“Those were the worst eight days of my life.”

It’s one of every illicit cannabis grower’s worst fears: the threatening sound of helicopter rotor blades cutting through the air above, perhaps searching the mountains in Humboldt County for cannabis grows or hovering over buildings in the heart of Los Angeles using thermal imaging or flare technology to locate concentrated heat sources that suggest indoor cannabis cultivation. The flashing red and blue lights of a police car, and the gut-wrenching whir of the siren that was sure to follow.

David Holmes knew that fear well. It’s a fear that has been shared by many of the estimated 68,000 California cannabis cultivators operating before adult-use legalization in 2016, and for others, still to this day. Many of those growers operated in what has become known as the state’s “traditional market”—the underground legacy market that has thrived for decades and become woven into the state’s culture and a term often used interchangeably with the so-called “gray market,” the California medical market legalized in 1996 through Proposition 215, under regulations that were anything but black and white. Despite doing what they could to grow legally, the murky regulations compelled legacy growers to essentially hide in the shadows—a daily weight they carried.

“Will today be the day they come for us?” Several California cannabis growers have confessed that this was their first thought upon waking each morning.

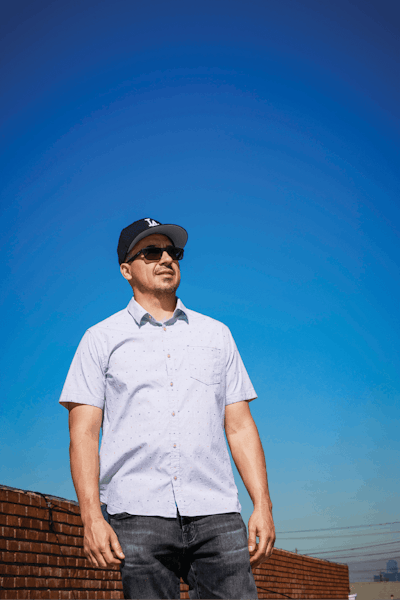

For Holmes—a former gray-market operator, and founder and CEO of Los Angeles-based licensed cannabis cultivator and consultancy Clade9—that fear became a reality and hasn’t entirely subsided in the state-legal, federally illegal U.S. cannabis industry.

The Raid

It was Feb. 6, 2013.

“I’ll never forget it because, I mean, obviously I got raided, but it was just before Chinese New Year,” Holmes says.

Holmes, who holds a master’s degree in mathematics from University of California, Riverside, had spent the day teaching math at Glendale Community College or Pasadena City College (he doesn’t recall which one, as he was teaching at both regularly) near his home in Los Angeles.

He drove from the campus to one of the cannabis cultivation facilities he ran in California’s gray market.

“I was just checking on things like I always did, talking to the trimmers and the team that was there,” he recalls.

He was about to drive to another cultivation site he managed, and that’s when it happened.

“I was always really careful,” he says. “This facility we were in, I was always real iffy about, because … it just seemed like it had a lot of heat there, like it was a little suspect. So I would be really careful about leaving with anything in my car, and that was usually my policy. So as I was leaving, my partners call me [from] the other [facility], and they’re like, ‘Hey, we need some clones. We’re short. Can you bring some over?’ And I’m like, ‘Yeah.’ And I put them in my car, and then I’m driving ….”

About five minutes into the drive through Los Angeles, Holmes sees flashing red and blue lights behind him and hears the whir of a siren. While it was clear he was being pulled over, he thought, “This could just be a traffic stop.”

But it wasn’t.

“The first thing the officer says is, ‘It smells like marijuana in here,’” Holmes recalls. “I was like, ‘Fuck.’ I know I’m fucked, right?”

“So the [drug-sniffing] dog is rummaging through the back, and of course he finds the clones. And then that was it. They arrested me.” – David Holmes

Holmes did what he had learned to do: “Just shut the fuck up,” he says. “I did my best. … But the cops were like, ‘Okay, get out of the car. Can I search your car?’”

“Nope,” Holmes replied. “You can’t search my car.”

“Everything I could do,” he says. “[But] they sat me on the curb and brought the drug-sniffing dog over.”

At that point, there were multiple police cars lined up behind him. “Oh yeah, it’s over,” Holmes thought.

“So the dog is rummaging through the back, and of course he finds the clones,” he says. “And then that was it. They arrested me.”

As the police car where Holmes sat handcuffed in the back pulled onto the road, Holmes saw his trimmer on the side of the road, also pulled over by police. Holmes realized immediately the warehouse was being raided, he says.

He was taken to an LA County police station, where, he says, he “had to wait four or five hours to get [a] phone call.” He wanted to call his wife.

During that time, Holmes says, “They were investigating. … First of all, they were getting a search warrant. … What I didn’t know is they were raiding my house as well. That was pretty brutal.” Holmes had a small research and development grow in his garage at the time, he says.

