In February 2022, yet another California cannabis delivery service hit the rolling hills and valleys of the largest cannabis market in the world. In one of the more competitive sectors of the licensed retail landscape, this one came with a little extra celebrity panache.

Cheech & Chong’s Takeout was open for business, promising deliveries in under an hour. Early press materials hinted that brand namesakes Cheech Marin and Tommy Chong themselves may even hand- deliver the goods at customers’ doors. To anyone familiar with the iconic comedy duo, this perhaps was not a total surprise. Both Marin and Chong enjoy being involved with the business, the cultural dynamics, the rich and complicated tapestry that is a life spent loving cannabis.

As Chong jokes via Zoom from his home in Los Angeles: “We’ve been in the marijuana business longer than marijuana’s been around.”

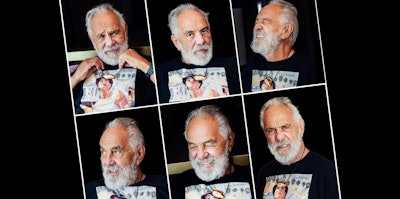

At 84, Chong presents as a wiser, more authoritative version of his late-1970s persona, his most iconic era. He still speaks with the slackerish stoner drawl that many now associate with pot culture, but he does so while describing decades of slow legislative reform and private business development. He is an elder statesman of this strange new territory, one of the very few leaders who can lay claim to a true lifetime of service in this plant’s honor. He was running circles around the American cannabis world well before some of its current CEOs were born.

Cheech & Chong’s Takeout, by all accounts, has been a hit. It was a logical step forward for the ambassadors of cannabis. Chong points to the rise of delivery services during the pandemic as not only an economic opportunity, but also a trend that harks back to his youth in the outskirts of Calgary in the 1940s and 1950s. Back then, household goods were bought and sold via catalog: Delivery brought the store to the customer rather than the other way around. The goal for Chong and his team was to create a more personal experience for the modern cannabis customer. For anyone with even a passing knowledge of the Cheech and Chong filmography, how could they say no?

“Our movies were basically all about either receiving or delivering product, you know?” Chong says. “Only this time we don’t have to worry about being arrested.”

And yet, the state of cannabis delivery today underscores one of the many shortcomings of the legal industry.

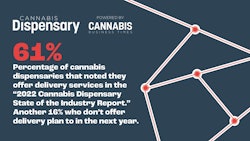

In California, some 61% of cities and counties prohibit cannabis retail operations, according to the state Department of Cannabis Control. This is a hyperlocal geopolitical hurdle for the early years of legal cannabis. If local governments don’t opt in, the market remains stymied. The rub here is that delivery services are indeed allowed to cross county lines and service even those areas under a business ban. Delivery is the only way to connect the booming industry to its customers in most parts of the state.

So, Cheech and Chong wanted to circumvent the more sluggish aspects of the cannabis space and just get right down to it: This plant is a powerful force of good, and it’s high time it got into the hands of people who need it most.

“What we’re dealing with is medicine,” Chong says. “And we’re getting our medicine to the sick people as fast as we can.”

Perhaps this has been the plan all along. If there’s one thing that has propelled Chong’s remarkable life and career, it’s access to cannabis.

***

Chong was born in 1938 and raised as the younger of two brothers in Calgary, Alberta. His mother was Scotch-Irish, and his father was a Chinese immigrant. As a boy, Chong spent most of his time with Ukrainian relatives brought into the Chong family tree by way of his aunt’s marriage. His family was a melting pot of global perspectives, but this was a time in Western society when familial melting pots were not exactly embraced.

From his youth onward, Chong has felt the impact of such stigma. “I’ve been involved with those racial disparities all my life,” Chong says. It’s partly what drove him to the arts as a young man—this need to find a welcoming home somewhere in the churning class stratifications of the 20th century.

He found refuge in rock ‘n’ roll, and not to mention the heady effects of his first joint at age 17. After dropping out of high school, Chong started a band called The Shades, a name based on the musicians’ various skin colors. And he got in trouble, mostly because there wasn’t much to do for young men in that era besides play rock ‘n’ roll and get in trouble. On the orders of a local judge, Chong started The Shades Teen Club for local wayward youth. They were given the dance hall in the center of Calgary, which held a few hundred people. The Shades packed the house when they played. Chong knew he could command a room with his voice and his sense of skillful entertainment.

The Shades Teen Club attracted a rough crowd, though, and after a particularly rowdy night, the band was called to the mayor’s office. Chong thought they were going to get some kind of award, but instead they were kicked out of Calgary. It was a swift rebuke from the powers that be. “You guys gotta get out of town,” he recalls being told.

