This is Part II of a two-part series on taking your company public. Part I of the series—“Going Public: Are You Ready?” (including a 7-point checklist)—ran in Cannabis Business Times’ July issue.

So, you think you’re ready to go public. Now what?

To become a publicly traded company in the U.S. or Canada, there are basically two options: an IPO (initial public offering) or an RTO (reverse takeover—or “reverse merger” in the U.S.).

In an IPO, companies sell shares to the public via a stockbroker. In an RTO, a business buys enough shares to control a publicly traded “shell,” then exchanges shares in its private company for shares in that shell. The process allows the business to go public without having to endure the same scrutiny from regulators and investors.

The path you choose will depend on several factors. The first and most important is corporate domicile. Does your primary business take place in Canada, where cannabis is legal? If so, an IPO on the Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX) or even the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) or Nasdaq may be the most logical, and potentially the most lucrative, course. Because banks in Canada recognize cannabis companies as legitimate businesses, the listing process on primary exchanges, such as the NYSE or TSX, is cleaner and easier. (Many Canadian cannabis companies, such as Aurora Cannabis and Canopy Growth, have shares listed on both Canadian and U.S. exchanges.)

But if your business is based in the U.S., where adult-use cannabis is legal in only 11 states and Washington, D.C., and remains banned at the federal level, one of the only options available is an RTO on the Canadian Securities Exchange (CSE). A handful of multistate U.S. cannabis operators have already taken this step in the hopes of eventually uplisting to a larger exchange once the laws change.

“We’re seeing more U.S. companies start the process of preparing for a go-public transaction but deferring an actual filing, as they’re hoping for more clarity on the direction of the U.S. regulatory environment and what impact any changes may have on the willingness of the U.S. exchanges to list U.S. cannabis operators,” Scott Hammon, COO of the MGO | ELLO National Cannabis Alliance, tells Cannabis Business Times.

Regardless of whether your company is U.S.- or Canada-based, the decision between an IPO or an RTO will always come down to the nature of the transaction (a rollup of multiple entities versus a single company), the availability of “reasonably priced” shell companies, timing and price, according to Hammon. IPOs are typically more expensive to execute and take longer, but many bankers believe an IPO will price higher, Hammon says.

In this article—Part II of a two-part series—cannabis industry experts share the pros and cons of IPOs and RTOs and offer advice you should consider before making a final decision.

Understanding U.S. and Canadian Exchanges

Before you choose between an IPO or RTO, you must pick an exchange. In Canada, almost all Canadian cannabis stocks trade on one of three exchanges: the TSX, the CSE or the TSX Venture Exchange (TSXV).

CSE: Originally operated as the Canadian Trading and Quotation System Inc., the CSE has lower listing and reporting requirements than the TSX and the TSXV. The Canadian Securities Exchange has become the most common exchange for Canadian cannabis companies and a haven for many U.S. companies seeking access to capital. The CSE is the only stock exchange in either the U.S. or Canada that will list cannabis companies with U.S. operations. Companies currently listed on the CSE include Acreage Holdings, C21 Investments and Vireo Health.

TSXV: In Canada, the TSXV is like the Nasdaq Capital Market in the U.S. or over-the-counter (OTC) markets. The exchange serves as a public venture capital marketplace for emerging companies (small cap). The TSXV lists 40 cannabis companies on the exchange as of May 31, including Delta9 and ABcann Global.

Neither the TSX nor the TSXV will list companies involved in the cannabis industry in countries where the research, cultivation or sale of cannabis products is illegal.

In the U.S., meanwhile, there are two major exchanges on which cannabis companies should set their sights—the NYSE and Nasdaq.

NYSE: This exchange dates to 1792 and is home to many of the world’s “blue chip” companies, whose stocks tend to be older and more stable.

Nasdaq: The Nasdaq is younger (circa 1971) than the NYSE and lists a broader spectrum of companies. Many corporations listed on the Nasdaq have market capitalizations of $200 million or less.

Neither the NYSE nor Nasdaq allow companies that deal with marijuana in the U.S. to list their shares. That includes Canadian companies with operations in the U.S. But both exchanges will list Canadian cannabis businesses that exclusively operate in Canada because cannabis is legal in their home country. At press time, 11 cannabis stocks call NYSE or Nasdaq home: Innovative Industrial Properties, Cronos Group, Canopy Growth, Tilray, Aurora Cannabis, Aphria, HEXO, Village Farms International, CannTrust Holdings, Greenlane Holdings and OrganiGram Holdings. Only three (Innovative Industrial Properties, Greenlane and Tilray) debuted via an IPO. The rest uplisted from smaller exchanges, meaning they moved into a bigger exchange after meeting that exchange’s requirements.

Going Public Via RTO

Once considered a “back-door” entry to a public listing, the RTO has become a viable, and often preferred, option to the IPO. Between 65 percent and 70 percent of Canadian companies make their public debut through RTOs, according to GoPublicInCanada.com, an online marketing initiative by ITB Solutions Inc.