He had been married for 5 years and was father to a 4-year-old son and a 2-year-old daughter, and his wife and children were in the house when the police arrived, Holmes says, his voice faltering from its usually laid-back tone.

“It’s almost like all of this pain and suffering that people went through is for naught, because [a lot of] those old operators that suffered are now going to be out of business with the way California’s going.” – David Holmes

Everything was confiscated from the warehouse, and Holmes was arrested, released on bail, and given a court date, he says.

He raced home, and he says, “I saw my in-laws waiting there. I’m like, ‘Where are the kids?’ They’re like, ‘They’re gone.’ And then that’s when I found out my wife was arrested …. So then I had to get the money to bail her out the next morning. So she spent the night in jail.”

Holmes also found out that two of the trimmers he worked with had been arrested. “That was also painful,” he says.

It was now 10 p.m., and Holmes still was questioning, “Where the fuck are my kids?”

“Nobody knew where they were,” he says, shaking his head as if to shed the memory.

The next day, he found out his kids had been immediately placed in foster care through the Los Angeles County Department of Children and Family Services. “It was like, okay, we got to get them back,” Holmes says. “What do we … do?”

It was February 14, Valentine’s Day.

“It took seven days for us to get to [child] court. … It’s the scariest place I’ve ever been. They have your children hostage .... It’s crazy,” Holmes says, the laid-back Cali vibe in his voice now completely replaced with emotion. Holmes recalls that, at first, the judge had been threatening permanent foster care and adoption. “It was just like I was already guilty. And we were so scared,” he says. “… And my wife, God bless her, she put this incredible folder together that showed [pictures of] our family. It was done so well.”

Within 30 minutes, Holmes says, the judge had made his decision. “This guy is a professor at college. His wife is a teacher. They have a nice house. Why is the first play to take the fucking kids away?” Holmes paraphrases the judge’s comments. “Give them the kids back … immediately.”

“And so we got them back,” Holmes says. “It was horrific. But just to not know what the fuck’s going to happen. Those were the worst eight days of my life.”

The Gray Area

Holmes waited a painstaking three years through repeatedly postponed court dates and the district attorney promising that a charge was to come. But it didn’t. He was never officially charged because he had filed the legal paperwork necessary to operate in California’s medical market, where regulations allowed collective-style cultivation, “where you have a bunch of medical patients that can grow together,” he says.

Holmes started growing cannabis at some scale in 2002, after grad school. When he had “finally gotten serious, like warehouse style,” he says—after experimenting with small home grows and the 1,000 watt HPS system for R&D he had set up in his future wife’s garage—he realized, “Well I’d better … get a collective or I could be really in trouble here. So I hired an attorney, we drafted up a collective corporation and essentially tried to do everything the right way that you could in California at the time.”

The key word here is “tried.”

“The way it really worked,” Holmes says, “was you tried to do it right. But if the cops found out about you, didn’t like you, well, they could raid you. And it was like a, ‘raid, arrest, ask questions later’ policy. And that’s what happened. I mean, that’s what happened to everybody.”

Holmes says he got off much easier than many other growers who served prison time.

But the eight days where he thought he was going to lose his children was bad enough. “Every day I wake up and use that as motivation to keep going,” he says.

The Recovery: First Step, NASA

Mel Frank, famed cannabis author (whose books Holmes had read when he was first learning to grow), photographer, and a legend in his own right who has worked with Holmes on various cultivation-related research projects over the years, recalls the time of the raid and what followed. “I think it might have taken him five years and lawyers and everything else to finally have the police release his stuff back to him, which of course all was worthless now—the computers, stuff like that,” Frank says. “But he recovered from that.”

The first steps in Holmes’ recovery started before the final court decision on his future, and led him back to his mathematics roots.

“I got punched in the face, and then when someone picked me up, it was kind of nice.” – David Holmes

Prior to the raid, Holmes says, the head of the math department where Holmes was teaching had suggested that he apply for a faculty externship at NASA. “At first I was like, ‘No way. I don’t have time for that.’ … But when I got raided, I took a step back and was like, ‘I better do that. I definitely need to do that more than anything to show the judge that this guy isn’t a criminal.’ So the raid actually forced me into NASA, which is weird saying that,” he says with a laugh.

He applied and got accepted to work in NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. It was just what he needed after the raid: “I got punched in the face, and then when someone picked me up, it was kind of nice,” he says.

But when the three-month externship ended, he returned to his passion for cultivation. He took a job consulting for newly licensed Arizona cultivation operation Herbal Wellness Center, which he had been connected with through a friend, and hasn’t looked back.

