When Kansas launched its industrial hemp program in 2019, Aaron and Richard Baldwin recognized the crop’s potential to diversify their fourth-generation family farm. While other growers jumped into the state’s new market with an eagerness to tap into the cannabidiol (CBD) craze, the brothers saw an even bigger opportunity growing hemp for fiber and grain.

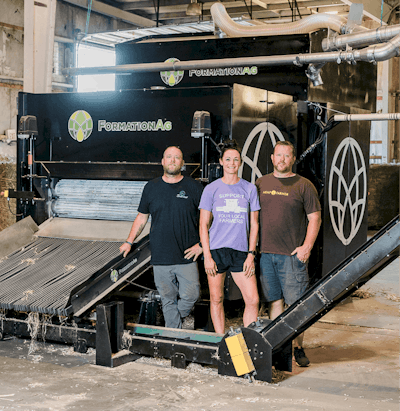

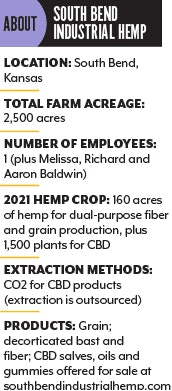

Joined by Aaron’s wife—crop researcher Melissa Nelson-Baldwin—they launched South Bend Industrial Hemp (SBIH) in 2019 to produce hemp for all three uses (CBD, fiber, and grain) alongside crops like corn, soybeans, wheat and milo. By combining data-driven research with generations of farming experience, the Baldwins set out to prove they could produce industrial hemp using traditional agriculture practices.

“At first, [everybody] thought CBD was going to be huge, and there was a good return on acres at first, but we knew that wasn’t going to sustain itself for long,” Aaron says. “We started growing fiber and grain [in addition to CBD] because we knew that was going to be successful in the long run. Three years ago, nobody was really talking about fiber or grain, so we were trying to set ourselves up to be ready when this exploded—and it exploded faster than anybody thought it would.”

Room to Grow

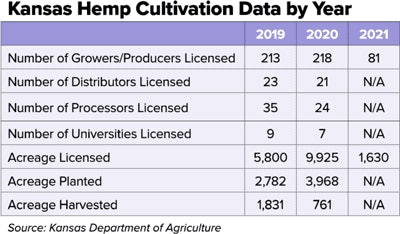

In the state’s CBD-dominant market, floral and biomass material accounted for 90% of hemp production in 2019 and 95% in 2020, according to data from the Kansas Department of Agriculture (KDA). “Compared to floral production of hemp, the hemp grain and fiber production markets remain relatively untapped,” says Braden Hoch, industrial hemp supervisor at the KDA.

For fiber- and grain-focused farmers like the Baldwins, this untapped market presents a huge opportunity—along with plenty of challenges.

SBIH was one of 213 producers licensed to grow hemp in 2019, as part of the state’s pilot hemp program under the Agricultural Act of 2014 (2014 Farm Bill). That year, the KDA licensed 5,800 acres for hemp production—but fewer than 3,000 were planted and about 1,800 were harvested. (See more data from past growing seasons in the table below.)

This year, Kansas only licensed 1,630 acres. While the state adopted a new hemp program pursuant to the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 (2018 Farm Bill) and shifted its licensing regulations—which now only require one individual to be licensed at an operation, instead of licensing every individual involved—the drop in licensed acreage echoes a larger trend as nationwide hemp acreage has started to decline, Hoch says.

As this drop continues across the country, Hoch says these statistics speak to the obstacles that growers encounter with hemp. “It’s still too early to know how successful hemp production will be in the state. Even though we’ve had two seasons of production here, producers are still attempting to determine how to best grow hemp and if it’s feasible to include in their rotation,” he says.

Despite the challenges and nationwide drop in hemp production, at SBIH, the Baldwins have doubled the acreage dedicated to hemp fiber and grain, from 80 acres in 2019 to 160 this year. By learning from their mistakes to fine-tune their operation, they’re applying their experience to not only expand their own business, but also help other growers overcome the challenges inherent to hemp.

Dual-Cropportunity

Based on decades of farming experience, the Baldwins saw plenty of similarities between hemp and the other grain crops grown on their 2,500-acre farm near Great Bend. As with many of these traditional crops, they started growing hemp as a dual-crop—that is, harvesting both fiber and grain from the same plant. (Editor’s note: For more on dual-purpose hemp production, see the latest “From the Field” column.)

“We dual-crop everything else,” Melissa says. “After you harvest the wheat, most farmers bale the remaining straw. You can cut the heads off milo and then graze cattle on the stalks, and people do the same with cornstalks. You need to maximize your acres [by adding] another form of income, and we saw hemp as no different.”

