Dan Sutton, founder and CEO of Tantalus Labs, a Vancouver, British Columbia-based cultivator, says that tax is by far the company’s largest line item, costing more than all its employees’ salaries and about five times as much as its crop inputs and production costs. He says the high cost of taxation has forced some producers to choose between paying their taxes or keeping their lights on.

The tax structure is just one of many economic conditions challenging licensed producers in Canada’s 4-year-old adult-use cannabis market—oversupply, price compression and the still-thriving illicit market have also hit businesses, especially small businesses, hard.

While GreenSeal and Tantalus have stayed afloat through brand differentiation and unique product offerings, Niles and Sutton say that other smaller, craft producers have not been so lucky.

“We’re better off than most,” Niles says of GreenSeal. “We operate at probably about a 50 percent or so gross margin for our business and … we do have a net profit, which seems to put us ahead of the vast majority of other cannabis companies.”

The Canadian government announced in September 2022 that it launched a review of the Cannabis Act, the federal adult-use legalization law that took effect in October 2018, to evaluate the statute’s impact on youth, indigenous communities, the economy, the illicit market and more.

The review, mandated by the Cannabis Act itself, is being conducted by a five-member Expert Panel, which government officials appointed in November. The panel will ultimately advise government officials on progress made toward achieving the goals of the Cannabis Act—which include protecting the health and safety of Canadians and establishing a diverse and competitive legal industry to displace the illicit market—as well as identify any areas of improvement.

A report with findings and recommendations may take up to 18 months to produce, and operators worry about the fallout. Immediate reform is critical to the survival of operators and the legal, licensed market, they say.

RELATED: ‘Rounding the Corners:’ Reviewing Canada’s Cannabis Act 4 Years Later

Sutton is a member of Stand For Craft, a national organization made up of 40 small producers that have been advocating for a more progressive tax policy—based on policies in the Canadian craft beer and wine industries—in the Canadian cannabis market. He says the organization was born from a collective awareness that the current tax structure disproportionately harms small businesses.

Stand For Craft aims to analyze the economic aspects of Canada’s market and provide data that Sutton hopes will facilitate policy reform. The organization submits commentary, data and analysis to Canadian regulators on a weekly basis, Sutton says.

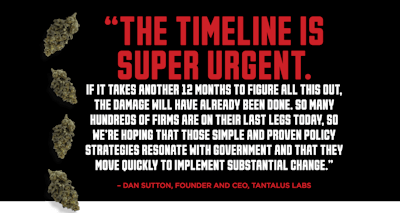

“The timeline is super urgent,” Sutton says. “If it takes another 12 months to figure all this out, the damage will have already been done. So many hundreds of firms are on their last legs today, so we’re hoping that those simple and proven policy strategies resonate with government and that they move quickly to implement substantial change.”

In the meantime, Canadian producers foresee a tough year ahead.

A Market Transformed

When adult-use legalization took effect in 2018, Niles says it “was a wonderful time in the industry.” Capital was flowing into the space, there were fewer licensees and SKUs in the market and therefore less competition, and Niles says some of GreenSeal’s most profitable days were in 2018, 2019 and 2020.

“And there wasn’t the same price erosion,” he says. “We’ve seen the price of a gram of cannabis dramatically fall, both in wholesale channels and at the retail stage. There have been massive, massive changes.”

Sutton agrees that the industry was more economically stable at the start of adult-use sales.

“The prospects of legalization were optimistic, but since the outset, few firms have generated free cash flow, and none have generated it consistently,” he says. “Prices have continued to compress in competition with the unregulated and untaxed illicit market, while tax has grown to be a bigger and bigger piece of the margin pie.”

Rick Savone, senior vice president of global government relations for Aurora Cannabis, who also serves as chair of the Cannabis Council of Canada (CCC), told Cannabis Business Times in October 2022 that depending on the product, “anywhere from 45% to 50% of the product prices go into government coffers in one form or another.”

“That does not allow us to compete with illicit producers whose prices are way, way lower and whose potency is often higher,” Savone says.

In a follow-up email to CBT, Savone added that the market has not unfolded in a way stakeholders would have hoped.

“Promises of the past and belief that government would abandon prohibition-era politics have not been realized,” he says. “The legal industry faces excessive and unsustainable taxes, regulatory hurdles that are nearly impossible to navigate, and many licensed producers are in a dire situation. Government is ignoring the needs of this sector, which provides tens of thousands of jobs and pays significant tax. We need a government that shows up in a real and modern way for our industry.”

