Walking onto the Rogers Arena stage in Vancouver, British Columbia, Dan Sutton bore a distinct resemblance to a young tech-company CEO. Donning a long-sleeved black T-shirt, black pants, and black sneakers, his head shaved and face decidedly not, he struck the perfect Silicon Valley-esque balance between relaxed and serious, ready to crack a joke one minute and speak truth to the point of bluntness the next. He has something important to say—just not about iPhones or search engines.

“Why don’t we grow tomatoes in warehouses?” he asked rhetorically of the TEDx Vancouver audience. “Think about the word agriculture. Do you see images of smokestacks, concrete bunkers, factories? If you’re like me, you probably see rows of leafy green plants thriving in the sunshine.”

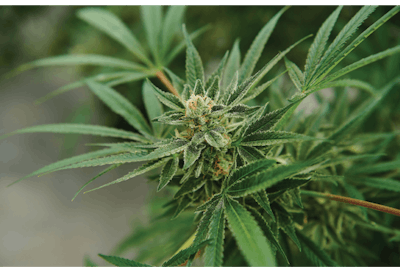

What Sutton said during the next eight minutes has come to define the ethos of his Vancouver-based company, Tantalus Labs. That is: the most sustainable way to grow high-quality cannabis at scale is outside, under the sun, in modern industrial greenhouses. To Dan, sun-grown is homegrown. “Plants thrive in sunlight,” he said with the confidence of an agricultural scientist. “They’ve evolved over billions of years to do just that. The sun provides a broader light spectrum and a higher light intensity than any artificial bulb.”

Though his audience responded with thunderous applause, this was quite a controversial position for a 28-year-old cannabis executive to take in 2015. Canada was still three years away from legalizing marijuana for adult use, and growers were just beginning to step into the light after decades of being forced to develop cultivation best practices underground. But that was beside the point to Sutton. The status quo had to be challenged because it no longer made sense to him.

Since that TEDx talk, Sutton, now 32, has become a rare phenomenon in Canada and in the North American cannabis industry—a genuine maverick CEO. Despite the diminutive size of his company compared with its peers, Sutton cuts an outsized figure on Twitter, the blogosphere, and television news shows, deliberately turning traditions upside-down or shutting them out altogether, zigging while everyone else is zagging.

Case in point: While most Canadian cannabis companies have either gone public or are priming themselves to go public on major stock exchanges, Sutton is content to keep Tantalus Labs private. While his contemporaries are trying to achieve massive national and international scale, buying up and building out physical infrastructure by the acre to exponentially increase their cannabis production, Sutton is almost single-mindedly focused on one greenhouse project in the Fraser Valley of British Columbia, called SunLab. And while most industry darlings are diversifying into new markets and developing a deep product portfolio, Sutton is building his company around the belief that the most powerful way to create value is to place quality over quantity. (Tantalus Labs has only seven cannabis cultivars—not hundreds.)

“We’re up to a bunch of weird and wild stuff, and we see the world through our own unique lens, but people seem interested,” Sutton tells Cannabis Business Times in an interview.

So, what exactly is Tantalus up to?

How can this small Vancouver LP realistically compete with the production output of publicly traded giants like Canopy, Aurora, or Aphria? How does Tantalus plan to grow? And why have investors been so patient with Tantalus’ relatively slow growth?

Every time Sutton is asked these questions on Canadian TV news or at industry conferences, he dodges, hints or teases, but never commits, suggesting with his knowing smile and raspy baritone that the questioner may be looking at Tantalus through the wrong prism.

“Not everyone is going to understand why it is you’re doing what you’re doing, but genetics is certainly one of my favorite aspects of the business,” Sutton says in the interview with CBT. “It’s a place where Tantalus Labs is making some pretty amazing investments, and not just financially. You’re going to see some really exciting stuff from us on that front—hopefully in the next 10 years but certainly over the next two years.”