They hit the road and moved to bustling Vancouver, where Chong’s music career really took off. There, he met a young goofball named Cheech Marin. Over-the-top comedy and the guitar-driven rock of the 1960s offered a comfortable place for Chong to blend in. From there, showbiz kept Chong busy and successful for many years. Inevitably, Hollywood called.

As the world barreled into the 1970s and early 1980s, Cheech and Chong’s stoner jokes fit right in with a post-Vietnam malaise. They were a suitable foil to President Ronald Reagan’s ratcheting of the war on drugs.

After all, if you look closely, the duo projects a fairly positive image of the cannabis user in their movies. Chong’s character, Man, is a bodybuilder (who just so happens to still live at home) in “Up in Smoke,” the first of eight films he cut with Marin. He says now that it was a conscious choice to portray themselves as somewhat wellness-oriented, in tune with what he saw as the health benefits of a life spent enjoying cannabis. You can see the long-lasting ripple effects of this idea in the marketing materials of many extant cannabis businesses.

To a point, though, the world did move on from the heady “‘Me’ Decade.” The Reagan administration and the economic shocks of the 1980s altered the cultural attitudes of America. It would have been easy enough for the humor of Cheech and Chong—as a pair of characters, as an idea—to take a backseat, but instead, Chong’s career continued to thrive. To a younger demographic, he might be more well known for his role as Leo from “That ’70s Show”—or even for his stint on “Dancing with the Stars” in 2014.

By the time “That ’70s Show” was a major network hit in the early 2000s, Chong had already cemented himself in that elder statesman role. But this was still pre-Prop. 64, which passed in 2016. He had walked in both the mainstream of Hollywood and on the fringes of stage performance. He had found a home on both sides of the entertainment world, which is not an easy thing to do.

***

His iconoclasm developed into what today we would call a brand. Cheech and Chong, as a brand, is essentially synonymous with cannabis. Thus: Cheech & Chong’s Cannabis Company, a wide-ranging suite of brands and SKUs. To Gen Z social media-native cannabis customers aging into the legal marketplace right about now, he may very well be known solely for his house of brands.

Cheech & Chong’s Takeout, then, follows necessarily. After building out a portfolio of products with his longtime partner, the question became one of access: What’s the ideal way to get everything into customers’ hands?

The original goal was to open a brick-and-mortar dispensary, but the shockwaves of 2020 put the kibosh on building out a centralized retail setup. The world was changing fast.

“There’s the brand part of it, and then there’s the service part of the business,” says Aaron Silverman, chief brand officer of Cheech & Chong’s Cannabis Company. “The service part of the business was a no-brainer. Post-pandemic, everybody’s very comfortable, and if you weren’t comfortable getting your cannabis delivered beforehand, you probably are now. There’s not tens of thousands of points of retail distribution for you to go buy cannabis in California. Delivery just makes the most sense for most Californians to expect as a reasonably safe and reliable form of getting their cannabis.”

The brand part of it is exactly what Chong was hoping for: a distinctly personal touch in an industry that’s quickly becoming more transactional than he’d prefer. The brand side of the business builds the trust that’s vital for the service side of the business. The way he sees it, you can’t have one without the other, man.

Both sides of Cheech & Chong’s Takeout rely heavily on the direct input of the brand’s eponymous figureheads. California-grown cultivars don’t make it into the source materials of Cheech & Chong’s Cannabis products without the specific greenlight from the duo. Chong tends to gravitate towards flower more often than not; Marin is more of a concentrates guy. Along with Silverman and the brand’s chief product officer, their input is the valuable X factor needed to determine what’s going to make the final cut on Cheech & Chong’s SKU roster.

“Otherwise,” Silverman says, “we’re just another delivery service with a name licensed from a couple of celebrities, which we don’t consider them to be. We don’t. We’re not a celebrity brand—we’re an iconic brand.”

That may be the semantic difference that’s most important in describing Chong. Yes, his filmography is impressive. Yes, he’s a household name (as long as your household isn’t totally square).

Even in the late 1970s, Chong was asked questions about the far-off possibility of cannabis legalization. He was one of the early adopters whose voice really mattered in debates over that hypothetical. Of course, Chong couldn’t resist ribbing reporters: He told them that he’d be the richest person in the world if that day ever came.

Money is a small thing in the grand scheme of what this plant really represents, Chong says, the healing properties of its universe of chemical constituents. Those powerful forces cannot be surmounted by any inclination toward profit. Cannabis, Chong insists, can withstand the business interests of this current wave of legalization in America.

“People always talk about Big Business like it’s the Bogeyman: ‘Oh, once Big Business takes over…,’ or, ‘Once the pharmaceutical companies take over…,’” Chong says. “It ain’t gonna happen. The thing about cannabis is that it’s a gift from God—from the Creator. As gifts from God are, it’s very simple. Anybody can deal with it.”