Niles says that relatively low-interest capital and low inflation “taped over a lot of the cracks” in the market in the short term, but rising interest rates and the increased cost of materials, crop inputs, packaging and ancillary services have since distressed many businesses.

“Their revenue is not keeping up with their expense load,” Niles says. “They’re having a challenge right sizing their business economically. And they’re going to be very pressured, in my opinion, for the next 18 to 24 months.”

Canada’s cannabis industry is the most strained it has ever been, he says. So, what has changed since the early days of legalization to cause such tension?

Shifting Economics

Niles and Sutton point to high tax rates—particularly the federal excise tax, which is a minimum of CA$1 per gram on fresh and dried cannabis—as one of the biggest pain points in the market.

Niles and Sutton say that when the federal government set the tax rate, officials also set the wholesale cannabis price at roughly CA$10 per gram.

“[The tax rate] makes sense at $10 [per gram], and everyone was OK with that, but then the prices have gone down by 50 percent, 60 percent, 70 percent—maybe more on some products—[and] then all of a sudden, a flat fee doesn’t make a lot of sense,” Niles says.

If the market price per gram dips from $10 to $4, for instance, then the effective $1-per-gram excise tax rate increases from 10% to 25%.

Sutton says he isn’t quite sure how the government decided on the flat rate for the excise tax, but the rate is not sustainable for small businesses, and change is urgently needed.

“...The wholesale price of cannabis in Canada ... today has fallen to about $4. Now, the problem is that because of the belief that high, high prices would be perpetual, Canada taxed it as a minimum of $1 per gram, which is now representative of [25] percent of a producer’s top line revenue in a month,” he says. “It has pushed all the small businesses to a place where they actually have to take money and take losses every month to just get their products to market.”

Oversupply also contributes to the industry’s troubles, according to Niles and Sutton, challenges that are familiar to state-legal operators in the still federally illegal U.S. market.

When Canada legalized adult-use cannabis, the consumer demand that was initially projected drove many of the larger producers to expand their infrastructure to support what Niles says ended up being “way, way, way out beyond what was ever going to be the basic demand in Canada.”

“They were producing way, way, way more than this market could ever absorb,” he says.

But the problem extends beyond producing more cannabis than consumers are buying; Niles says there is also overproduction of high-THC products, trying to draw in consumers shopping by potency rather than introducing more dynamic choices.

“I see a lot of people … try to introduce a 20-percent THC flower product with low terpenes on a strain that’s been in the market for a long time,” he says. “There is so much of that out there right now. It’s an incredibly crowded product. There’s probably a ton of overproduction of those sorts of products, but then there’s probably a dramatic underproduction of different products.”

Another roadblock Savone notes are restrictions to marketing, which limit producers’ ability to educate consumers.

“When we are unable to educate consumers directly, they rely on informal networks to understand how to best use the products,” Savone says. “They also develop relationships with the illicit market, who market directly to children, use illegal pesticides and underpin criminal elements of society.”

He adds that the ability to market the distinct attributes of individual products would benefit both consumers and brands.

“We’re not able to market to consumers. We use plain packaging, and the only thing we can say about our product is its name and its potency,” Savone said in October. “That doesn’t really help consumers to understand about the potential of the product, how it could be used, or what distinguishes our product from another competitor’s products.”

The illicit market also continues to plague licensed operators by taking market share from the legal industry.

“First and foremost, the illicit market will always have a pricing advantage,” Sutton says. “Right now, it has a substantial pricing advantage. If you want equivalent quality cannabis from a legal source, you’re likely going to pay 30 to 40 percent more for the legal option. If that number was 15 percent or 10 percent, it would make a ton more sense for consumers who are on the verge of wanting to switch over from illicit sources that are untested and unregulated but nonetheless sufficient to meet their needs.”

Preparing For The Worst

Niles and Sutton both say despite the challenging year forecasted, they believe some of the business decisions they’ve made will protect them from the potential fallout, and could be useful tips for others to navigate 2023.

“I’m reasonably optimistic about GreenSeal,” Niles says. “We’re launching new products. We’ve got some really interesting stuff coming out. We were already kind of battle-hardened from an economic perspective based on how we set up the business in the first place, … but I’m not arrogant enough to think that we’re an island here. We’re all part of the same industry and the same community, and, outlook-wise, I think it’s going to be a very, very challenging calendar year in 2023.”