The challenge was figuring out just how to grow hemp alongside other crops. The first year, they tried incorporating hemp into their fields by double-cropping, which is “getting two crops on the same field in the same year,” Melissa says. It was a low-risk experiment, she explains, “because the ground was going to go fallow anyway, and we were able to capitalize off the wheat that was already there.”

After harvesting dryland wheat that July, the Baldwins immediately planted hemp fiber in the same field, covering 80 acres. But by then, “it was too late and too hot,” Richard says. The fiber plants didn’t grow as tall as the Baldwins hoped, and to top it off, a webworm infestation decimated the crop. So, as farmers do, they adjusted their approach.

Now, they plant hemp seeds around mid-April, before sowing beans and corn, when spring rains and cooler temps give hemp “a better chance of surviving,” Richard says. Around mid-May, they also transplant 1,500 CBD clones, which are divided between a greenhouse and a small outdoor grow.

Hemp not only fits into their planting schedule, but also leverages the same equipment they use for conventional crops. “Our focus for fiber and grain is to only use equipment we’re already utilizing on our farm, down to the seed plates in our planter,” Melissa says. “We want to show farmers that they can put hemp in their farming rotation [without any] specialty equipment.”

For example, they use the same 30-inch planter that they use for other row crops and run it through the field twice to achieve 15-inch spacing. They harvest hemp grain with the same combine they use to harvest wheat and soybeans. Then, they swath (cut and place in rows) the remaining plant material and allow it to ret (sit in the field to break down) while they harvest corn and beans, before coming back to bale the fiber.

“At the end of the day, it’s a plant, so we stuck with our core strengths and knowledge as farmers,” Aaron says. “We tried to keep it simple, and I think that’s a big part of our success.”

The Ability to Pivot

As with other crops on the farm, the Baldwins are constantly experimenting with new varieties and growing methods to maximize their yields.

For example, after the 80 acres they planted on dryland in 2019 failed, in addition to changing the planting schedule, the Baldwins switched to different genetics and moved their planting location to land with center-pivot irrigation, where they have more moisture control.

This year, they planted several varieties to compare how different genetics perform with and without irrigation. They planted 120 acres of hemp on irrigated land and 40 acres on dryland.

“On part of our dryland this year, we used a genetic that we had success with on the irrigated [field last year],” Richard says. “We also added a couple genetics to different [corners] of that dryland to find out which ones work in which location.”

Leveraging her crop research experience (which she still conducts from her farm for clients around the world, studying crops they grow on the farm along with potatoes, cucumbers and more), Melissa closely evaluates the results of these trials so the team can keep improving. “One of the reasons we’ve been able to make such productive adjustments year-to-year is because we analyze our data to make educated decisions,” she says.

The team collects data on height, nutrient requirements, leaf tissue samples, and yield, especially the hurd and bast breakdown for fiber varieties. With this data, combined with the Baldwin brothers’ problem-solving farmer mentality, they’re tweaking the operation as they grow. Melissa says: “2019 was a great learning year—not so [great] in terms of production, but in terms of [learning] what not to do. When 2020 rolled around, we learned from those mistakes, and we had a beautiful crop.”

But the Baldwins soon learned that more challenges awaited in this market beyond just growing hemp.

Fixing the Processing Bottleneck

In the spring of 2020, the Baldwins lined up a processor to buy their fiber bales. “We all high-fived and cheered, like, ‘Yes! We’re doing it,’” Melissa says. But when she called the buyer a month before harvest to arrange the final details, she discovered that the processor had lost its funding and shuttered—leaving SBIH stuck with the bales.

“It was such a hard day,” Melissa says. “That’s the hemp industry: You move forward, and you move back.”

But the Baldwins weren’t the only ones getting stuck in the hemp supply chain. Many of the other farmers they talked to were facing the same obstacles as potential processors dropped out and left them hanging. Instead of just looking for another way around the bottleneck, the Baldwins decided to fix it themselves.

“The more people we talked to, we [knew there were] growers that want to grow and manufacturers that want to put in hemp lines, but there was nothing to connect those two pieces,” Melissa says. “So, we started crunching the numbers and [decided to] pursue our own processing facility.”

Around August of 2020, the Baldwins started looking at decortication equipment for the new facility and settled on a long-stranded fiber processing machine from Formation Ag in Colorado. After boot-strapping their entire hemp operation to that point, they began to pursue funding for the machinery—encountering a quick “no” from their bank, which holds the money from their CBD sales. Fortunately, the Formation Ag team helped connect SBIH to a venture capital firm to secure the investment they needed.

The Baldwins purchased an existing building about 5 miles from their farm—conveniently located near an airport, freight and rail transport, with plenty of room to grow. The decorticator arrived in early June of 2021, Aaron says, marking the official opening of their processing facility, which is the first fiber processing facility in the state, according to the Kansas Office of the State Fire Marshal. (The fire marshal oversees processing in the state.)