“That was my first out-of-state consulting gig in cannabis,” Holmes says, and the first under what was, at the time, his brand Cannagen. (Holmes co-founded Cannagen with James Algeria, who continues to work with Holmes today, and the brand evolved into Clade9 in 2015.) “They were going to launch their cultivation, which is a 30,000-square-foot warehouse, and they needed someone to help them. … And then, it just evolved into an operational [contract].”

Holmes enjoyed working under Arizona’s clear regulatory structure, which was in stark contrast to what he had experienced in his home state. And in 2014, he began eyeing the up-and-coming Nevada medical market, which legalized in 2000 but hadn’t begun to rollout until nearly 15 years later. The state appealed to him as the new regulations had a similar structure to Arizona, he says.

“So I … went out to Nevada and started networking,” he says, “going to the cannabis meetings with the [state cannabis] commission, and networking with the local cannabis community. And I met some of the founders of Virtue [Las Vegas] before they were Virtue. They were looking to get into the cannabis space [and] looking for an operator, and I happened to fit the bill.”

Holmes has been contracted (under his Clade9 brand) for the past eight years to build and run Virtue’s 16,000-square-foot cultivation operation in Las Vegas—including hiring and training the cultivation team and developing the genetics Virtue takes to market.

“He had a great set up, … a mother room, cloning room, veg rooms, flowering rooms, drying rooms, processing, and all that,” says Frank, who recalls visiting Holmes at the newly built out Virtue facility. “He had set up a sequential grow, … so that you would always be harvesting every week or two weeks, and always starting new ones every week or two weeks. And you just had basically an assembly line grow system, which is what we had envisioned. And, of course, he had developed really good genetics.”

Virtue has about a dozen genetic varieties in its library, Holmes says, “but we focus on probably six to eight.” Clade9 owns all genetics; “I was really always tight with my intellectual property,” he says.

One of the varieties, Diamond Dust (a Bubba and OG cross), took home a first place People’s Choice award at the High Times Medical Cannabis Cup Nevada in December 2021.

The LA Story

All the while, Holmes never moved from his LA home. He commuted, flying each week from LA to Phoenix and then on to Las Vegas.

Shortly after California legalized adult-use cannabis in November 2016, establishing a framework for regulating licensed cannabis businesses, Holmes, his new business partner Kurt Parra, and some of their investors began working on a Clade9-owned facility in the City of Angels.

“California’s been a mess for 20 years in terms of the law,” Holmes says. “So it seemed like in 2018, ‘Hey, California’s finally getting its act together.’”

While Holmes had been growing cannabis for more than 15 years, the LA endeavor marked several firsts. “We had to find the space, apply for a license, receive the license, and then raise money and build it out,” he says. “I’d never done a project like that from the ground up …. Everything I had done up to that point was either my own—the cultivation operations, in the old days—or consulting. … So that was exciting, and nerve-racking, and scary. But we did it.”

Holmes and Parra raised about $4.2 million in a combination of equity and debt primarily through family and friends—“no institutional investment,” says Holmes, who learned valuable lessons during the process. “I definitely got to see the importance of financial modeling and projections and understanding the role of marketing and raising money. I learned a lot in that race.”

Once the capital was raised, Holmes and his then four-person team and a team of contractors gutted and built out the 17,000-square-foot facility (which Clade9 leased for a 15-year term with an option to renew), with the first crop planted in May 2020 and first harvest in August, according to Holmes. Today, Clade9’s LA facility has nearly 30 employees and sells product to approximately 50 retailers.

While Holmes is pursuing his passion, he says the past two years of operating in California’s legal adult-use market have been bittersweet, with memories of the raid and other sources of angst, such as making sure no one was following him after shopping for grow supplies. “Cops would literally post up at the hydroponic store and wait, and then tail people home, and people would get arrested that way,” he says, noting this was a more prevalent issue in the first decade of the 2000s.

There’s a lot of history woven into the largest cannabis market in the world.

“A lot of people have that history in California. There’s a lot of people who went through a lot worse than I did, for sure,” Holmes says.

And while adult-use legalization may have helped clear the regulatory murkiness, new challenges continue to plague cannabis cultivators. “They didn’t get it right the first time with medical. And now they’re totally dropping the ball recreationally,” Holmes says.

A combination of overproduction, weighty taxation, and massive competition from the illicit market formed a trifecta that has hindered the legal cannabis market from day one. In fact, the state was the first to see spending on cannabis drop after legalizing adult-use, according to a 2019 report by Arcview Market Research and BDS Analytics; the medical market had grown “to nearly $3 billion in annual spending by 2017, the biggest in the world,” the report states, but by 2018, “annual legal cannabis spending in the state slid to just over $2.5 billion.”

That report also estimated the state’s 2019 illicit market spending at $8.7 billion, compared to legal market spending of $3.1 billion.

Currently, the state’s cultivation tax—a tax on all cultivated cannabis that “enters the market”—is $10.08 per dry-weight ounce on cannabis flower, according to the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration, and the state’s excise tax is 15% (plus local municipalities add their own taxes to the mix).