From GreenSeal’s perspective, Niles says he always planned for the world in which Canada’s cannabis businesses currently operate.

“I think that’s one of the reasons we’re better off than most, is because we knew the good times weren’t going to last, and we made a lot of strategic decisions on the economic front to be positioned to withstand the storm,” he says. “We always like to joke, Noah built the ark before the rain, not after it started raining. It’s the same thing for us.”

Niles says GreenSeal tried not to overextend its business through taking on high-interest debt, hiring extra staff or expanding its cultivation operations—all of which he says ultimately led to businesses making cuts now that supply is greater than demand.

“All of these things contribute to an expense runway, which is no longer really justified in the cannabis space at this stage,” he says. “And unfortunately, that’s meant a lot of job cuts for people, a lot of facilities shuttering.”

Canopy Growth, for example, has taken several steps in the past year to cut costs and streamline its business; the company announced in a press release in early February that it would cease cultivation at its flagship Smith Falls, Ontario, facility and cut roughly 800 jobs. In September 2022, CBT also reported that Canopy sold 23 of its Tweed and Tokyo Smoke stores in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Newfoundland and Labrador.

Tilray is also grappling with the industry’s oversupply issues, with chairman and CEO Irwin Simon, during a Jan. 9 earnings call, discussing the possibility of allocating cultivation resources to fruits and vegetables to weather the industry’s economic storm, CBT reported in January. Tilray did not respond to multiple requests from CBT for comment.

Alberta-based SNDL Inc. (formerly Sundial Growers Inc.) announced in mid-February that it had also initiated cost-saving measures that include laying off roughly 85 employees.

Like Niles, Sutton has taken a lean approach to Tantalus, saying that his business plan for 2023 is “hope for the best and prepare for the worst.”

“We have streamlined our costs, honed our labor spend and reached new levels of efficiency to weather this storm,” he says. “It is hard to imagine a scenario where cannabis prices in Canada grow in the medium term, so [a] lean mentality seems essential to survive in this uncertain future.”

Tantalus has an 80-person team that Sutton says does the work of 120 people.

“We want to stay on the playing field,” he says. “We want to continue to deliver value to these customers. But even our destiny isn’t assured. We look like we could be a survivor, but one bad quarter could throw us right off the playing field. We’re playing on a knife’s edge.”

To keep its product offerings fresh and exciting for consumers, Sutton says Tantalus plans to pursue new product categories in 2023, including infused prerolls—one of the few areas where sales are growing—and multipack prerolls that feature unique flavors, effects, and a “smooth consumption experience.”

“For Tantalus, when we look at new products, … we think about, for flower and prerolls, where are there flavor gaps? Where are there potency gaps? Where is a customer need that we’re aware of that isn’t getting serviced?” he says.

Sutton says Tantalus has built its brand reputation on “clean-smoking, high-potency” flower that not only delivers a potent effect, but also has a nice flavor.

Tantalus has grown consistently over the past year, with 2022 being its strongest sales growth year to date, although price compression and the increased relative share of its tax revenues have kept the company’s margins lean in order for it to stay competitive.

“There will inevitably be a lot of consolidation this year, a lot of [Companies’ Creditors Arrangement Act] CCAA filings, bankruptcies, insolvencies, bad debts, predatory consolidation—that’s all inevitable, no matter what policy changes,” Sutton says. “But the glimmer of hope is if this policy can be agile and reactive, it … will create structural changes, especially for the small businesses in the industry, to show them a path to be able to deliver value to their customers.”

The GreenSeal team has also worked to differentiate the company by offering unique products that fill gaps in the market.

“If you walk into a store and you talk to the budtenders in that store, they can probably rattle off the top of their heads a list of products that they don’t have that they’d like to see, and that’s the stuff that’s underproduced,” Niles says.

GreenSeal’s staff has relationships with several retailers whom they routinely reach out to with questions like: Would you buy this? Do you think your customers would buy this? Where would you want to see the price? Where would you like to see the terpenes? Where would you like to see the THC potency?

GreenSeal recently launched a new cultivar called Pink Octane, which Niles describes as a high-quality, gassy strain, a move to meet what they heard consumers wanted.

“We kept hearing from the market they felt there was a real gap in a high-end, high-quality, gassy strain because there’s been a lot of bias … in the market toward fruity strains, citrusy strains, or earthy, woody strains,” he says. “In our market, we were talking to budtenders, we were talking to customers, and they said, ‘Yeah, we could really use a high-quality, gassy strain—that would be really good.’ So, we said, ‘OK, let’s bring that back internally. How can we grow that? How can we price it?’”