As a successful entrepreneur and cannabis consumer himself, Sutton knows his clientele and what they want: a quality and consistent experience, whether that means treating a medical condition or eliciting a desired high or effect. He also understands that the experience depends largely on the genetics of the plant and comprises a company’s intellectual property—which can be transferred, legally, anywhere in the country. So, Tantalus may never need to achieve the production scale of a Canopy, Aurora, or Aphria, because producing might not be Tantalus’ end-game after all.

“I think we will always be a small-batch producer,” Sutton says. “Small batch in that we want to keep every harvest focused on a quality of plants that allows us to maintain a meticulous degree of control and commitment and keep doing new and interesting things that maybe have a degree of scarcity associated with them. What we’ve really learned over the last eight months since we’ve been in sales in the legal recreational market is that there is a far higher demand for Tantalus Labs’ cannabis than we could have ever anticipated.”

Viewed in this light, Tantalus’ SunLab greenhouse could actually be seen more as a lab than a production facility—a testbed to experiment with and perfect a small number of high-quality cultivars, which the company could then license to other growers in the region and perhaps even the world.

“This is our sandbox,” Sutton says of SunLab. “This is where we figure out our IP, where we figure out our systems, where we figure out our processes.”

Sutton’s Sandbox

A glimpse at the future for Tantalus Labs must begin at SunLab, the 75,000-square-foot “crown-jewel” greenhouse engineered to grow cannabis using the sun, fresh air and free-falling rainwater. The facility cost $10 million and took two years alone just to design. The company is currently in construction on a 50,000-square-foot expansion, which Sutton is optimistic will be completed by the end of the year.

SunLab also boasts a 98-percent crop-retention rate, Sutton says. He expects to produce between 2,500 kilos and 3,000 kilos (5,512 lbs. to 6,614 lbs.) of cannabis this year, and by expanding by another 50,000 square feet, the company could easily reach the 7,000-to-8,000-kilo (15,432-to-17,637-pound) range, he says. While this might sound impressive, consider that Canopy Growth, the largest publicly traded marijuana company in the world with a market capitalization of around $15 billion, has just over 4 million square feet of greenhouse-growing space in Canada, with three million alone in British Columbia, the company reports, and is on pace to hit 500,000 kilos (1,102,311 lbs.) of annual production, according to an article in The Motley Fool.

These comparative numbers are staggering—and sobering for Tantalus. But they also might be irrelevant, because the company has no plans to build more SunLabs across North America.

“You’re going to see a lot more partnerships,” he says. “You’re going to see a lot more collaborations. You’re going to see us sharing our IP, both from a production standpoint and a genetic standpoint, with other new entrants in the marketplace.”

A theoretical SunLab 2.0 would only happen if the plan fails—what Sutton calls a “backup option.” Still, he is bullish on his prospects. “I just think that there are so many beautiful greenhouses across the globe that we should be able to figure out which cultivars are going to thrive in those environments,” he says. “And leverage infrastructure that already exists, without the need to deploy capital, time and obviously infrastructure resources.”

Easier said than done. To develop high-quality cannabis cultivars and then build a business around licensing or sharing the IP to other growers, Sutton and his team have to prove that high level of quality consistently over time. That requires proof in the form of production.

“It’s about how many people we can touch with our product,” Tantalus Chief Financial Officer Luke Jenkins said during a November 2018 appearance on Valens GroWorks’ “Extracted” podcast. “We like to think that SunLab is this massive, amazing facility, but in the grand scheme of things, it’s not that big. And servicing the Canadian market is going to be a challenge for us at that footprint. Servicing the British Columbia market alone is going to be a challenge at that footprint. How we get our product to more people is going to be a huge thing that we think about over the next 12 to 24 months.”

Then Sutton, joining Jenkins on the podcast, interjected with one of his personal mantras: Start low and go slow.

A Bet on ‘Genetic Differentiation’

Early in that same podcast episode, co-host Kayla Mann said this about what Sutton and his team are up to in the Fraser Valley: “Tantalus is growing some of the best cannabis on the market right now.”

High praise, which, to Sutton, is a testament to Tantalus’ focus on a smaller number of cultivars, which he says helps achieve a higher overall quality for each of them.

