Joseph Resnick wants to solve a problem that has plagued American ecological groups for three decades: He wants to eradicate the invasive quagga and zebra mussels from freshwater sources, from coast to coast. With microscopic extracts of cannabidiol (CBD), he may have the answer that thousands of people and billions of dollars have sought all along.

In December 2017, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation launched a prize competition seeking environmentally sound solutions to those invasive species’ rapid proliferation, one of the great ecological problems of this century.

Since those species were first discovered in Great Lakes ballast water in the late 1980s, neither public nor private ingenuity has devised a solution to their alarming and food chain-disrupting existence. In 2007, a man found a quagga mussel in Lake Mead, 30 miles east of Las Vegas. The problem had clearly surpassed the bounds of the Great Lakes, and it’s only gotten worse. The Columbia River watershed, in the Pacific Northwest, is the last watershed known to be free of these mussels in the lower 48 states.

After a lone quagga mussel was found in Lake Mead in 2007, observers noted that the population had exploded into “the trillions” by 2009, according to the Associated Press. Each female, to be clear, has the ability to lay 30,000 eggs per breeding cycle.

A thriving population of these mussels will inevitably drain an ecosystem of its plankton, out-competing most fish species and causing a breakdown in the food chain. Because they stick to surfaces, like pipes or piers, the sheer mass of mussel colonies can also destroy public infrastructure.

The federal government needs a solution as quickly as possible.

“I’ve been involved for the last couple years here in developing new uses and processes for cannabis,” Resnick says. “I became interested in using cannabidiol as a method of treating this invasion of quagga mussels and zebra mussels that has actually plagued the United States for the last 30 years.”

As the emeritus chief scientist of RMANNCO, he’s leading the innovative delivery system behind this CBD project. If his plan works, the U.S. government may find that CBD—a Schedule-I banned substance, in its eyes—can solve the problem of quagga and zebra mussel reproduction, a multi-billion-dollar fiasco for American businesses and communities.

With a full career of innovative technology under his belt—covering the depths of nano-particulate matter to the final frontier of outer space at NASA—Resnick plans to encapsulate powdered cannabinoids in “microspheres,” made of a natural biopolymer, and transport the chemicals directly to the mussels. “It’s the damnedest thing you’ve ever seen,” he says.

The biopolymer itself 1.8 times heavier than water, and Resnick also fills his microspheres with sulfur hexafluoride, which is six times heavier than air. Those density measure are important: This is how Resnick gets his cannabis product to the mussels.

“Consequently, [the microsphere] does not float. It sinks in water,” he says. “Imagine if you will a BB. Imagine taking a handful of BBs and dropping them in the water.”

This is a key point of differentiation between Resnick’s plan and the ecological remedies that came before: Resnick’s microspheres can sink to the underwater areas where mussels actually thrive. The “benthic zone” is the lowest region of a body of water, reaching up to as much as 18 inches below the surface. Anyone who intends on eradicating quagga and zebra mussels needs to get down there. Past efforts to combat these invasive species have often involved dumping various toxic biocide agents into the water and hoping that the chemicals spread sufficiently to the mussel population.

It hasn’t worked.

“You’ve got to treat these things where they live,” Resnick says.

Inside his microspheres, he’s included nanospheres that contain miniscule extracts of CBD. In powdered form and in sufficient quantity, Resnick says, CBD prevents mussels from producing the chemical that allows them to “stick” to surfaces, like the hull of a ship. If mussels can’t stick, or anchor themselves, to a fixed surface, they can’t feed. And if they can’t feed, they die.

As a back-up to his plan, Resnick has also included a strain of genetic virus in his nanospheres. This gene-editing chemical would essentially strip the mussels of any ability to produce offspring that can stick to surfaces and, therefore, feed.

In one way or the other, he points out, he’ll either end the mussels’ line of existence in this generation or the next.

The Bureau of Reclamation has not yet announced the winners of the first stage of the Grand Challenge, which is a “theoretical challenge,” a white paper. If Resnick’s project were to win approval, he would move to the second stage: a laboratory-scale demonstration.

Resnick sees big opportunities in this cross-section of scientific inquiry. “There’s nothing greater than to be needed,” Resnick says. “And to realize and to see that what you do is really helping people and it’s important. I’m not self-aggrandizing or anything like that, but it makes me feel good to know that what I’m doing helps people.”

Despite its federal status as a banned substance, CBD is permitted as a biocide for use on invasive species, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. But Resnick didn’t have quagga mussels in mind when he first embarked on his work with the cannabis industry. It wasn’t the Grand Challenge came along that he saw an immediate connection among all of his previous scientific research.

In the cannabis world, this work started a few years back for RMANNCO and Resnick, when he began working with a company in California to manufacture encapsulated powdered cannabinoids.

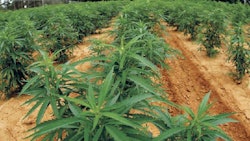

Back in North Carolina, where a nascent hemp industry is growing, Resnick taking a closer look at how hemp oil might be used across a spectrum of public and private organizations—as fuel, for instance. As the country’s social attitudes and laws have begun to accept casual cannabis use, Resnick’s interest in cannabis has turned more toward the ramifications of dosing.

By encapsulating cannabinoids in, for instance, the sort of biopolymer microspheres that Resnick produces, he can guarantee accurate measurements. This will prove vital not only in his work with invasive species, but with the broad spectrum of consumer and patient cannabis uses, as well.

“Dosing is a very, very big issue in the cannabis edibles industry,” Resnick says. “And, essentially, that’s why I got into this.”

Top photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Zebra mussels line the shoreline of Lake Michigan.