“They should have had sort of a holiday on the taxes until things started to change around,” Frank says, suggesting the state hold off on taxing licensed businesses until the legal market essentially had a fighting chance. “Yes, people are willing to spend somewhat more for something that they know has been tested, that’s been clean, and that’s contributing to the tax base of the state. But they’re not willing to pay 40% more. That’s just the way it is. They’d just rather go back to their old supplier. So it is a mess here.”

Holmes, like many Golden State growers, is trying to weather the storm; but across the state, wholesale prices have been dropping anywhere from 50% to 70%, according to several reports.

“Strains that were selling for $3,000 a pound in summer 2020 are now selling for $1,000 a pound in some cases,” Holmes says. “Just last summer we were getting around $2,000 a pound. … And it’s almost like all of this pain and suffering that people went through is for naught, because [a lot of] those old operators that suffered are now going to be out of business with the way California’s going.”

“We’ve separated ourselves completely from the language of indica/sativa/hybrid, which is difficult because the language seems easier for consumers. In reality, though, terpene families are the future of flower product classification.”

While Holmes believes Clade9’s LA business will persevere, diversification is a feather in the company’s cap, helping to offset the market’s depressed prices. The operations/consulting arm of Clade9 just renewed its contract with Virtue Las Vegas for another five years, and Clade9 launched its own nutrient line—Newts—in 2020. Plus, Holmes has his sights turned East toward New Jersey’s recently legalized adult-use cannabis industry, where Clade9 has submitted an application for a cultivation license, and also toward New York, where Holmes says, “We’re looking at potential partnerships or we may submit an application, whatever gives us the best chance at operating there. We’re looking at the East Coast as a way to hedge against the craziness of the West Coast. California’s a mess for sure.”

While the company applied for but didn’t win a license in Illinois in 2021, Holmes says the experience taught him lessons he believes will help his chances in the coveted Garden State, with its cannabis market projected at $2 billion in year one, Hoodie Analytics’ Kelly Bernazza-Hall shared during a late 2021 Arcview webinar.

One lesson Holmes learned is the importance of having someone on the team “connected to locals,” he says, “either consultants or lobbyists that really had boots on the ground.”

As far as hedging his bets coast to coast, Holmes and the Clade9 team are “shifting the focus from bulk flower to branded, packaged flower products,” Holmes says. “Changing the strain mix to match the wants of the modern rec smoker. Reducing costs in the operation. Product development.”

Genetics and The Holmes Matrix

With competition high not only in California but across the industry, and particularly for craft growers competing with larger, more well-funded operations, Clade9’s focus on genetics is more important than ever. Holmes says he looks for “flavor, smell, color, structure, lab results, effects, yield, and overall smoker feedback” in any new genetics he introduces to his library.

To help guide him, he tapped his background in mathematics and devised what he calls The Holmes Matrix. While he won’t reveal specifics, he describes it as “a tool … to help me do selection for males. … For a breeder that’s doing what I’m doing, male selection is always critical,” he says.

“So you can look at the plant structure, and you can look at vigor and things like that. But one thing that is important with the male, that you can’t really see necessarily, is the terpene profile,” Holmes says. “The Holmes Matrix is basically [an algorithm that] takes the male’s terpene profile and gives you a better idea of what you want to select. It gives you a number, like, ‘Hey, this is a better choice if you’re looking for that.’ … Because in breeding, you have a lot of different things you might be looking to do. Each direction has its own choices, right? If you want to breed a high-CBD strain that has a lot of limonene, or if you want to breed a CBG strain that has a lot of caryophyllene, there’s all these choices you have to make to get there. So The Holmes Matrix helps with the terpene part of that selection.”

Holmes also sees a need to educate consumers, even if it means breaking from current norms. “The craft cannabis industry is super competitive. Product quality and consistency is important, but you also need to educate the modern cannabis consumer on why you’re different,” he says. “We’ve separated ourselves completely from the language of indica/sativa/hybrid, which is difficult because the language seems easier for consumers. In reality, though, terpene families are the future of flower product classification, and you’re starting to see the writing on the wall. The Emerald Cup and the California State Fair have adopted terpene classification for their flower categories in competitions.”

As Holmes advances through the legal cannabis market, he won’t forget his past. Clade9’s branding includes a helicopter image, a constant reminder to himself, the industry, and consumers of pre-legalization days with the helicopter-induced “heart palpitations,” as Holmes describes them. And the brand’s tagline, “Grown the Hard Way,” references that anxiety and “the pain and suffering that we had to go through as legacy operators to get to this point,” Holmes says. “But it’s also [that] growing it the right way takes a lot of time. And there’s a lot of experience that goes into creating a really craft flower product.”