Tantalus Labs produces only Blue Dream, Serratus, Skunk Haze, Harlequin, Cascade, Cannatonic, and Watersprite. The company went through a 16-month process with the Canadian Border Services Agency, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Health Canada, as well as foreign governments, lawyers and translators to import 150 different cultivars in about 20,000 individual seeds. That allowed the company to run its own phenotyping process. As Sutton explains it during the interview with CBT, “We were actually popping cohorts of these seeds and then selecting our favorite varietals, not necessarily ones that others were doing or what was on trend, but just things that we found interesting. That genetic differentiation allows us to deliver experiences to our users that are really difficult to find anywhere else.”

For LPs, one way to compete in the increasingly competitive world of cannabis is to license their IP to other growers. Intellectual property rights can go a long way in the monetization of cannabis-related ideas, products and services, but not if the end product is of average or low quality—or the same as everyone else’s.

“If you create something like Charlotte’s Web or some strain that is in extraordinarily high demand, and people want it everywhere and view you as having it locked down, then the IP could definitely be a revenue source,” says Vince Sliwoski, an intellectual property lawyer who manages Harris Bricken’s Portland office and teaches Cannabis Law and Policy at Lewis & Clark Law School. “Otherwise, licensees may be reluctant.”

Assuming Tantalus can meet its own high bar for quality, applying for a patent would be a next logical step. Then, only Tantalus would be able to make or sell the product, or license other growers to do so.

That patent could cover either the creation of a new or improved cannabis cultivar or make proprietary the way in which the strain is created. But a specific cannabinoid formulation, for example, cannot be patented unless it is “human-modified,” according to the recent ruling in United Cannabis Corporation v. Pure Hemp Collective Inc.

Unfortunately, there is not a lot of legal precedent to guide Tantalus’ IP strategy. In the United States, Biotech Institute LLC has the honor of the first utility patent to be awarded for cannabis breeding and production methods. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office granted U.S. Patent No.: 9,095,554 for the “breeding, production, processing, and use of specialty cannabis.” Since winning approval in August 2015, Biotech has filed a number of “child” applications, all claiming priority to that first cannabis strain patent. Meanwhile, in the first-ever cannabis patent infringement case, United Cannabis Corporation (UCANN) sued Pure Hemp Collective Inc. for infringing on its “ ‘911 Patent,” which covers liquid cannabinoid formulations of a purified CBD and/or THC greater than 95 percent. On April 17, Judge William J. Martínez of The United States District Court for the District of Colorado denied Pure Hemp’s Early Motion for Partial Summary Judgment. On May 22, federal Judge Nina Y. Wang denied Pure Hemp’s attempt to explain how UCANN’s patent is invalid. In doing so, the lawsuit proceeds. The cannabis industry is closely watching for developments in these cases, according to Sliwoski.

There are other IP-protection options, however. Tantalus could retain its intellectual property as a trade secret, or partner with other growers to share its proprietary cannabinoid/terpene ratios or the technology used to create branded products.

A patent would be preferable, as patents afford the most powerful IP protection, providing the owner with a temporary monopoly to exploit the invention. Patents protect new and non-obvious inventions (including plants, processes and machines), while trade secrets protect “patentable inventions,” which provide economic value to the holder if kept confidential.

The business case for a patent versus a trade secret is overwhelming. “If it’s just a trade secret and not a published patent, you don’t really know what you’re getting,” as a buyer, Sliwoski says. “A lot of the evidence for what these strains can do or achieve is anecdotal. It’s a hard market to be a buyer/licensee in.”

A Tantalus spokeswoman would neither confirm nor deny whether the company has sought any patent, trade secrets or any other IP protection.

A sensitive topic in cannabis circles, the protection of intellectual property has already exposed fault lines in the industry, with one side arguing against overly broad patent awards for practices and products that have been in place for decades, and the other trying to protect their interests in an ever-evolving global cannabis industry.

