In many ways, California is the cannabis hub of the U.S. It has the largest licensed cannabis market in the world, and its Emerald Triangle region presents fertile conditions nearly perfect for cultivating the crop.

But the story is not as ideal for cannabis’s federally legal cousin in the state. Despite picturesque growing conditions, hemp cultivators in the state face a plethora of other challenges, from navigating complex and ever-changing regulations to grappling with operating alongside some of California’s most thriving industries.

In fact, Richard Rose, a hemp industry veteran who has worked in the hemp food industry for more than 25 years, dubbed California one of the most restrictive states in the entire country to grow the crop.

“California is the worst state in which to grow hemp. With thousands of medical grows, they don’t want hemp pollen floating around,” Rose wrote on his website, The Richard Rose Report.

Slow-Moving Regulations

California’s hemp program experienced a sluggish start. The state first legalized hemp cultivation in 2013 with the California Industrial Hemp Farming Act. However, that bill contained a provision that stated growers could only cultivate hemp when it was “authorized under federal law,” rendering the act futile at the time.

It wasn’t until 2017—three years after the Agricultural Act of 2014 (the 2014 Farm Bill) legalized hemp federally for research purposes—that the state required its department of agriculture to develop a hemp program by way of Proposition 64, the same bill that laid out regulations for cannabis processors and growers. The bill included a requirement for the state to have an Industrial Hemp Advisory Board to recommend specific regulations and fees for the industry.

But a regulatory framework was not implemented until two years later in 2019, creating yet another holdup for growers.

“I’ve never seen a mess like this in all my years in working with other states on their hemp programs,” Chris Boucher, the current CEO of hemp consulting and genetics company Farmtiva Inc., told The Orange County Register back in 2019 as farmers awaited regulatory structure. He added that the state had “not made [hemp] a priority,” implementing cannabis regulations nearly a year and a half before hemp regulations.

The state’s current hemp regulations are mostly on par with federal laws. Notably, California has separate licenses for cultivators and “seed breeders,” each of which is $900 per year.

California implemented several new hemp regulations this year that help it align further with federal regulations. The biggest change was an emergency order that took effect in April to increase the sampling-harvest window from 15 to 30 days. This followed issuance of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) final rule on hemp, which made the same amendment on a federal level.

California submitted its hemp plan to the USDA in September 2020, and it is still currently under review. However, Steve Lyle, spokesperson for the California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA), says the “CDFA is currently working to determine if additional amendments to regulations are necessary to ensure approval of California’s hemp regulatory plan by USDA.” He confirms the state will be re-submitting a plan now that the USDA has issued its final rule.

But controversy over state laws comes into play with Assembly Bill 45/Senate Bill 235, companion bills that would allow the sale of hemp-derived cannabidiol (CBD) as a food, beverage, and dietary supplement—while simultaneously banning the sale of smokable hemp flower. The bills contain other controversial provisions, such as wrapping the state’s Bureau of Cannabis Control (BCC) into regulating hemp end products and implementing additional fees for hemp manufacturers.

Some organizations, such as U.S. Hemp Roundtable, support the bill. But others think the tradeoff for CBD isn’t worth giving up smokable hemp, which has proven to be the most lucrative market for hemp farmers as prices for CBD plummet. The BCC’s involvement has also left some opposing the bill.

“We’re fighting tooth and nail to not have [the BCC involved]. This is a USDA crop, period. You wouldn’t do this to tomatoes or potatoes,” says Wayne Richman, founder and president of the California Hemp Association. “How about this—why don’t we just start taxing grapes as if they’re wine because they have the potential to be wine? That’s exactly what they’re trying to do here with hemp.”

Complicated County Bans

As growers deal with lagging regulations, they face another obstacle: pushback from other industries.

Besides the state’s prioritization of cannabis (an industry that is taxed at multiple points of sale in the state), California’s hemp and cannabis industries bump heads over several other points of contention, Richman says. Cross-pollination is one issue—cannabis growers worry hemp cultivators’ grain crops could pollinate their plants and interfere with cannabinoid production.

There is also the potential of competition between the industries for products such as CBD and delta-8 tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), Richman says.

Hemp growers face opposition from another, perhaps unexpected, industry: wine and vineyards. Richman says some vineyard operators are opposed to both hemp and cannabis crops because of the smell.

Opposition from those industries has led to 27 of California’s 58 counties implementing restrictions, and some outright bans, on hemp, according to the CDFA.

These bans are not exclusive to hemp, as many California counties also prohibit cannabis operations.

But in some instances, the restrictions are exclusive to hemp, like in the case of Humboldt County. After continually extending a temporary moratorium on hemp production in the area, the county moved to completely ban hemp production in February. The Lost Coast Outpost reports that a majority of support for this ban came from licensed cannabis growers.

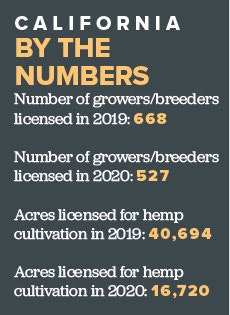

With the uniquely challenging situation in California, along with the various other challenges hemp cultivators face nationally, licensed hemp acreage plummeted from 2019 to 2020. But Richman remains hopeful that the state will eventually gain its bearings in the market as conditions improve.

“I know there’s going to be a lot less crops [this year], but I think it will turn the corner in the next year or two as infrastructure is built out,” Richman says.