Pink Octane was released in multiple provinces, including Alberta, Ontario and Manitoba, in January and February. It was available in 3.5-gram packages of flower and 10-packs of 0.35-gram prerolls at launch, and will be available in 14-gram flower packs and three-packs of 0.5-gram prerolls in the coming months. Niles estimates that GreenSeal has sold tens of thousands of units across all provinces and formats so far, and Pink Octane initially sold out within five days of its launch in Ontario.

A Call to Action

As cannabis businesses continue the struggle to survive across Canada, the legislative review of the Cannabis Act is underway. Officials are expected to present a report on the review’s findings and recommendations in both houses of Parliament within 18 months, according to a statement Health Canada provided to CBT in late January.

The Expert Panel conducting the review plans to provide advice to the Minister of Health and Minister of Mental Health and Addictions on progress made toward achieving the Cannabis Act’s objectives, as well as feedback on areas to improve the law’s overall function, according to the statement.

The online questionnaire to gather public feedback on the Cannabis Act was open to all Canadians from Sept. 22 through Nov. 21, 2022, and Health Canada indicated that it received more than 2,000 responses, which will be summarized in the final report.

The panel will also continue to engage with the public through “in-person engagement sessions and ongoing dialogue with key stakeholders and experts in relevant fields,” according to Health Canada.

The report will be made public online “in the coming months,” according to the statement, and will ultimately help inform the Expert Panel’s findings and recommendations.

Savone says simplifying the regulatory model is imperative to ensure businesses can thrive.

“We need to lower the regulatory bar so people can access the products they want and need,” he says.

Sutton is concerned about how long it will take the government to implement meaningful reform.

“The time for action is now,” Sutton says of the legalization review. “It’s been four years since legalization, and we’ve been slow to move on readjusting critical policy elements.”

Whatever change comes from the review of the Cannabis Act, Niles and Sutton say they would like to see tax policy reform as soon as possible.

“The tax regime is definitely in need of some sort of review and overhaul,” Niles says. “Taxation’s not going to go away. For me, it’s more about fair and equitable taxation that can be built into a reasonable cost of doing business.”

Instead of a flat fee, Niles and Sutton would like to see the excise tax calculated as a percentage of cannabis operators’ revenue.

“What the right percentage is, is up for debate, but it needs to be geared more toward a percentage of what’s happening in the space,” Niles says. “If prices go down, your percentage stays the same but your dollar out of pocket goes down and you can plan accordingly from a market perspective. I think that’s a major, major change that pretty much everyone in the space seems to be calling for to greater or lesser degrees.”

Lessening the tax burden on licensed operators would also help them better compete with Canada’s still-thriving illicit market, Sutton says.

“Otherwise, we’ll never be close to perfectly competitive,” he says. “We’ll never have a reason for those consumers to cross that chasm.”

Reduced taxes could also help illicit operators transition to the legal market, Sutton says.

“I would guess that 95 percent of illicit growers, in their heart of hearts, they want to be in the legal system,” he says. “They want to make it work for themselves, they want to make a legal career out of it, and they want to come out of the shadows. But how can we expect them to do that if we don’t have a case study, 10 case studies, 50 case studies of businesses that are financially survivable? And if Tantalus Labs can’t make that happen perfectly every month, then how is some five-person grow op going to do it? They would be daunted, and justifiably.”

Looking ahead, Niles says his biggest fear is that even if the legalization review leads to changes in policy, relief may come too late for many operators who are on the verge of insolvency.

“I’m confident that long term, it will equilibrize and something will be found that makes sense, but how many businesses will be lost between now and then?” he asks. “That’s my great fear, that the government doesn’t move as fast as the industry does. Relief was needed yesterday, not two years from now.”

In the meantime, Niles expects production capacity to decrease in the medium-to-longer term and the oversupply problem to correct.

“People will get more adaptive at putting products in front of customers that they really want, so that will adapt in time,” he says, adding that federal and provincial regulators still have a large role to play in helping the market find its footing.

“I’m optimistic in the long term about this space,” Niles says. “People want cannabis products. People want to consume. From what we’re seeing, consumption has either stayed flat or gone up pretty consistently since legalization. So, the industry’s not going anywhere. I think it’s about: how do we make it a fair and equitable and reasonably profitable space? These aren’t charities. People need to actually turn a profit to reinvest in their business and to reward shareholders.”