When the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA’s) Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS) published its final rule on hemp production in January, industry stakeholders wondered just how “final” the pending regulations really were. Since the rule took effect March 22, growers are starting to understand how these changes will impact their operations and the industry’s fate moving forward.

“The publication of the final rule is an important step in providing regulatory certainty for the hemp industry and providing stability and consistency to hemp growers in order to reduce crop loss,” a USDA spokesperson tells Hemp Grower. “USDA worked hard to incorporate the feedback received during two open comment periods prior to issuing the final rule, and we remain committed to working with the industry to fully understand the needs of this emerging crop.”

After fielding 5,900 public comments and hundreds of feedback sessions with various industry groups, the USDA made several key changes that differ from its 2019 interim final rule (IFR). While some modifications came as a relief to growers, certain regulatory burdens remain as growers wrestle with the challenges that lie ahead in the coming seasons—specifically when it comes to sampling and testing protocols that could make or break a hemp business.

To understand the final rule’s implications on testing protocols, Hemp Grower spoke with industry members about these newly approved regulations and how they could help standardize hemp production moving forward.

Sticking to the THC Limit

Rory Cruise cultivated 950 Stormy Daniels plants in Pleasanton, Neb., in 2020 as one of the state’s first licensed industrial hemp growers. “I would have had a really good crop,” says Cruise, CEO of Sweetwater Hemp Co. Unfortunately, his plants tested “hot” above the legal limit of 0.3% tetrahydrocannabinol (THC).

As soon as his plants began to flower last summer, Cruise started sending samples to the lab. His first test revealed a THC concentration of 0.19%—well below the limit.

“I decided to do another test because I wanted to see the data curve as [the THC level] went up,” Cruise says. “I pulled a sample the next week, overnighted it [to the lab], and after a three- or four-day turnaround to get the results back, I was already at 0.27% [THC].”

Cruise immediately called the Nebraska Department of Agriculture (NDA) and submitted the necessary paperwork to schedule his compliance test—which had to be completed 15 days prior to harvest, according to the IFR. But, by the time the state sampling agent arrived 10 days later, it was too late. Sweetwater Hemp’s results registered 0.36% THC, just over the legal limit.

“It was a huge disappointment,” says Cruise, who had to destroy his entire crop under the watch of an NDA agent and a state investigator. “I had to cut it all down and lay it out, and then they watched me shred it with the mower until it was all gone.”

Sweetwater’s devastating first season exemplifies the heavy regulatory burdens on growers in the fledgling hemp industry as they battle unpredictable conditions and strict testing requirements that make the 0.3% THC threshold seem “impossible, the way the rule was written,” Cruise says. “To make this a valuable crop in the U.S., we need that [THC limit increased to] 1% ….”

When the final rule took effect in March, Cruise was “concerned” to see the 0.3% limit remain unchanged. But since this cap is written into the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 (the 2018 Farm Bill), it falls outside of the USDA’s jurisdiction. Amending it would require congressional action—which Senator Rand Paul of Kentucky has proposed through his Hemp Economic Mobilization Plan (HEMP) Act of 2021. Paul’s HEMP Act, which he reintroduced in March after the final rule took effect, would increase the national THC threshold to 1%.

The 0.3% cap originated from a research article published in 1976. Even then, the authors noted they chose that limit “arbitrarily” as a means of distinguishing hemp from marijuana. In early 2020, research from Cornell University’s School of Integrative Plant Science shed more light on this figure, suggesting CBD and THC are locked together in a set ratio—meaning if hemp plants are confined to 0.3% THC, then the CBD levels are inextricably confined as well.

“The 0.3 is the killer,” says Robert Mills, Jr., president of Briar View Farm Inc. in Callands, Va., where he grows hemp, tobacco and other crops while raising cattle and poultry. “You get paid on [the level of] CBD, and you need to be at 8%-13% CBD to make money. But to do that, you’re going to push the THC all the way to the limit. You can’t change that limit without changing the farm bill ….”

Despite this hotly contested issue, Cruise was “super excited” to see other key changes in the USDA’s final rule that might alleviate this burden by giving growers more flexibility around testing timelines, sampling procedures and handling non-compliant crops.

“Many hemp growers are consistently stressed out about the level of THC and whether their plants will test hot or not,” says Roger Brown, co-founder and president of ACS Laboratory, a cannabis and hemp testing laboratory in Sun City Center, Fla., that uses the ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) method to test the potency of hemp flower samples. “Several of the changes to the rules will actually help producers [who are concerned about] testing hot.”

Expanding the Sampling Window

One of the biggest changes in the final rule was the increased sampling window, which doubled from 15 to 30 days prior to harvest. This means farmers must schedule to have hemp samples collected by state agents for THC testing within 30 days of their planned harvesting date.

The expanded window gives regulators more time to collect samples from each producer, and it also gives growers more time to complete their harvest after testing.

“During the comment period, stakeholders requested greater flexibility during the sample collection phase because many hemp fields in their state are harvested at the same time,” a USDA spokesperson says, citing strained state resources and delays getting test results back from labs as reasons for this change.

