The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office on June 13 published a series of applications from Biotech Institute, each seeking a plant variety patent for a specific cannabis cultivar. The documents were shared by MJ Patents Weekly, a USPTO public records service maintained by patent attorney Dale Hunt.

Biotech Institute, a California company, first filed a patent application for Lemon Crush in March 2018. Then, in August 2018, Biotech Institute followed up with patent applications for Cake Batter, Primo Cherry, Holy Crunch, Rainbow Gummeez, Guava Jam and Grape Lollipop. In November 2018, Biotech Institute filed a patent application for a “cannabis plant named Raspberry Punch.”

The USPTO has not yet issued any of those plant variety patents. Typically, it takes up to 18 months for the office to do so.

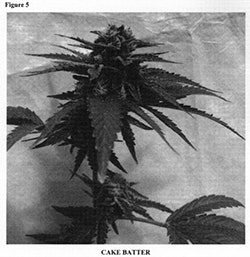

The patent application for Cake Batter, as an example, provides a detailed description of the plant, one with a maximum THC content of 6.5 – 14.21 percent and a maximum CBD content of 5.36 – 9.82 percent. “Physically, there are indications that its use may prevent some cancers and may prevent and/or treat disease,” according to the application. The main terpenes found in Cake Batter are limonene, beta-caryophyllene, beta-pinene, linalool, alpha-humulene, alpha-pinene, fenchol, myrcene, alpha-bisabolol and alpha-terpineol.

See the full Cake Batter patent application below.

The cultivar was grown via cutting and cloning in Biotech’s “greenhouses, nurseries and/or fields in Salinas, Calif.; Oakland, Calif; and/or Washington, D.C.,” according to the application, and derived from proprietary genetics. The initial cross of the company’s two parental cultivars took place in April 2016; the first clone of Cake Batter occurred in February 2017. The application includes photo documentation of the plant, as required by this type of patent.

biotech institute cannabis plant patent

biotech institute cannabis plant patentThe inventors listed on Biotech Institute’s plant variety patent applications are Mark Lewis, founder of NaPro Research, and Steven Haba, operations manager at Molecular Farms (a client of NaPro Research and a licensed cannabis cultivator in Salinas).

The applications come several years after Biotech Institute began making a name for itself in the cannabis industry for its claim on several utility patents, including Patent No. 9,095,554, which describes “compositions and methods for the breeding, production, processing and use of specialty cannabis.” More specifically, the ‘554 patent recites a non-myrcene-dominant cannabis chemovar that tests at higher than 3-percent CBD content. The ‘554 patent was issued in 2015.

A steadily increasing awareness of cannabis utility and plant variety patents—and the money and intent behind them—has prompted a growing discussion over the protection and the very meaning of intellectual property claims in what is still a fragmented industry. In April, Phylos Bioscience formally announced plans to begin a cannabis breeding program, and thus received backlash from corners of the cannabis industry that had bought into the company’s database of cannabis cultivars—the Phylos “Galaxy.”

In the wake of those headlines, the questions now turn to IP protection and the shape of the cannabis industry to come. Who will own what? What will it mean to breed and propagate a unique cannabis cultivar?

The matter of patents, as a public tool and as a defense of intellectual property, is up for debate. Utility patents, like the ‘554 patent, are one thing; plant variety patents, which home in on a specific plant, offer a more narrow interpretation of what’s to be protected.

“Variety patents, which are issued for all kinds of plants under the Plant Variety Protection Act of 1970, are issued only for plants that were asexually produced (clones) and are not found in nature, but rather the dedicated work of a breeder to create something new and unique,” as Kirk Miller wrote in a Cannabis Business Times article.

To date, only two specific cultivar patents have been issued. In April 2019, the USPTO issued a patent for a “cannabis plant named LW-BB1,” filed by Green Brands LLC in Denver, Colo. (doing business as LivWell, a licensed cannabis cultivation business). KUNC reported in May on the LivWell patent: “It was graded and evaluated purely on the merits of how well I described a plant,” chief scientist Andrew Alfred told the news station, “just as if it were a rose.”

Earlier, in 2016, the office issued a patent for a “cannabis plant named Ecuadorian Sativa” to a South Lake Tahoe, Calif., grower.

United States Plant Patent ... by on Scribd