© Oleksii Liskonih | iStock

Editor's note: An abbreviated version of this article ran in Hemp Grower's June 2021 print issue.

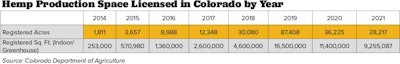

Seven years ago, Colorado blazed a new trail as the first state in the U.S. to launch a hemp pilot program following passage of the Agricultural Act of 2014 (the 2014 Farm Bill). Now, its industry is thriving with more licensed acreage than any other state in the U.S. in 2020, according to a Hemp Grower analysis. Last year, the state licensed 1,254 producers to grow 36,225 outdoor acres and 11.4 million square feet indoors and in greenhouses.

The reasons for this are plenty, from industry members’ growing and processing expertise to the positive relationship many of them have with state government, says Brian Koontz, hemp program manager at the Colorado Department of Agriculture (CDA).

The weather also helps. “Some of the growers I’ve talked to that have come out here from other states like California or the Midwest said the growing conditions are good here in the sunny West,” Koontz says. “It’s not too wet, so there aren’t disease or mold problems. It’s dry. Abundant sunshine.” He adds that hemp growers who move from lower elevations in California tend to experience less humidity, cooler night temperatures, and less insect and disease pressure.

The number of licensed hemp producers in the state increased every year between 2014 and 2019, from 259 to 2,812, according to CDA data. However, the number of producers decreased in 2020 due to the glut in the market that occurred in 2019 when growers flocked to cannabidiol (CBD) production. So far in 2021, fewer producers are licensed than at the same time last year, according to CDA data.

Dani Fontaine-Billings is founder of Colorado Hemp Project, a hemp consulting agency and seed and fiber supplier. The company grows and partners with farmers for a total of about 4,000 acres of outdoor hemp production in Colorado and another roughly 3,000 acres of outdoor production in other states. It also partners with greenhouses in California that have about 500,000 square feet of growing space.

In addition, Fontaine-Billings runs several other hemp companies: Nature’s Root, a body-care product line; Nature's Root Labs, a white and private label services provider; and Felora, a cat litter company.

Fontaine-Billings says Colorado has a cannabis-friendly culture. “It’ll always help push forward cannabis, anything related to the plant,” she says of state leadership. “So whether it be marijuana or hemp, it’s going to be pushing forward. They want to create opportunity and economic value. Boom, boom, there you go. You've got both right there for you.”

To an extent, Koontz says some cannabis growers’ expertise translates to the hemp market. “There are cannabis producers that do both types, hemp and marijuana,” he says.

How the Environment Dictates Growing Conditions

Hemp farmers have carved out their own niches in various regions of the state.

From fertile river valleys to desert plateaus, Koontz estimates the Centennial State has about five primary hemp-growing regions, including four primarily outdoor-growing regions where farmers have one crop cycle per year. These include:

- The Western Slope west of the Continental Divide, stretching down to the Four Corners area where the state connects with Utah, Arizona and New Mexico;

- The Arkansas Valley, where the Arkansas River runs between Pueblo and Lamar;

- The San Luis Valley, a region in south-central Colorado where the Rio Grande River runs;

- The South Platte River valley, extending from Denver northwest toward Sterling; and

- The Front Range, the populous middle of the state east of the Continental Divide including Denver, Fort Collins, Boulder and Colorado Springs, and featuring indoor and greenhouse production.

But it’s no secret that Colorado’s weather can be extreme. Drought, early snows and freezes, and massive hail can all damage or ruin hemp plantings, which Fontaine-Billings says is why she partners with growers throughout the state.

Koontz says other Colorado hemp growers protect themselves by being versatile in where they grow. The state’s legendary hail, which has been recorded as the size of golf balls, baseballs and even softballs, has ruined corn and wheat crops in the state, he says.

Because the weather is often dry—if not under outright drought conditions, as about four-fifths of the state currently is—producers of other, more water-demanding crops such as soybeans, corn and other grains have moved to hemp.

Irrigation practices such as center pivot systems contribute to the high acreage in the state. “When you go to pivots and you’re growing at 120, 160 acres a circle, we’ve got farms that are 900 acres or bigger producing hemp,” Koontz says.

Colorado’s low humidity is also a boon come post-harvest, Fontaine-Billings says. “You can leave it outside for the four to five days that’s needed [after harvest],” Fontaine-Billings says. “You can then turn it and leave it outside for another four to five days, and then boom, you can bale it up [without] having to deal with drying systems and extra costs at harvest.”

And winter weather can be a plus because growers rely on mountain snowpack and reservoirs for irrigation water, Koontz says, though he explains that hemp uses less water than some other crops and that growers in various regions of Colorado possess the water rights to successfully grow it.

Numerous western states rely on the Colorado River, but climate change has increased water scarcity in the region, according to researchers from Colorado State University and the University of California-Los Angeles. “We need to have really strong winters for agricultural purposes with the water because the Colorado River provides for multiple states, not just Colorado,” Fontaine-Billings says.

While the snowpack offers benefits for irrigation, Koontz says unpredictable winter-like weather events can be problematic. "Certainly, early snows ... [and] freezes at the end of the year can impact what hemp is ultimately harvested because we can get freezes as early as the first week of October," he says.

How the State Works With Growers

Koontz says Colorado state officials plan to more closely support the hemp supply chain through the development of a Hemp Center of Excellence. In the meantime, they have taken other steps to encourage evolution of the state’s hemp industry by working to improve access to goods and services, Koontz adds.

In 2019, for example, CDA partnered with 200 stakeholders and eight agencies on the Colorado Hemp Advancement and Management Plan (CHAMP) initiative. According to CDA's site, "a key objective of the CHAMP initiative will be to define a well-structured and defined supply chain for hemp in order to establish a strong market for the state's farming communities."

Colorado’s Department of Regulatory Agencies (DORA) and Office of Economic Development and International Trade (OEDIT) encourage economic development and manage business licensing and registration for businesses such as banks, credit unions and savings and loan associations. “DORA and OEDIT have been actively engaged with the financial industry to try to create easier ways for people in the cannabis market—for both marijuana and for hemp—to be able to participate,” Koontz says.

The state is also working with producers to increase the availability of decortication equipment, which separates hemp’s bast fiber from its hurd.

Exemplifying hemp’s transition into the mainstream textiles industry, clothing company Patagonia has chosen to grow hemp in the San Luis Valley.

“Patagonia partnered with the state last year to grow several hundred acres of hemp here under the thought of producing domestically produced organic clothing, and they are continuing to increase that project here in Colorado,” Koontz says.

Patagonia uses harvesting and decortication equipment from Formation Ag, a San Luis Valley-based company that Fontaine-Billings also says she works with.

Fontaine-Billings says processing for fiber, grain and hurd should be evenly distributed across the U.S. “It’s not just in regionals; it needs to be based super local, within 300 miles at most per processing facility just to keep down costs and carbon,” she says. “We're trying to do better for the Earth.”

Addressing Colorado regulations, Fontaine-Billings offers some straightforward advice: “Just always make sure you have your licenses and everything registered on time through the state. That’s really all that I could say to other people is make sure that you’re abiding by the rules because there’s no reason to mess up a good thing.”