Since THC levels rise as hemp plants mature, this valuable window of time before harvest can make or break a crop. Knowing precisely when to pull the trigger for testing can be a challenge for growers grappling with the THC curves of new genetics, so this extra time comes as a relief.

“I was really happy to see the 30-day window. It’s going to take a little bit of stress away from farmers,” Cruise says. “I saw a lot of guys who pulled their crop super early last year because they were worried about going hot, and even after 15 days, it wasn’t even close [to maturity]. Now that they have 30 days ... to allow the crop to finish maturing, that’s a gamechanger.”

“Having a 30-day window gives us a little more room to watch the plant and make sure that it doesn’t go above 0.3[% THC],” says Mills, who starts pulling samples for potency tests as soon as his hemp plants begin to flower, so he knows when to schedule his official state compliance test. “The problem we have as growers is, it’s $50 [or more to test] a sample, and every variety we grow has to have a separate sample. Next thing you know, you’ve spent $400 trying to stay within that 0.3% THC limit.”

However, Brown recommends that growers view the cost of testing as “an insurance policy you buy against the product turning hot,” he says. “The closer you are to harvest, the harder it is to hit below 0.3%. Increasing the window between testing and harvesting allows growers to prepare more by doing potency tests along the way.”

Adding Flexibility

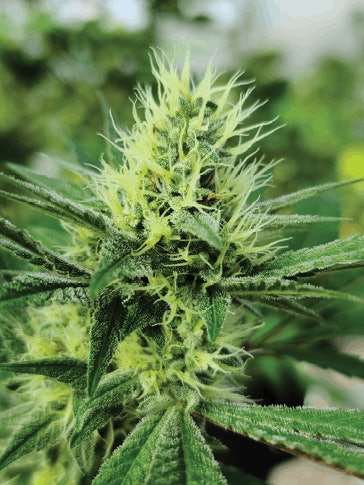

The final rule also modified several sampling protocols, giving growers and regulators more flexibility in the process. While the IFR required samples to be clipped from the top third of a plant, the final rule states samples can be collected by cutting “the top 5 to 8 inches from the ‘main stem’ (that includes the leaves and flowers), ‘terminal bud’ (that occurs at the end of a stem), or ‘central cola’ (cut stem that could develop into a bud) of the flowering top of the plant.”

This change allows sampling agents to collect more stem and leaf material, which typically contains lower levels of THC and other cannabinoids than the flowers.

“If [the sampling agent] grabs a plant that doesn’t have a lot of fan leaves by the top cola, that one’s going to be [higher in THC] than the next one that has a few more fan leaves,” Cruise says. “Sampling more of the plant, instead of just going after the hotspot, is definitely going to benefit the farmer.”

However, this still requires sampling primarily floral material, despite the plethora of public comments that called for a whole-plant sampling approach.

“If we’re going to take all these flowers [from the whole plant] and put that material in a box, all mixed up, then why are we not taking clippings from the bottom, middle, and top?” says Mills, a member of the state board of directors for the Virginia Farm Bureau. “The sample needs to be a random sample of the profile of the plant. I don’t think that’s too much to ask when you’re talking about a plant that either passes or gets destroyed.”

Even more significantly, the final rule allows states and tribes to adopt their own “performance-based sampling methods” instead of requiring that plants from every single field of every producer be tested, as in the standard protocols established by the IFR. These tailored sampling methods might consider a producer’s compliance history, seed certification processes for compliant hemp varieties, or other factors

States must include these performance-based sampling methods in their hemp plans to be approved by the USDA. (Updated sampling guidelines that detail how to select, cut, and store hemp clippings are available on the AMS website.)

The final rule also loosened the negligence threshold from 0.5% to 1%, which means hot hemp will not be considered a negligent violation if it tests above 0.3% but below 1%. The final rule clarified that growers can only receive one negligent violation per year. After three negligent violations in a five-year span, growers will have their license revoked and won’t be eligible to participate in the hemp program for another five years.

However, the increased threshold doesn’t change the fact that hemp testing over the 0.3% limit must be either remediated or destroyed.

To soften the blow of hot crop loss, the final rule provided some additional options beyond the total destruction that was previously mandated by the IFR.

The final rule introduced remediation options that allow growers to recuperate some of the crop’s value. These expanded options include:

- Removing and destroying the flowers, where THC is typically concentrated, while retaining the rest of the plant material to sell, or

- Shredding the whole plant to create blended biomass material that can then be retested for THC compliance—following the same procedures used to conduct an initial test.

Following a non-compliant test, hemp producers now have more flexible on-farm disposal options, too. Instead of requiring U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) agents or law enforcement officers to be present, the final rule allows producers to mulch, shred, burn, till, or bury it themselves. The AMS provides guidelines for acceptable disposal and remediation techniques on its website.

