California’s new cannabis regulations allow businesses to deliver cannabis in jurisdictions that have banned commercial cannabis activity, but those jurisdictions have filed a lawsuit to regain local control.

When California voters passed Prop. 64 to legalize adult-use cannabis, they established a vertically integrated supply chain that allowed cultivators, manufacturers, distributors, testing labs and retailers to operate—and the retailers were allowed to implement delivery services. Prop. 64 also authorized jurisdictions throughout the state to control commercial cannabis activity within their borders—either through adopting regulations or banning commercial cannabis activity altogether. Now, jurisdictions that have banned cannabis have sued the state, arguing that they should also be allowed to ban cannabis delivery.

“At this juncture, I would say three-fourths of the jurisdictions in California, which is over 500, are what we call banned jurisdictions, which means they do not authorize any commercial cannabis activity within their jurisdictions,” Robert Finkle, senior counsel of Greenspoon Marder’s Cannabis Law Practice Group, tells Cannabis Business Times. “And what a lot of them believe, at least the ones in the lawsuit, is that this also includes the ability to ban delivery within their jurisdiction. And that’s [delivery] from operators in non-banned jurisdictions [that are] taking cannabis and delivering it into a banned jurisdiction.”

Since the legal adult-use cannabis marketplace launched on Jan. 1, 2018, the Bureau of Cannabis Control (BCC), in collaboration with the Department of Public Health and the Department of Food and Agriculture, have created rules and regulations for the state’s cannabis industry, which were formally adopted in a final form in January 2019. The rules allow cannabis businesses to deliver to cities and counties that have banned commercial cannabis activity, as long as they are compliant with state regulations and the regulations in their home jurisdiction. This authorizes them to transport cannabis goods through any jurisdiction in the state.

“I think that makes a lot of sense because there are cannabis consumers throughout the whole state of California—it doesn’t matter if you live in a banned jurisdiction,” Finkle says. “There are cannabis consumers that live in banned jurisdictions, and they should be able to access that market. They probably voted in favor of Prop. 64, but their local jurisdiction won’t let a storefront pop up, or won’t let a cultivator, manufacturer or distributor pop up. Well, fine, but … why would local jurisdictions all of a sudden be able to force cannabis consumers within that jurisdiction to have to travel to another jurisdiction to get the cannabis goods that they’re seeking?”

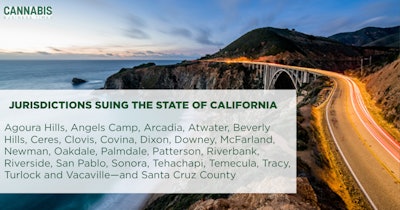

The 25 cities and counties included in the lawsuit are relying on Prop. 64’s local control provision, but the statute also prohibits municipalities from banning the transportation of cannabis through their jurisdictions, Finkle says. They, however, have interpreted the law to mean that they can disallow delivery within their jurisdictions.

“You’ve got to wonder what these banned jurisdictions are really worried about,” Finkle says. “They don’t have to have a storefront in their city, which is one of the things they don’t want to see. … They don’t have to allow the business to operate in their jurisdiction and create the smells and the nuisances that they’re concerned with. … They get to ban all of that.”

Banning delivery services, too, would leave many customers, especially medical patients with limited mobility, unable to access the market, says Shea Alderete, CEO of distillate manufacturer GenX Biosciences.

“I used to grow CBD for cancer patients,” he says. “Without me being mobile and being a caregiver for them, they wouldn’t have gotten the medicine they needed.”

In addition, a delivery service is arguably a safer alternative to having a cannabis consumer traveling to purchase products, Finkle adds.

“Why would they want a consumer to have to drive to some other place, potentially using the cannabis goods, and drive back?” he says. “Delivery companies are actually held to very strict standards regarding delivery. … They are regulated such that it would make it safer, in my mind, for a delivery driver to bring it right to the home of the consumer. I think that’s really the whole theory underlying delivery in the first place.”

Not to mention, Finkle says, that cannabis consumers living in jurisdictions that have instituted bans could live miles away from a city or county that allows cannabis retail.