The biggest advantage of an RTO, according to experts interviewed for this article, is timing. A reverse takeover typically takes three to six months to complete. That includes identifying a shell company, beginning a due-diligence process and determining the stock ratio and range. In sharp contrast, IPOs can drag on for more than a year before their trading debut. This is because underwriters need to pore over a private company’s financials, liabilities and assets to intelligently price the stock, and because federal regulators must examine every document to determine whether the firm complies with securities laws and regulations. With an RTO, the due-diligence and review process is simpler and can be completed in less time. While companies still need to prepare an “information circular” for an RTO, the shell company with which they strike a deal already has listing status and is presumably operating within the guidelines of Canadian securities. As Hammon notes in the whitepaper, “Going Public in Canada: A Roadmap for Cannabis Industry IPOs and RTOs,” that RTO “information circular” may not need to be filed with or reviewed by securities regulators, a huge time-saver.

Another advantage, according to experts, is price. With an IPO, an underwriter’s commission can be as high as 7 percent of the offering, according to Hammon. With an RTO, however, you may not need to engage an underwriter at all.

Darrell Peterson, a partner at Bennett Jones LLP, noted in his report, “Cannabis: Initial Public Offering Checklist,” that in addition to those underwriter fees, other expenses in completing an IPO in Canada include auditor fees, filing fees (which are paid to Canadian securities regulators when filing a prospectus in all provinces), legal fees, listing fees (which are paid to the applicable exchange), marketing costs, printing costs and translation costs (if any part of the offering is made in Québec, where French is the primary language).

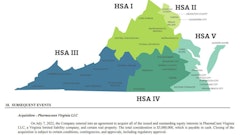

For this and other reasons, the RTO has become a trusted ally of cannabis companies, especially multistate U.S. operators. A few notable U.S.-to-Canada RTOs:

- MedMen, a Los Angeles-based cannabis company with storefronts in California, New York, Arizona, Illinois and Florida (and forthcoming in Massachusetts), and a greenhouse facility in Nevada, began trading on the Canadian Securities Exchange after completing an RTO with Vancouver-based Ladera Ventures Corp.

- Chicago-based Green Thumb Industries debuted on the CSE after the company’s owner VCP23 LLC completed an RTO of Vancouver’s Bayswater Uranium Corp.

- And California retailer Harborside reverse-merged with Toronto-based Lineage Grow Company Ltd., which had spent months acquiring California growers. The result of that deal was a vertically integrated cannabis company that will be known as Harborside Inc.

As these companies can attest, the key to executing a successful RTO is finding the right shell, because not all shells are created equal. Some have cash or other assets, or debt. Some are dormant operational companies with no assets, or firms established as shells for the sole purpose of attracting interest in an RTO transaction. (In Canada, capital pool companies (CPCs) have experienced directors and capital but no commercial operations.)

In Harborside’s case, Lineage came to the table not only with listing status on the CSE but three stores and two grow operations—one indoor and one outdoor.

“It rounded out our vertically integrated portfolio of assets and supported our strategic growth plans, versus just offering an empty shell,” says Andrew Berman, CEO of FLRish, doing business as Harborside.

As Berman found, the RTO provided another distinct advantage. The deal with Lineage helped Harborside raise capital without diluting its ownership.

“We came out controlling our own destiny,” Berman says of the Harborside RTO. “FLRish will own most of the outstanding shares, control five of the seven board seats, and have an executive team of me, Chief Operating Officer Menna Tesfatsion and General Counsel Jack Nichols.”

Going Public Via IPO

Prior to the rise in popularity of reverse mergers, most companies went public through the IPO process.

As Peterson noted in his report on the subject, an IPO offers many advantages, such as liquidity for existing shareholders, immediate equity capital, opportunities for future financing, and the ability to complete mergers and acquisitions using the issuer’s publicly traded shares as “acquisition currency” and by raising cash through the sale of additional equity. The disadvantages include loss of control, restrictions on management decision-making and, of course, the time and cost commitment.

But perhaps the biggest reason to consider an IPO is prestige.

Scott Greiper, president of Viridian Capital Advisors, a financial and strategic advisory firm dedicated to the legal medicinal and adult-use cannabis market, says that IPOs were historically reserved for higher-quality, higher-revenue-generating companies, while RTOs have been used as a low-cost tool for less-proven, less-sophisticated companies.

For many years, institutional investors “wouldn’t touch” an RTO, Greiper says. “The thinking was, if the company was good enough, they would’ve gone public via an IPO,” he says. “That’s not to say there’s anything inherently negative with an RTO. You’re essentially acquiring a public shell. But to some investors IPOs have a better perception.”

While it’s true that IPOs can take longer to complete and can be more expensive, the RTO process is actually taking longer than usual these days because there are more companies looking for shells, Greiper says.

Whether you opt for an IPO or RTO, Greiper says investors want to see an experienced management team with a demonstrable track record of good performance.