The Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 (the 2018 Farm Bill) reversed a decades-old prohibition on cultivating industrial hemp, allowing a new generation of farmers to plant hemp seeds across the country.

They didn’t waste any time.

Just a year later, in 2019, farmers had planted 285,000 acres of hemp, up from 78,000 in 2018, according to a report from market research firm Brightfield Group. The report predicts that 2.7 million acres will be under cultivation by 2023.

But in addition to launching a potentially lucrative industry for farmers in most states across the nation, the farm bill also introduced an unintended consequence for the criminal justice system. By legalizing the cultivation of hemp, it complicated matters for marijuana prosecutions.

Law Enforcement Conundrum

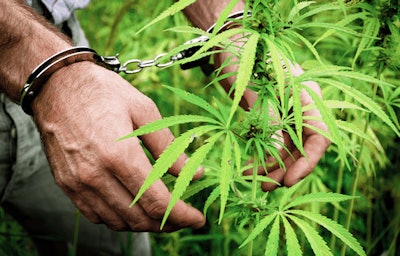

A November police raid of a farm in Wyoming illustrates the conundrum for law enforcement.

The case began when the Wyoming Division of Criminal Investigation received a tip last September, according to Wyoming news outlet WyoFile. The caller said a family in eastern Wyoming was cultivating marijuana. Two months later, agents executed a search warrant upon the farm, operated by Deb Palm-Egle and her son, Josh Egle, and confiscated what they believed was 722 pounds of marijuana.

Upon testing the crop, authorities found that nine out of ten tests showed the plants contained more than 0.3% tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), meaning under federal law, the plants were marijuana.

The family, however, said it wasn’t growing cannabis. The crop was supposed to be hemp.

WyoFile’s reporting on a court filing from July 2020 provides key details. In it, the Egles’ lawyer offered a wealth of evidence showing the family intended to grow hemp.

The evidence included the fact that before the state legalized hemp, the Egles had testified in front of Wyoming legislative committees championing the crop. Evidence also showed text messages from the Egles indicating all previous laboratory tests conducted upon the crop registered less than 0.3% THC.

The question of intent poses a significant challenge for law enforcement. A conviction on the offenses charged requires not just an overt action, but also a culpable mental state.

Importantly, none of the results of the potency tests conducted on the confiscated plants exceeded 0.6% THC. In his filing, the Egles’ lawyer shows that THC concentrations that low are far removed from concentrations found in marijuana for sale in dispensaries across the border in Colorado, where a THC potency around 15% is often the lowest concentration available to consumers. In other words, the Egles’ crop was not marketable as marijuana in a legal market. In addition, the lawyer argued that if the Egles intended to distribute their product on the illicit market in Wyoming (where neither recreational nor medical cannabis is legal), the THC concentration is so low that selling it would invite retaliation from angry customers.

Prosecutors charged the Egles with conspiracy to manufacture, deliver, or possess marijuana; possession with intent to deliver marijuana; possession of marijuana; and planting or cultivating marijuana. If convicted, the family could have faced decades in prison. However, despite the Egles not having a legal hemp producer license in Wyoming, a judge dismissed the case in early August, finding prosecutors lacked probable cause that the duo intended to grow and distribute marijuana, according to WyoFile.

Proving Intent

The question of intent poses a significant challenge for law enforcement, as a conviction on the offenses charged requires not just an overt action, but also a culpable mental state. Criminal intent is an extremely important concept in law.

Some offenses require only an illegal action. For example, speeding will land someone a ticket even if they didn’t realize they were going too fast. Most offenses, however, require a criminal act and a culpable mental state. While the Egles’ product may have been above the THC concentration permitted by the 2018 Farm Bill, a technical violation alone without criminal intent was a difficult case for prosecutors to try. Among other things, the prosecutor would have had to persuade the jury beyond a reasonable doubt that the Egles intended to cultivate illegal cannabis.