Scaling Fiber Production

At the SBIH Processing facility, round bales of hemp are fed into the decorticator, which unrolls them into mats. Then, the hemp travels through a series of rollers that essentially break the bast, or outer woody fibers of the plant, away from the inner woody core, known as hurd. Each product heads down a separate conveyor belt for cleaning; then the fiber is degummed, while the hurd is sized and sorted to meet manufacturing specs for various market uses.

“If you can dream it, [hemp] is headed there,” Melissa says. “Everybody talks about textiles, but that’s just scratching the surface. Hemp wood, bioplastics, erosion control, animal bedding, paper mills—you would be amazed at people’s plans to use hemp. People are using fiber for insulation because of the cellulose content, and [using hemp in construction to make] hempcrete. The potential of what this plant can do is really exciting.”

Melissa adds that SBIH Processing has buyers lined up across various industries for the company’s processed products.

The facility is currently processing the bales that SBIH produced last year, which “store nicely, just like any kind of hay,” Aaron says. “Hopefully, we can have it [processed by the time] the new crop comes in. Between those and the acres we have growing now, it will be enough to keep this facility full till next year.”

SBIH recently hired its first employee to run the processing facility, and Melissa says they expect to add more staff within the next year.

To fully capitalize on the decorticator capacity of 1.8 tons per hour, however, they had to look beyond their own fields to find a scalable supply.

Helping Farmers Grow

Early in SBIH’s hemp journey, Melissa began documenting the operation’s highs and lows on social media, “because people were curious about what we were doing,” she says. As their online following grew, this curiosity shifted from skepticism to intrigue.

“In 2019, we had a lot of farmers watching us, but it was like, ‘What are those guys doing? They’re crazy,’” she says. “And then 2020 rolled around and they’re like, ‘Wow, they’re still doing it.’ By the end of 2020, we had people [telling us], ‘If we had someplace to sell this, we would put it on our farm.’”

After talking to plenty of farmers in the area who expressed an interest in growing hemp, Melissa knew they could rally enough support to supply their processing facility. So, in January of 2021, she posted an announcement for a hemp growers’ meeting, inviting other farmers to come and learn how to work hemp into their crop rotations.

“We sat down and helped them compile budgets, and we basically gave them a blueprint to follow,” she says. “We tell them exactly how we want them to plant it and harvest it, because we want them to be successful.”

About a dozen farmers teamed up with SBIH to grow 1,000 acres of hemp for fiber this year (and many of them are dual-cropping to produce grain, as well). Most of these farms are located within 45 miles of Great Bend, except for one grower in Oklahoma and a few in Nebraska.

“We want to help [other growers] be successful, so then in two or three years when our processing facility needs 10,000 acres, we can bring them along with us,” Melissa says. “If you don’t have a local supply, then you lose the economic profitability because you’re going to have to import it.”

SBIH sells the hempseed to their partners at a discounted rate, based on genetics the Baldwins have already tested on their farm. (The company sells seeds to farmers who are not formal partners as well.) SBIH also offers its partners contracts to buy their fiber harvest in the fall. Throughout the season, they’re providing advice and even visiting partner farms to help problem-solve issues along the way.

“We’re focused on making sure that those farmers don’t have to go through the hard ships that we went through the first couple of years,” Aaron says. “We give them a jumpstart so they don’t have to figure it out on their own.”

Embracing Hemp’s Potential

Looking ahead, the Baldwins see plenty of growth potential in their partnership model as more growers team up to supply hemp for their fiber processing facility.

“We’re so excited for what we’re building here, as we continue to connect with people who want to grow for us,” Melissa says. “Our dream would be to open another fiber processing facility by the 2022 sea-son and [to eventually] have a network of processing facilities throughout the Midwest.”

This addition to the state’s supply chain could be a boon for the industry—especially considering nearly 60% of all hemp produced nationwide last year still hasn’t been purchased or processed a year after production, according to Hoch. “The future of [fiber and grain] production is going to be dictated by the infrastructure established to support that production,” he says. “As more processing outlets for fiber and grain become available, potentially that would [connect] producers to the market.”

The Baldwins agree that the success of the hemp industry requires connecting the dots of the supply chain. By giving farmers genetics and advice for growing, along with contracts for processing fiber, SBIH hopes to help the Kansas hemp market reach its full potential.

“I really think Kansas could go back to being the top-producing hemp fiber and grain state in the country,” says Richard, referring to pre-prohibition state agriculture reports that ranked Kansas as the top hemp producer by bushel in 1863. “If we can get the marketing and manufacturing of products [aligned] with the demand for fiber and hurd, we could be producing tons and tons of fiber for the world.”