The cost versus reward of hemp production in the U.S. is constantly changing, making each production decision a pertinent one, including deciding whether to start with seeds or clones.

Goal-oriented breeding (or breeding for a specific outcome) is advancing thanks to regional data collection. This has resulted in higher quality clones that, in some cases, surpass the performance of seed.

Breeders select clonal material regionally to provide consistency. Additionally, this material can be cleaned and screened through tissue culture, which is the aseptic process of growing plant cells in a controlled environment. Proper tissue culture methodology and screening can guarantee sterile plants, while seeds have potential to harbor disease internally and/or externally. However, the tissue culture process can be expensive and time-consuming.

Keeping in perspective the drop in biomass prices, are producers incentivized to purchase these higher-quality options over the less expensive seeds to sow? Let’s take a deeper look.

Like most mature horticultural markets, the quality of genetics highly influences the rest of the supply chain and, in many cases, the market strategy for the crop. Many farmers start with seed and stay with seed. Others use seed and rooted and unrooted vegetative material, and they may even progress into tissue culture.

According to numerous federal and industry sources, the U.S. hemp market grew from approximately 78,000 acres in 2018 to around 400,000 acres across 47 states in 2020. This explosion in growth saturated the market with plant material (biomass) rich in cannabidiol (CBD), causing the value of biomass to drop significantly. Looking at the value of hemp rooted clones (hemp liners) during the past three years can help us understand this market progression.

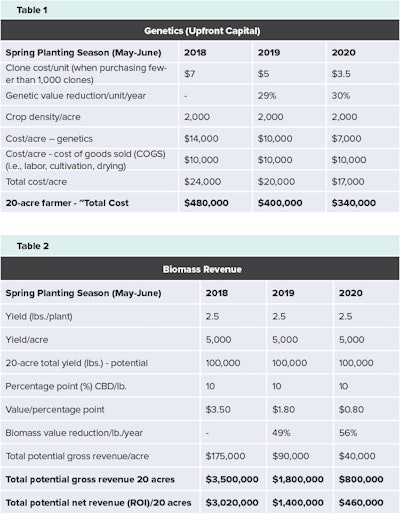

For example, Table 1 shows the costs associated with buying hemp rooted liners for field CBD production for The Hemp Mine, a 60-acre farm in South Carolina. In this example, the price drops 50% from 2018 to 2020 for the same hemp liner with other production costs staying fixed.

To justify the value of hemp liners, whether it be $7 or $3 per unit, there needs to be a practical return on investment (ROI). To properly calculate the value of CBD biomass, the metric must be based off the dry-weight percentage of CBD in a single pound of biomass.

In Table 2, we are considering this material as dried down between 8% to 10% moisture content with an average potency of 10% CBD per pound. The market value of CBD shown here went from $3.50/%CBD/lb. in 2018, dropping drastically to $0.80/%CBD/lb. in 2020 based on what we have secured while conducting business at The Hemp Mine. This would make the value per pound $35 in 2018 and $8 in 2020. Table 2 shows predicted ROIs associated with these different values per year, starting with the exact same initial plant material.

Prior to spring 2020, the predicted ROI was as high as $23,000/acre. However, over the course of the year, the value of CBD decreased even more. Where we were predicting a steady value of no less than $0.80/%CBD/lb., we are now falling as low as $0.30 to $0.50/%CBD/lb., making a single pound worth as little as $3.

Seeds Versus Clones

Seed, on the other hand, presents a cheaper alternative to clones. Over the past three years, seed has been ever-present in the market, being sold through multiple sources, including breeding companies, brokers and distributors. Most of these varieties are open-source genetics (not containing intellectual property). They can be non-feminized or feminized and have variable germination rates. The cost for these vary, but generally, non-feminized seed prices are significantly less than the average cost of around $1.50 per feminized seed, according to Hemp Benchmarks.

At first glance, this seems like a no-brainer to choose seed over clones, but it is not that simple. We’ve seen numerous horror stories of farmers going out of business due to their seed crop going “hot” (meaning testing above the legal 0.3% THC limit), extreme crop heterozygosity (varying phenotypes), pollen drift from male or hermaphroditic plants, poor germination rates, and other seed-related issues. A handful of companies in the market are supplying decent-quality seed, but it still is risky.

Given the predictability but higher cost of clones, and the cheaper but higher risks of seed, where will the hemp industry go from here?

Seed is inevitably the future for outdoor cannabinoid production destined for extraction. Nothing makes more financial sense than mechanically sowing seed with a 99% germination rate and then mechanically harvesting. Despite the need for further development of seed lines for truly homogeneous hemp crops, slight inconsistency is acceptable, especially with seed prices continuing to drop.

That said, oil production is not the only reason to grow hemp. Consider indoor/greenhouse production for smokable flower. With returns of $150 to $350 per pound for smokable flower in The Hemp Mine’s experience, highly predictable and consistent clones will be sought out and expected as they would in the cannabis industry. This indoor sector of the industry will continue to use vegetative material for the extended future.

Seed is the future, but it is not practical to think homogenous lines can be formed overnight. This is a work in progress that will take time and trials across environments. Until then, there is value and reason to choose consistent, uniform and predictable genetics.