Where Sutton and Tantalus come down on the issue is unclear. But Sutton has already weighed in, if indirectly. On May 16, he sent three tweets, one aimed directly at Aphria: “@aphriainc is attempting to trademark the term ‘sungrown cannabis.’ I have no remarks on the matter at this time, save that I would bet that this will turn out to be a mistake.”

And another: “#Sungrown is for growers of all sizes who celebrate their natural environment and the fruit it bears. It is for the gardener and the greenhouse farmer. It is for the purity enthusiast. It is for everyone who told us it couldn’t be done. It is for all of us.”

And another: “So stand tall and be counted, and shout #sungrown from the rafters. Proliferate the story of the Emerald Triangle, the Gulf Islands, and the equatorial jungle. Natural cannabis is beautiful cannabis, and to celebrate sunlight is to celebrate all life.”

For Sutton, Sun-grown Is Homegrown

As the corporate leader, figurehead, and moral compass of Tantalus, Sutton is betting not only on his team of scientists to engineer revolutionary new cannabis cultivars; he is investing heavily in his home province of British Columbia, the strategy of greenhouses-as-a-testbed, and, of course, SunLab.

Four years after his TEDx Vancouver talk, Sutton is still ardently pro-sun-grown. And, for now, he says Tantalus has no plans to supplement cultivation operations with indoor grows.

“We are not going to be diversifying back into the indoor market,” Sutton says. “… Ultimately it’s economically not viable.”

Sutton is quick to point out that SunLab was designed to mitigate all the risks of outdoor growing by taking advantage of indoor-control technologies and being environmentally conscious. The roof of SunLab captures rainwater, which is then is triple-filtered and drip-line fed with added nutrients to each plant. No chlorine nor fluoride, nor pesticides for mold and pest control, are used. For airflow, SunLab features two 54,000-cubic-feet-per-minute, high-capacity airflow fans to pull transpiring moisture off the plant leaves—and more CO2 across the base of the plant.

Most critical for Tantalus’ growth ambitions, SunLab was built to accommodate different cultivars. “The more robust strains that we can grow, we can have other partners in a diversity of regions,” Sutton says. For two years, Tantalus has been conducting an analysis of the regions where cultivars would thrive and trying to recreate that environment at SunLab.

“The plants have certainly responded,” Sutton says, “and as a result I am now very, very much of the belief that the best-quality cannabis may today be grown indoors, but in the next five years it is absolutely going to be grown in greenhouses.”

Sutton also predicts that appellations will become the norm in the cannabis industry, just as they are in the wine market, and that certain global regions will become known for their cannabis vintages.

“Over the course of the next 10 to 20 years, individual regions will come to be celebrated for specific genetics,” Sutton says. Much like the Emerald Triangle in California, which supports more than 20,000 cannabis growers, according to Leafly, and is known the world over as America’s cannabis epicenter, British Columbia will have its own “genetic story.”

Tantalus is already in discussions with a number of family farmers that want to be in the legal cannabis business, Sutton says. “We’re good at Health Canada compliance. They’re really good at farming in their particular region.”

Next Steps for the ‘Lucky’ Maverick

For Sutton, this asset-light growth strategy speaks to a savviness borne of years in finance and IT, which adds to the incentive for Tantalus to stay private, at least for now. As a former investor relations director for a large publicly traded company, Sutton knows what going public means: selling equity instead of cannabis. During the past several years, he says has watched companies IPO and flop, reneging on promises to investors, the industry and consumers.

Until that time when public markets beckon, his investors will remain a closely guarded secret. During a recent appearance on BNNBloomberg, Sutton called them “the most elite groups of Vancouver entrepreneurs and business developers ever assembled for a local startup.” In the interview with CBT, he called himself “lucky.”

In Silicon Valley and in Vancouver, B.C., luck is the byproduct of hard work and vision, and maybe the ability to fly in the face of business-as-usual.

As Sutton said in a recent tweet: “Remember that those who truly drive change are rarely celebrated and often demonized by their peers. Take it from a guy who has never needed, and will never need, your fucking approval.”