“It’s always been about safe access here in California, and you have to imagine that delivery is one of the best forms of safe access,” he says. “If there are people with medical needs, if there are people who want to endeavor for some adult-use, [then] they can have it delivered to their house. They don’t have to get in a car and drive somewhere and put themselves at risk or other people at risk. Maybe they have a medical condition hampering their ability to do that. It just doesn’t make a lot of sense what they’re trying to do.”

And it’s the cannabis consumers and patients who ultimately suffer due to the legal in-fighting, adds Alderete. “I think the biggest issue is the educational platform,” he says. “There’s no road map. There’s no real guidance from the regulatory board on who is legal and who isn’t legal. So, I think that poses the biggest challenge for our marketplace.”

Delivery is not only important for consumers, but also the state’s cannabis businesses that have made delivery services a large part of their business model, according to Katy Annuschat, an attorney at Snell & Wilmer.

“It’s hard for those businesses to operate profitably if they aren’t able to deliver to consumers outside of their jurisdictions,” she says. “If you’re in a city like Portland or Denver, it may just be just as convenient for you to go to the store as it is to wait for a delivery driver. But in Southern California with traffic or just by the length of distance you have to travel to get to a store, delivery is an important option for consumers. Consumers have been reliant on that, even before we had this rule passed, when we were still in the medical marijuana business days. A lot of those consumers were reliant on the delivery services and it was a big part of the California cannabis business model.”

The lawsuit, signed on April 4, is still in the very early stages, Finkle says. The plaintiffs have just over a month to serve the complaint, and then the responding party—in this case, the BCC—will have 30 days to respond.

The lawsuit is not the first time jurisdictions that have banned cannabis have tried to subsequently ban delivery services; an assembly bill was introduced in the state legislature this year that would have done the job, but it stalled in committee.

“They’re doing a multi-pronged attack,” Finkle says. “They tried to get new legislation, they filed a lawsuit [and] they have rules on their books where they say that delivery is banned.”

One city, Finkle adds, even went so far as to set up a sting operation.

“They were using their police officers [to] make orders to a delivery company, have the delivery company make the delivery, and then bust them,” he says.

For now, delivery services remain legal, according to the BCC’s regulations—a business in compliance with state and local regulations can deliver in jurisdictions that have banned cannabis without repercussions from the state.

“They’re not going to lose their license,” Finkle says. “They’re not going to be found out of compliance just by virtue of that delivery. So, nothing should change. It’s the status quo for now.”

However, as a result of the lawsuit, the court could issue an injunction or restraining order on the implementation of the state’s delivery rule, Annuschat says, which could disrupt the market.

“I’m not sure if the cities and counties that have made the lawsuit have requested that, but that would certainly be the next thing that would happen, if that’s going to happen,” she says. “If the restraining order is put in place, … that would obviously cause a significant delay in the implementation of this rule, and would be a significant issue for businesses that are thinking they’re going to be able to rely on this new delivery model.”

And should the cities and counties ultimately win the lawsuit, it will have an even more significant impact on the state’s cannabis industry.

“It would force delivery companies to really map out the entire state and say, ‘OK, we’re allowed to go here, but we’re not allowed to go there,’” Finkle says. “That’s crazy because there are over 500 jurisdictions in the state. I don’t know how an operator would be able to keep up with that, not to mention the rules in all these cities and counties are changing—they’re in flux constantly. It just doesn’t make commercial sense, and it really disenfranchises the consumers who voted in favor of cannabis and want to have access.”

“I would say for businesses, especially [for those] that have a delivery-only license and don’t even have a retail location, how this lawsuit plays out is going to make a significant impact on their business and probably their ability to even stay in business,” Annuschat adds.

In the meantime, Snell & Wilmer has been advising its clients to ensure that the cities they deliver in have explicitly indicated that deliveries are permitted. “If they have not said that deliveries are legal, then you should not deliver in that jurisdiction.”

Many delivery businesses may have been operating in the gray area of the law, and although they may have found relief in the state’s regulations that allow delivery services, they should not let their guard down yet. “The status quo really is that delivery may not be permitted unless they say it is legal,” Annuschat says. “But certainly, a lot of businesses have been banking on this rule getting passed, and now that this lawsuit is out there, I guess we’ll finally have a clear answer when this gets determined, whenever that may be."