What that sentiment amounts to is a certain paean to authenticity in this emerging industry. Anyone coming into this space would do well to understand that the culture of cannabis—a culture helped along by voices like Chong’s—brooks no compromise.

Besides: Chong is simply having too much fun to concern himself with the apparent rise of corporate cannabis. He’s here for the party.

***

But Chong’s life as entertainment ambassador for the cannabis reform movement wasn’t always so rosy.

In 2003, Chong and his family fell into the sightlines of the Bush administration’s crackdown on drug paraphernalia sales. Under then-Attorney General John Ashcroft’s Department of Justice, Operation Pipe Dreams rooted out glass pipes and bongs from head shops toeing the line of a marketplace that was vaguely defined and fell into a legal gray area ripe for exploitation.

Chong’s son, Paris, ran a California-based business called Nice Dreams that shipped high-end Chong Bongs to shops around the country. Federal agents set up a sting by ordering a shipment to a nonexistent store in the Pittsburgh area. Paris held fast against the suspicious order, but Operation Pipe Dreams was such an overzealous mission that DEA agents eventually worked their way into Nice Dreams as employees to ship the bongs to their counterparts in Pittsburgh.

While the federal crackdown targeted Paris and Chong’s wife, Shelby, it was Chong himself who took the heat—in return for the federal government not prosecuting his family members.

He was sentenced to nine months in federal prison.

A decade later, as Chong tells it, President Barack Obama offered to pardon Chong’s conviction. (This is after Chong initially started the pardon process, gathering thousands of signatures via an online petition.) Chong says he later declined the pardon. Embedded in a federal pardon is the stipulation that you did, in fact, commit the crime. You must show remorse. It’s a convoluted political process.

But Chong would not concede. He could not give in to the state’s narrative—even with a federal pardon dangling like a carrot in front of him. (CBT was not able to confirm this.)

Fighting the indictment in the first case would have cost a lot of time and money, and Chong knew that the Department of Justice at the time was hellbent on making an example out of him. He took the rap and made a point out of it.

“I would rather do the time and rub it in the noses of the authorities ever since,” he said, “and that’s what I’m doing.”

The years that followed Chong’s arrest weren’t so simple, either. Bouts with prostate cancer and colorectal cancer sidelined him throughout the 2010s, giving him a chance to put any medicinal claims to cannabis to the test. He touted the benefits of cannabis (along with a stringent diet and plenty of tango dancing), famously telling his fans, “I kicked cancer’s ass!”

By the end of the decade, Chong confirmed he was cancer-free.

These days, his upbeat personality and spry wit belie his age. He intersperses his conversations with hilarious stories from the past and the same brand of off-color humor that first landed him a shot at the stage. If cannabis is timeless, then apparently so, too, is Tommy Chong.

***

It is Aug. 22, 2022, in Las Vegas.

Chong has arrived in Sin City with his wife, his son and daughter-in-law, and his 2-year-old granddaughter. His old pal and lifelong comrade, Cheech Marin, is by his side, too.

The word on the street is that Cheech and Chong will pay a visit to Planet 13, a 112,000-square-foot dispensary located just west of the famous Strip. This is quite the get. Clark County officials declare Aug. 22 “Cheech and Chong Day,” and fans show up in droves. It’s the sort of public proclamation offered only to icons with some degree of mass appeal.

For decades, Chong has lived within the spotlight of a ravenous entertainment industry. He is fluent in the media relations work that accompanies brand launches and movie releases. He is comfortable in photo shoot settings. He is aware of the omnipresent gaze of fans, and he knows that he’s expected to be “on,” to be the funny guy.

And yet he is a humble man.

This is another thing about Chong that may not be surprising. Despite the years of success in Hollywood and in the American consciousness, he is not prone to ego trips. Who has time for that, anyway? When Chong talks about cannabis these days, he speaks often of God and sacrament and nature.

And as he talks, he comes around to the vast ecosystem of American politics in 2022. We are caught in a moment of great domestic strife, with presidents and past presidents alike tussling over the very idea of democracy. Chong knows how outrageous this conversation can be, harking back to his 2003 arrest and conviction. He knows how deliberately we narrow the scope of public debate, how earnestly we continue to make the same mistakes again and again. He was asked in the late 1970s what he would do if cannabis were ever legalized, and, despite answering then with his tongue in his cheek, the simple answer now is that he just doesn’t know: It hasn’t happened yet. We’re still stuck.

“What cannabis is gonna do—for everybody—is it’s gonna improve the brain power of a lot of bureaucrats that really need it,” he says. “Cannabis can’t help but improve the intellectual capacity of the citizens.”