Testing at DEA-Registered Labs

The final rule retained the requirement for hemp testing laboratories to be registered with the DEA, since these labs might handle material with THC levels above 0.3%—which, by the legal definition, would be considered cannabis, a Schedule I controlled substance. After delaying this requirement last year, the USDA further extended the deadline to Dec. 31, 2022, allowing more time for labs to complete the rigorous certification process.

With fewer than 80 DEA-registered labs in 29 states as of April 1, according to AMS, some growers worry this requirement will severely limit their testing options, creating backlogs and long wait times that could impact their results.

“I’m hoping this will give them an opportunity to get more labs certified so there’s no bottleneck on the testing,” Mills says. “We can’t go much more than three days [to get test results back] because once that plant starts reaching maturity, the THC level can change almost overnight.”

However, Brown doesn’t believe testing backlogs will be an issue, especially after the extended deadline. “The beautiful thing about hemp is that it’s federally legal, so you don’t have to have a laboratory around the corner from you—as opposed to marijuana, which can’t cross state lines,” says Brown, noting that ACS Laboratory receives samples from 48 states and maintains three- to five-day turnarounds. “There are plenty of DEA-certified laboratories that can handle the volume, and in the future, hopefully there will be even more.”

Brown emphasizes the benefits of using DEA-certified labs as a means of bringing much-needed standardization to the hemp testing industry. Although this requirement “doesn’t standardize the testing equipment or methodology,” he says, the final rule does mandate that labs use post-decarboxylation or “similarly reliable” methods that convert delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA) into THC to calculate the total THC concentration on a dry-weight basis. “I think that will help the growers because getting a DEA license shows that a laboratory is able to perform testing at a much higher quality level,” says Brown, noting that ACS Laboratory is DEA registered and ISO 17025 Accredited. “It will help create standardization and utilization of specific testing protocols that allow growers to get more consistently reproducible results.”

The regulation also requires labs to report the measurement of uncertainty, or margin of doubt surrounding test results. Although the IFR used an example of +/- 0.05% to allow for testing variance, the USDA’s final rule did not establish any specific parameters for this calculation. Sen. Paul’s proposed HEMP Act would standardize this margin by using +/- 0.075% as a baseline measurement of uncertainty.

The USDA website contains detailed testing guidelines for laboratories, as well as a directory of DEA-registered labs.

Having a Final Say

Now that the final rule has taken effect (pending a few extended deadlines), many growers agree that these regulations add some much-needed flexibility to reduce the regulatory burden. As state and tribal governments, along with hemp testing labs, start applying the changes, producers will likely begin to see the impacts of these changes.

Overall, the final rule underscores the need for more sophisticated planning at every stage of hemp production. “You have to be strategic about when you plant, when you test, and when you harvest,” says Brown, a board member of the Hemp Industries Association of Florida. “Hemp farmers need to be more sophisticated in how they plan their whole process. All these rules and regulations are pushing everybody to be more professional.”

By setting a federal standard for the fledging hemp industry, the final rule formalizes hemp’s transition out of the pilot phase and into a legitimately regulated business sector.

“The USDA rule brings consistency from one state to the next. When you can find continuity with testing methods from state to state, it puts people on a level playing field, and that’s what we need as growers,” Mills says. “Having a program where all states are equal makes us a better industry.”

While the final rule sets a national baseline for hemp regulation, it also gives individual states and Indian tribes “fairly broad flexibility to enact and manage their own programs,” says a USDA spokesperson. These individual plans can be more restrictive than the minimum USDA requirements—but not less.

For example, Nebraska’s plan for the 2021 hemp season still operates under the 15-day sampling window established by the IFR. Cruise says his state legislature won’t amend these details until it revises its hemp production plan for the 2022 season, so growers won’t fully appreciate the modifications made in the final rule until their state administrators catch up with the change. Likewise, the 20 states still operating hemp pilot programs under the Agricultural Act of 2014 (the 2014 Farm Bill) can continue doing so until Jan. 1, 2022.

“I know it says it’s the final rule, but it’s just a start,” Cruise says, pinpointing the 0.3% THC limit as the biggest issue begging for federal reconsideration. “There’s definitely a lot more room for improvement to move forward and to make hemp the next hot commodity.”

Sen. Paul’s HEMP Act addresses many of the remaining concerns that growers like Cruise have with the latest testing regulations. His proposed legislation would amend the definition of hemp by raising the THC limit from 0.3% to 1%, while reshaping the testing protocols altogether by testing final hemp-derived products rather than the flower itself. “[T]here is still work to do to prevent the federal government from weighing down our farmers with unnecessary bureaucratic micromanaging,” Sen. Paul said in a press release announcing updates to his HEMP Act in March. His proposed changes, he said, “will help this growing industry reach its full economic potential.”

Until then, Mills advises growers to work closely with regulators to understand and improve the industry standards. Further change, he says, is inevitable.

“You can’t tell me that two years into a brand new industry, you’re going to put something in place that’s going to stay the standard for the next five years,” Mills says. “You’d be foolish to think that, and hopefully USDA will make the necessary amendments that need to be made as the industry evolves.”