Cannabidiol (CBD) was the pot of gold many farmers were chasing.

Hemp-derived CBD was somewhat of a stranger at that time, but the non-psychoactive cannabinoid’s popularity catapulted a multi-billion-dollar market that not only includes tinctures, oils and vapes, but also CBD-infused drinks, topicals and edibles. The overall U.S. CBD market reached $4.2 billion in sales in 2019, according to a report by the Brightfield Group, a resource organization with artificial intelligence-driven consumer insights.

But as U.S. farmers made a rush to meet the hyped demand for CBD, prices plunged. Market saturation resulted in warehouses and barns full of unsold supply throughout the country. In Minnesota, 74.4% of hemp acres planted in 2019 were meant for CBD extraction, while grain-type hemp represented 25.2% and fiber represented 0.4%, according to the Minnesota Department of Agriculture’s (MDA) annual report.

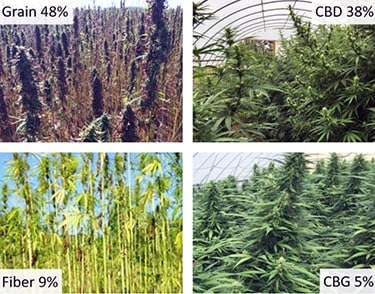

But with price drops in the 2019 CBD market, an alarming amount of biomass went unsold. Even in February 2021, some plant material from two seasons ago has yet to be processed. Responding to that market saturation, Minnesotans shifted their focus to grain hemp, which represented 48% of acres planted in 2020, while CBD dropped to 38% of acres planted, fiber grew to 9% and cannabigerol (CBG) represented 5%, according to that year’s annual report.

RELATED: Interest in Hemp Fiber Rising as Farmers Look to 2021

Jeremy Saueressig, the owner of SporoBio, a farm-to-table hemp company in Hastings, just southeast of Minneapolis, that specializes in farming, consulting, processing and product development, kicked off his first grow in 2019, partnering with a half-dozen farmers to plant more than 100 acres of CBD-type hemp, from which they ended up harvesting about 80 acres because some fields grew hot, he says.

“We probably overproduced,” Saueressig says. “We’re still monetizing the crop from ‘19 now. We’re still actually processing ‘19 crop. It was just unbelievable how much biomass we had from that. I mean, we’ve processed quite a bit of 2020 crop too, but there’s still 2019 around. People still have it, which is crazy.”

Overall, Minnesota’s 4,690 acres planted outdoors in 2020 was a 36.2% decrease from the 7,353 acres planted in 2019. Also, there were 444 licensed growers in 2020—71 fewer than in 2019.

Multiple factors played a role in those decreases, including, but not limited to, crops testing above the legal tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) limit of 0.3%, as well as the market saturation, says Tony Cortilet, the MDA industrial hemp program supervisor.

“A lot of [growers] might not have gotten licensed again in 2020 because they probably got hit pretty hard,” Cortilet says. “And that also probably caused some issues between buyers and sellers, with them going into 2019 with high expectations and promises of, ‘Hey, if you grow this much hemp, bring it to me and I’ll buy it for “X” amount.’ And then those prices couldn’t be honored once the fall came around because of the midsummer price slumps.”

Hemp biomass prices were fetching more than $4 per percentage point of CBD content per pound in July 2019, according to three PanXchange benchmarks—covering Colorado, Kentucky and Oregon. But as the U.S. supply roughly quadrupled from 2018 to 2019, the trading value dipped. By November 2019, after farmers harvested their crops, biomass transacted in the range of $0.80 to $1.40 per percentage point of CBD content per pound, according to PanXchange.

RELATED: November 2019 Hemp Market Update: PanXchange Benchmark Pricing

In other words, if growers had 100 pounds of plant material with 10% CBD content, a processor contract at $1 per percentage point would be worth $1,000—much less than $4,000 at $4 per percentage point.

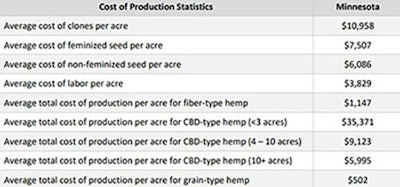

Launching his operation in 2019, Saueressig says the input costs at SporoBio were more than $12,000 an acre, depending heavily on sourcing genetics and obtaining the proper certificates of analysis. The average yield for CBD hemp biomass was 1,039 pounds per acre for Minnesota farmers in 2019, according to MDA. Above the curve, SporoBio’s machine-harvested yield can produce upward of 4,000 pounds per acre, Saueressig says. For hand-bucketed yields, SporoBio expects around 2,000 pounds per acre, he says.

On the lower end—2,000 pounds per acre for hand-bucketed yields—SporoBio would have had in the vicinity of 160,000 pounds of biomass from the roughly 80 acres it harvested in 2019.

If 20 acres grew hot—or tested above the 0.3% allowable THC limit—that was the equivalent to roughly $240,000 in lost input costs for SporoBio in 2019, as well as the equivalent of more than $400,000 in lost trading value, based on a benchmark of $1 per percentage point of CBD content. (Although, SporoBio does its own processing, including extraction, so biomass trading value isn’t as relevant as it would be if Saueressig was trying to sell his raw materials.)

“Overall, I thought it was a great, great learning year,” Saueressig says. “It sucked for the guys that went hot, and we kind of coordinated it where we formed a six-person co-op because we didn’t know who was going to fail or who would grow big, and that’s how we’re dividing up all the sales now, is just equally among the acres of the growers. So, nobody lost their shirt yet.”

In 2020, Saueressig says SporoBio just about halved its input costs at roughly $6,000 an acre. His goal in 2021 is to further reduce his input costs to $2,000 an acre, leaving him a much greater margin for profits. And, of course, preventing crops from growing hot helps too.

