastructure and an underdeveloped supply chain on this side of the border could hamstring, at least temporarily, the development of those industries—and transitioning from growing for cannabinoids to grain or fiber crops might not be feasible for smaller growers.

In Massachusetts, for example, Noel notes, “Most of our growers are limited in land size and have no choice but to grow for cannabinoids. I don’t have the acreage to even consider grain.”

For growers with more acreage and access to infrastructure, a pivot to fiber and grain might not reduce the current stockpile of biomass, but it could help prevent future oversupply.

Some growers, committed to hemp but frustrated with the market saturation growing for CBD, have started transitioning. In Montana, for example, 80% of hemp producers grew for CBD in 2019 (a major shift from all licensed hemp producers growing for grain in the prior year). But in 2020, that changed again, and a whopping 85% of licensed acres in the state were dedicated to grain and fiber production, according to state agriculture officials.

5. Weighing the Risks of Converting to Delta-8

The emerging popularity of delta-8 THC, a minor cannabinoid that is synthesized from CBD and delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol, and sold in dispensaries, CBD shops, gas stations and online, has offered growers some hope for moving biomass. While some, like Holtkamp, worry it is the next fad, it may present an opportunity for farmers who currently have unsold inventory.

In fact, a 2021 PanXchange analysis noted that delta-8 THC sales were “needed” to work through the hemp oversupply. However, growers and processors should proceed with caution on this front, as some debate still exists around the cannabinoid’s legality and ethics. (Some states have already banned it; more on this below.)

Processors are currently buying flower and distillate to make the sought-after compound, but Boone notes there is little data on how much biomass is moving to the delta-8 market.

“On paper, using a common conversion rate, … we’d need 1 million kilograms of pure delta-8 distillate to clear the market out,” he explains.

Boone believes growers must take extra care to produce top-quality products that will not raise the ire of lawmakers about quality issues.

“Delta-8 is good for cannabis as a whole, but we have to go about it the right way, especially because it’s not regulated. We have to prove to the government that we’re going to be responsible [about producing delta-8 THC]. Right now, the quality of the product that can be found on the market today is a problem,” Boone says, adding inaccurate advertising regarding delta-8’s purity currently permeates the marketplace.

With a focus on producing delta-8 THC ethically, Boone believes “it could take out the oversupply.”

In addition to helping farmers sell stored biomass, converting to delta-8 THC could also boost revenues. Data from Hemp Benchmarks show the prices for the distillate were far higher than and sometimes exceeding average marketplace prices by “several thousand dollars” compared to CBD and CBG distillates.

The solution, however, might be short-lived. As of press time, 12 states—Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Delaware, Kentucky, Idaho, Iowa, Mississippi, Montana, Rhode Island and Utah—had banned delta-8 THC, and similar legislation is moving through several other states. The U.S. Hemp Authority has also declined to certify delta-8 products. These actions have limited growers’ opportunities to sell biomass into the delta-8 THC market.

Hemp Grower has also spoken with industry sources who say delta-8 THC may fall within proposed Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) regulations classifying “synthetically derived tetrahydrocannabinols” as Schedule I controlled substances. However, the DEA did not explicitly name delta-8 THC in its interim rule, so speculation remains over whether the cannabinoid is considered “synthetic,” making it a potentially risky market.

6. Selling First, Growing Later

Growers who planted seeds and clones without a contract to sell their crops often took the biggest hit in the market. Kostuik believes most growers have learned their lesson and are focused on selling their crop, then growing it.

“All through my hemp career, I’ve been encouraging people to make sure that they have a home for their product, whether it is grain or fiber or CBD,” he says. “More producers are aware of that moving in. [Growers] aren’t just throwing in hemp because it’s cool and thinking, ‘hemp’s legalized, let’s plant it and then figure out what to do with it.’ Now, their thinking is, ‘OK, what are we going to do with it if we plant?’”

After three years of “planting on faith,” Noel is not planting a single clone until she has a contract; she hopes that growers planting hemp in 2021 and beyond take the same approach, especially when the laws are constantly in flux.

“Massachusetts had an oversupply problem … because there wasn’t enough of a market; most of the cannabidiol growers grew for flower only to find out that we weren’t going to be allowed to sell it [due to state regulations],” she says. “Processors are willing to take [my oversupply] if I’m willing to let it go, but they are paying $40 per pound for biomass and, at that price, I’d be selling at a loss. This year, I have to have a contract before I’ll commit.”

Dealing with the hemp oversupply from the past two seasons will take time, and different growers need different strategies to offload the glut of biomass. As stockpiles dwindle, growers must also be focused on preventing a recurrence.

“The speed at which new states have been able to benefit from existing frameworks [for hemp production] means that [states] can be issuing far more licenses for both growers and processors [and] increasing their capacity,” Holtkamp says. “The competition is intense because the supply has increased and these newer programs are getting onboarded so much quicker, [but] I do think there will be an increase in craft [hemp] for farmers who can reset their focus … rather than seeking out a one-off big contract.”