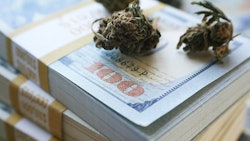

Editor's Note: This article originally published on Cannabis Business Times' website with the headline, "Debt Markets and Cannabis Firms Find Each Other."

We are, all of us, swimming in debt. If you don’t owe anyone a penny then you’re not contributing to the International Monetary Fund’s estimate of $60 trillion of household debt.

Still, as a citizen of a sovereign nation or even a resident of a small town with a water tower to pay off, you’re on the hook for some of the $120 trillion of public-sector debt trading on the world’s bond markets. The IMF calculates that there’s roughly the same total of debt obligations issued by non-bank corporations globally. For comparison’s sake, the total market cap for all the world’s stocks is only about $93.7 trillion, according to the World Bank.

In other words, debt isn’t just big business. It’s the biggest business.

There are reasons why debt financing has become so much more attractive to issuers than equity. Some involve drivers internal to the firm—the founders’ desire to maintain control, for example. Some drivers are external—both regulatory and economic.

“[A] quirk of the U.S. tax code favors companies with capital structures that lean toward debt rather than equity,” according to American Estate & Trust. “Interest payments are tax-deductible; dividend payments are not.”

While Internal Revenue Code Section 280E, as applied today, prohibits cannabis businesses from deducting that interest along with many other standard expenses, it all hinges on cannabis’s classification as a Schedule-I drug and the murky legal definition of “trafficking,” according to the Congressional Research Service. So it was just a matter of time before the cannabis industry switched from equity to debt as an emergent funding source.

“Debt financings [in the cannabis industry] reached their highest percentage level since we began tracking these stats, reaching 44% of total dollars raised in 2021, up from 38% in 2020,” wrote Viridian Capital Advisors President Scott Greiper and SLB Capital Advisors Principal David Rosenberg in Cannabis Business Times in March. “Debt capital raised increased to $5.62 billion in 2021 from $1.65 billion in 2020. Seven of the largest 10 capital raises of the year were debt transactions.”

Part of that has to do with the industry-specific dynamics of cannabis. For the past year, stock prices among the peer group’s leaders have been declining, weakening their appetite for raising more capital on equity markets. It is telling that Canopy Growth Corp., which has the biggest debt issuance in the industry year-to-date with a $750-million bond, has seen its stock price plunge from $45.40 in February 2021 to a recent close of $5.79 as of press time.

Cannabis’s Debt Market

When an industry is in its infancy, it might attract the kind of risk takers who prefer an equity stake in the financial markets. Once it is established, it can target the lower end of the capital stack.

Investors who extend debt financing care little for the potential upside of ownership and instead seek a steady return come boom and bust. Apparently, cannabis has turned that corner.

“More and more companies are mature enough to deliver the cash flow,” which bond buyers find attractive, according to Greiper. “They also have real estate, equipment and other assets to put up as collateral.”

Still, not every institution that would consider lending to growers can actually do so.

At issue is the legal gray area in which cannabis cultivation takes place: protected by state law, yet still felonious under federal law. While Washington has been loath to crack down on operations, banks that are insured and regulated by federal agencies avoid underwriting the industry’s bonds just as they avoid offering standard business loans. Legislation to enable banking access has passed the House of Representatives and is stalled in the Senate. Even such borderline-usurious choices as factoring or merchant cash advances are difficult to arrange, although Fundera lists a few sources.

The overwhelming source of debt financing, by default, is privately placed bonds. As the name implies, these are not exchange-traded, at least not upon issuance; a secondary market might or might not emerge.

The Securities Act of 1933 sets the rules for equity and debt instruments in the U.S. with the presumption that they will be traded on exchanges, in part by non-experts who are unsophisticated when it comes to financial matters. To start with, these instruments must be registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission, which involves a lot of money and a proportionate amount of time filling out paperwork. There are permissible ways, however, to issue shares or bonds without registration, as long as the buyers are mostly if not entirely what are considered accredited investors. Anybody who knows precisely which accredited investors are investing in any specific private placement isn’t telling. But these are almost certainly not banks, nor are they likely to be funds that need to adhere to a fixed charter.

“I expect most of the money [funding cannabis private placements] comes from non-regulated businesses and wealthy individuals,” according to Franklin G. Snyder, a Texas A&M University law professor who teaches a course in cannabis business law.

These exemptions lower the reporting requirements and thus the time and expense for tapping capital markets. The governing rule for private placements under the 1933 Act is Regulation D.

The Details of Private Placement

A prospective issue—say, a licensed cultivation business or a multistate retailer—would electronically file a short Form D upon listing their securities. It is not a formal prospectus and does not prompt any financial disclosures. Even so, a brief prospectus—called a private placement memorandum (PPM) in the trade—is usually attached.

A PPM should include:

- offering terms,

- company description,

- management and principal shareholder biographies,

- use of proceeds,

- collateral (if any),

- description of securities and

- risk factors.

Reg D’s Rule 504 permits microcaps to solicit investments.

Rule 506(b) and Rule 506(c), meanwhile, apply to established entities choosing not to trade on exchanges.

In addition to the federal rules, most states have what are called “blue sky” laws that vary from one state to the next, although the standard template is the Uniform Securities Act.

Reg D’s Rule 144A provides a safe harbor from registration requirements for private resales, providing liquidity to the secondary market. While this is not explicitly geared toward debt as opposed to equity instruments, debt accounts for the bulk of the volume. 144A securities trade on the Nasdaq Private Market Solutions platform.

If collateral is pledged as part of a listing, the PPM needs to mention that as well. In the cannabis space, real estate has the most tangible and most easily monetized value. That poses another important consideration when listing securities: Cannabis is the highest-margin crop on the market but, should a business face foreclosure, the debtholders are likely to have little interest or expertise in growing those plants. They might require the issuers to have the property appraised twice—both as an ongoing operation and for its highest and best non-cannabis use.

And collateral will almost always be pledged because cannabis is, despite its enviable cash flows, a risky business just from its regulatory environment. Even Canadian insolvency trustees have little legal leeway to monetize the inventory. According to Snyder, U.S. bankruptcy courts can’t touch it. He notes that companies can work around that by separating the product and the real estate in separate legal entities.

Even with that collateral, though, there is a risk premium to be paid. While debt might be less expensive to raise and maintain than equity, cannabis debt is not cheap compared to blue-chip debt.

“No one’s looking at these [cannabis company] bonds and confusing them with General Electric’s,” Snyder says.

The lowest interest rate that can be hoped for at the moment can be inferred from the 7% note that the Pelorus Equity Group cannabis real estate investment trust (REIT) issued last year—when interest rates were measurably lower. Pelorus is using the $42.2-million raised to lend out—presumably at higher rates—to its portfolio companies.

Cannabis companies generally do not get investment-grade ratings from the bond raters at Standard & Poor’s or Moody’s (Viridian offers a rating scale specific to the industry), and investors generally don’t commit to private placements for any yield under 10% at an absolute minimum. Stem Holdings’ recent raise for a modest $500,000 offered a 10% coupon, according to Viridian.