Front Range Biosciences, a Colorado-based agricultural technology company, announced in March a mission to transport hemp and coffee tissue samples to the International Space Station (ISS) to see how a zero-gravity environment would impact the plants’ gene expression.

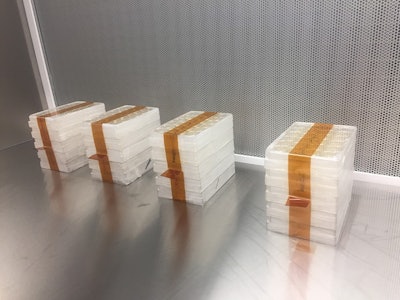

In partnership with SpaceCells USA Inc. and BioServe Space Technologies at the University of Colorado Boulder, Front Range Biosciences sent the samples aboard the March 6 SpaceX CRS-20 cargo flight to the ISS, where the tissue cultures were housed in a temperature-regulated incubator for 31 days under the care of U.S. ISS astronauts.

The environmental conditions were monitored remotely at the University of Colorado Boulder, and after the incubation period, the samples were returned to earth.

Now, the Front Range Biosciences team is regenerating and growing out the tissue cultures, examining the plants to see how microgravity and the various stressors the samples experienced have altered the cell cultures’ gene expression.

It will take anywhere from six to 24 months to produce a viable plant from the tissue cultures, according to Front Range Biosciences CEO Dr. Jon Vaught, and the team isn’t quite sure what it will discover through this project.

“This was really the first experiment on coffee and hemp plant cells like this, so it’s definitely what I would consider an early-stage research project, meaning we’re not sure what we’re going to see,” Vaught tells Cannabis Business Times and Hemp Grower. “We’re trying to cast the net wide and see what happens to the underlying biology of these plants in this format, when they go into zero gravity and the space environment, in low orbit, where the Space Station sits.”

Vaught and his team are mainly looking for changes in the plants that can be attributed to a stress response. When plants are taken from their normal environment and starved of light, water and nutrients, they undergo a stress response, which produces unique genetic markers.

In addition, Front Range Biosciences purposely altered some conditions in the plants’ space environment, such as hormone and pH levels, to assess how the plants would respond to these specific stressors in a zero-gravity environment.

“What we’re hoping is that it will give us a better understanding about how some of these genes turn on and off, which genes turn on and off, and how we might be able to use those in terms of breeding targets for our program,” Vaught says. “We’re hoping that it will inform some of the targets around things like drought tolerance … or nutrient deficiencies by understanding how the plant responded in this high-stress environment. … We can look for advantageous traits in plant varieties, which is part of our breeding program.”

Once the plants are fully regenerated, they may show signs of mutation, he adds. “It’s not a high probability, but we may see some plants that have some strange mutations that happen as a result of this experience, so we’re trying to understand what those are.”

Studying plants in space is not a new idea, Vaught says; over the past few decades, parts of the space exploration efforts in the U.S. have focused on trying to understand what happens to plants in a zero-gravity environment in the hopes that astronauts might be able to grow food while working on the ISS.

There has also been interest in the effects of microgravity on human and animal cells, he adds, where scientists have studied changes in biology to understand the impact of space travel on various organisms.

“[Gravity’s effect on plants] is that their roots grow down into the ground to search for nutrients and water, and the plant has to fight gravity to stand up and do what it does,” Vaught says. “If you put plants in that unique environment, all of a sudden, the plant doesn’t have to fight gravity anymore, so it can put its energy into other biological processes. That really drove what we’re trying to do here.”

Currently, sequencing studies on the plants are underway, and Vaught hopes to have data to report within the next few months. Then, by the end of the year, he expects that the tissue cultures will start to develop into actual plants, with visible plant-like characteristics.

“Our company is focused on figuring out how to develop and grow these plants in a wide range of environments, and the most extreme environment would be outside of the atmosphere in space, in zero gravity,” Vaught says. “As a lot of our scientists put it, it’s the most remote location we have for our field trial program, and I think it’s an exciting area of research that we want to continue to explore."