Across the U.S., many pet parents fresh off the heels of Independence Day fireworks continue to look for solutions to pet anxiety during noisy or other particularly stressful situations. The federal legalization of hemp-derived cannabinoids took place in December 2018 via the signing into law of The Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 (commonly referred to as the 2018 Farm Bill). Despite the law’s novelty, a great deal more already has been discovered this year about how cannabidiol (CBD) works for humanity’s furry friends, including amongst the racket and chaos of a fireworks show. Whether doled out in tinctures, treats, or even capsules and topicals, the pet CBD market is diversifying and growing—quickly.

The three things to know about this evolving industry are:

- Pet owners look to CBD to address a range of conditions and symptoms their animals are experiencing—primarily anxiety, followed by pain (particularly joint pain/arthritis), and less commonly for skin conditions, seizure disorders and others.

- Though dogs have dominated the space traditionally, consumers are beginning to purchase more CBD-infused products for their cats, horses, birds and even smaller critters and reptiles.

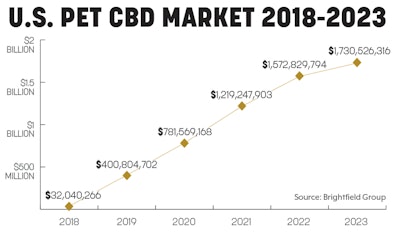

- As is the case in the human realm, a broad societal backlash against opioids and other pharmaceutical products—largely attributed to associated side effects and costs—has driven many consumers to seek natural health products for their pets as well. Accordingly, interest and revenues in the pet CBD space have blown up post-Farm Bill, as consumers feel more comfortable and better-informed about CBD and its uses. This paves the way for the pet CBD space to grow from a $32 million to a $401 million market over the course of just one year, according to predictive analytics and market research firm Brightfield Group.

Today’s market continues to be hampered by regulatory barriers, such as the FDA’s prohibition of ingestible CBD sales pending the establishment of an official, sanctioned regulatory framework, limitations placed on veterinarians by the DEA, and other state-level laws and policies.

Despite this, Brightfield Group anticipates the market will grow more than twelvefold in 2019 as a number of mass retailers are expected to onboard CBD products before the year is out, launching them into the public eye even more so than they are currently, giving significantly more consumers easy access to product and helping further destigmatize the use of CBD in animals.

Furthermore, in the medium-term, major manufacturers will join the space with tremendous resources and capital at their disposal, helping them more effectively and thoroughly tap into the $18-billion U.S. pet vitamins and supplements market, and further fueling the growth of the pet CBD industry.