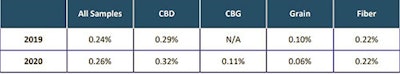

In 2020, the MDA collected 762 samples from hemp growers. Of those, 77 tested above the 0.3% THC threshold, which is a 10% failure rate. In 2019, the failure rate was 13%. That downward trend is promising, Cortilet says, but it’s also a result of more farmers shifting their business models to incorporate grain, fiber and CBG.

In 2020, hemp varieties grown for grain tested at 0.06% THC, on average, in Minnesota, while CBG tested at 0.11% THC and fiber tested at 0.22% THC, according to the MDA annual report. Meanwhile, hemp grown for CBD tested at 0.32% THC on average—a 0.03% increase from 2019. In other words, farmers have a much better rate of remaining compliant with grain, fiber and CBG.

“It’s unfortunate if you’re in that [10%] failure rate,” says Cortilet, whose department is in charge of the state-administered tests.

“We need remediation at some level,” he says. “This is going to kill the industry, you know, forcing a person, who has no intent of growing marijuana, as defined, and they buy their seed thinking everything’s great. Then they put it in the ground, and something happens beyond their control. Why should they be penalized financially like that? We don’t do that for any other crop.”

Before SporoBio launched its hemp operation in 2019, Saueressig says he partnered with Grain Handler, a Minnesota-based manufacturer of equipment used in the post-harvest processing of multiple types of grain. The company also built SporoBio post-harvest equipment for drying hemp, which Saueressig says he foresaw as a bottleneck of the industry.

As of early March 2021, Saueressig was focused on upgrading his processing capabilities, which not only include drying, but also encompass grinding, extraction and distillation, he says. A year earlier, he hired a lead chemist—one of the top-paying jobs in the industry—to run that side of his operation.

“That was the best investment we made yet, because he can get us there a lot faster, you know, he just understands chemistry and that’s what extraction is, a hundred percent of it,” Saueressig says. “I don’t second guess that hire any day of the week.”

The CBD distillate market is leveling off in Minnesota, Saueressig says, while CBD isolate—a crystalline solid or powder comprised of near pure CBD—is what’s in demand, so that’s where SporoBio is shifting its focus.

While Saueressig appears to be all in with his CBD operation at SporoBio, investing roughly a couple million dollars in his processing capabilities, he says, the barrier of entry into the CBD hemp industry is not for everybody. For many farmers, gambling $10,000 of input costs for an acre of hemp that may or may not grow hot, is not in the bag.

In 2020, Minnesota farmers planted 56% percent of the projected 8,400 acres that were licensed, Cortilet says.

“They might say, ‘I’m going to do 1,000 acres,’” Cortilet says. “And then they realize how much Cherry Wine costs per seed, or clone, and then they go, ‘Oh, I can’t afford that. I’m going to cut that into a quarter, and that’s what I’m actually going to plant.’”

While there was that rush to plant CBD hemp in 2019, Minnesotans focused primarily on grain-type hemp during the first three years of the state’s pilot program, with 94.7% of crops dedicated to grain hemp in 2016, 99.3% in 2017 and 87.9% in 2018. Then came the CBD hype in 2019, when grain hemp dropped to 25.2% in the state.

But with market saturation and the costs associated with CBD hemp, grain took back over in 2020 with 48% of farmers shifting their focus to that hemp type. The average total cost of production per acre for CBD hemp, for 10-plus acres grown, was $5,995 for Minnesotans in 2019, while the average total cost of production per acre for grain hemp was $502, according to MDA.

“We had a re-uptick in seed (grain-type hemp), which was promising,” Cortilet says. “I think you’re going to see that continue. So, this market saturation [for CBD hemp] will most likely correct itself. I’m assuming in every state across the U.S. more people will be producing seed and finding a market. It’s just, seed is so easy, right?”

In a state like Minnesota, where agriculture is row-crop centric, there’s a foundation of cleaning seed for sale, Cortilet says. In other words, there are plenty of facilities for a farmer to take his or her crop to get it cleaned, dried and have it stored. The main challenge right now is getting more facilities that are hemp-specific, Cortilet says.

“We have quite a bit of diversity up here compared to, like, Iowa, which is primarily corn and soybeans,” he says. “We have a lot of small greens We have a lot of sunflower plants that, you know, they’ll take hemp in. The problem is they have to have enough of it at that particular time to clean up their assemply line from one commodity to allow hemp to come in. They can’t mix them, which means they can’t just get a couple of trucks from farm ‘X’ over here, which was what was happening early on. There just wasn’t enough hemp seed for them to clean. So, it’s really that those [acres planted] are impacted by, ‘Where do I bring it to?’”

Once more facilities geared toward grain hemp are built, then more farmers would likely switch their operations toward that grow, especially if market saturation for CBD hemp continues with volatility, Cortilet says.

But volatility in agriculture is not confined to hemp. Various circumstances, such as weather events wiping out an entire harvest, can affect the struggles or successes associated with other crops. Proper storage is key to taking advantage of the market, Cortilet says. When it comes to storing tens of thousands of pounds, or more, of CBD hemp biomass, that’s not always convenient.

However, grain and fiber cultivation practices are more on the same wavelength of traditional farming, whether commercial or organic, where farmers are always storing something, Cortilet says.

“You’re built for that,” he says. “You’re going to preserve your crop until the right time to sell, and the right time always isn’t at harvest. I’m not sure if the cannabinoid market is there, but I think it’ll get there. I’m not an expert, but I can say this: a lot of the folks getting into that area of hemp production, I would not say they’re all what you would typically call a traditional farmer, and that’s kind of cool.