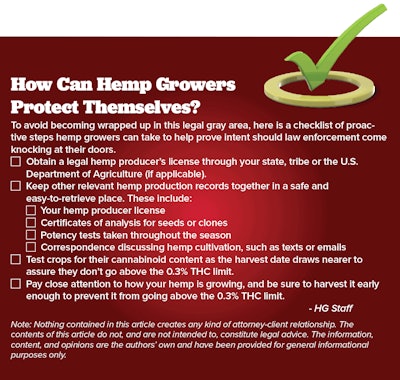

With the passing of the 2018 Farm Bill, a large number of pending marijuana cases will likely be dismissed, or prosecutors will present much less punitive plea deals to the benefit of the defendant, because of the difficulty of trying a marijuana case. This is the unintended consequence of the 2018 Farm Bill—this legal gray area of cultivation of hemp as a defense for a marijuana charge.

The crux of the issue is that hemp and marijuana are the same genus (Cannabis) and species of plant. They are, taxonomically speaking, the same. The only thing that divides them, from the standpoint of the federal government via the 2018 Farm Bill, is the arbitrary determination of 0.3% THC content as the dividing line between the two. If the percentage is 0.3% THC or less, it’s hemp. Otherwise, it’s marijuana.

In many cases, THC content does not begin to flood the plant until the plant reaches maturity. As a result, plants that are confiscated by law enforcement prior to reaching maturity are hemp if they have not yet achieved more than 0.3% THC, even if those growing the plants planned on selling the buds as marijuana.

This complicates cannabis prosecutions.

More Potential Scenarios

A case in Rhode Island was recently brought to our attention that demonstrates a different, but equally complex, law enforcement consequence of the 2018 Farm Bill. In this case, federal agents raided a house and found plant roots, which the agents concluded were to be used to grow marijuana. The raid uncovered other drugs, like cocaine.

The cocaine might be straightforward for prosecutors. But the roots could prove difficult. The reason? As discussed, mere visual analysis of hemp and cannabis plants is not sufficient to determine the difference between them—it requires testing, and plants do not even begin producing measurable THC until they reach certain stages of maturity. Either way, roots—something far removed from a mature cannabis plant—will not contain THC in excess of 0.3%.

In the case of the roots, genetic samples are unlikely to prove anything either. Prosecutors would have to show that the roots are genetically similar to another marijuana plant in a cannabis database, in which case they might have some luck making a case. But the chances the database would have a direct genetic relative of the roots in question are next to nil.

All of this helps expose the serious challenges the 2018 Farm Bill has presented for law enforcement.

If, for example, law enforcement found 5,000 cannabis plants in a basement that were not yet at a stage producing THC in excess of 0.3%, the prosecution would face high hurdles for a marijuana conviction. The prosecution’s strongest tool would revolve around intent. If the grower revealed he was intentionally growing illegal cannabis in his basement through text messages, email, social media, and even personal conversations (with friends or confidential informants), then the prosecution could show intent. It might be enough for a conviction.

Let’s consider another possible scenario: A grower is intentionally cultivating marijuana in her basement. She never revealed this through communications. Law enforcement agents raid her house, confiscate the plants and charge her with various crimes.

She tells them she is growing hemp.

If the plants are not yet mature enough to produce THC above 0.3% at the time of confiscation, the agents technically confiscated hemp.

While not having a legal hemp producer license is a strike against her, it still may not be enough evidence to prove her intent to grow marijuana.

With a crop that is hemp, and no sound evidence that the defendant intended to grow marijuana, gaining conviction now is more difficult for prosecutors than ever.

The development marks yet another step, albeit an accidental one, in this country’s march toward cannabis legalization. The first big step took place in California in 1996 with Proposition 215, which legalized medical cannabis (aka marijuana, or containing above 0.3% THC). Then, in 2014, Colorado became the first state in the nation to permit the sale of adult-use cannabis. Today, 33 states plus the District of Columbia allow some sort of legal cannabis.

The 2018 Farm Bill didn’t explicitly change anything about the legal status of marijuana, but it absolutely made convictions in many cannabis cases more difficult for law enforcement.