Jmîchaele Keller knows how to put a face on cannabis contaminants—his own.

The charismatic entrepreneur recently startled a room full of congressional staff by telling them about how he cut his ear in half.

Keller’s audience, gathered to learn about pesticides and other product safety concerns, cringed as he projected a photo of his grisly wound onto the U.S. Capitol Complex wall.

Although he is CEO of one of the nation’s largest cannabis testing companies—Steep Hill, with labs or affiliates in seven states—Keller lives in the Netherlands, where sales are unregulated.

When he consumed what he believed to be cannabidiol (CBD) from a tincture, he passed out almost instantaneously, waking up to find he had fallen and badly sliced his ear.

“My story is not unique. I’m sure you can find it in the U.S.,” warned Keller, who entered the industry two years ago as he embraced CBD as a treatment for a digestive condition.

It turns out there was no CBD in the tincture he used, and that isopropanol was used in the extraction process; and while isopropanol is sometimes used in home extraction (not usually in commercial extraction due to risk of residuals), residual levels remained in high enough concentrations to pose grave health risks, Keller said. The experience, Keller continued, made him see a need for federal regulation—and testing requirements for pesticides and contaminants—in the United States.

“I’m on a mission,” he said. “FDA, please help us!”

The States: Labs in the Laboratories of Democracy

With federal oversight still a distant prospect, however, states have been working to refine their own rules for pesticides.

There are still no federally approved pesticides for cannabis use, leaving states to sort through substances that cannabis cultivators are allowed to use and to define acceptable limits for those compounds.

Colorado has a list of fewer than 200 allowed pesticides and doesn’t yet require private lab testing; Washington allows 330 and requires lab testing for 13 pesticides; Oregon allows 362 and requires testing for 59.

Alaska’s Division of Environmental Health/Pesticide Control Program has a “Partial List of Pesticides that Meet Criteria to be Used on Marijuana Crops” with 145 allowed substances, and the spreadsheet noting whether each substance is a good treatment for fungus, mites, insects, slugs, worms, or for use as an insect growth regulator (IGR). Pesticide testing hasn’t yet been rolled out there.

Nevada, meanwhile, maintains a list of nearly 100 substances that can legally be used. And in California, draft rules for medical marijuana were released by the California Bureau of Marijuana Control in May, suggesting mandatory testing for 66 pesticides. Draft rules for recreational marijuana are expected later this year, and some anticipate the proposed pesticide regulations will be adopted for adult-use cannabis as well, once the medical and recreational programs are integrated under SB-94, the Medical and Adult-Use Cannabis Regulation and Safety Act (MAUCRSA).

Some medical marijuana states, such as Arizona, don’t require cannabis testing, much less specific pesticide screening. And across the country, laws are changing as regulations are debated in legislatures and among health and agriculture officials.

In states that rolled out restrictions, many labs say cultivators are increasingly falling into line.

Oregon, for example, has seen a trend toward compliance, suggests Dr. Anthony Smith, chief science officer at Signal Bay, a lab based in Oregon with a small satellite location in northern California.

“In 2015 and most of 2016 we saw failures for pesticides in flowers on the order of 15 percent of the batches we tested,” he says. “Beginning in 2017, we are slightly under 5 percent.”

In four years, Smith says the lab has only ever seen results indicating the presence of about 15 chemicals of the 59, and he feels in time he could imagine data-driven revisions to the list.

However, a white paper prepared by the Cannabis Safety Institute (CSI) in 2015 found that use of unapproved pesticides is a widespread problem, with certain substances much more common than others.

The CSI study, whose authors were based in Oregon, found 10 percent of samples contained myclobutanil—a fungicide that can create hydrogen cyanide gas when burned (relevant, obviously, to smokable forms of cannabis) and that is typically banned for cannabis use—and mite-fighting bifenazate. Imidacloprid, an insecticide, was among the most commonly detected. Smith says the top pesticides in that study retain their primacy in his lab’s results.

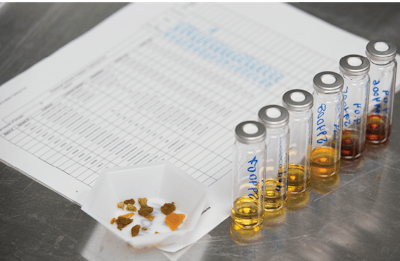

Dr. Donald Land, a University of California-Davis chemistry professor who leads Steep Hill’s pesticide-testing efforts, says pesticide use and testing protocols vary among regions. In Hawaii, for example, authorities don’t require testing for pesticides not available on the islands, he says.

States like Wisconsin, Land adds, may see less myclobutanil use, as that substance is used heavily by wine-making regions and may not be locally available.

“That’s the thing with cannabis: [Growers] use what they can get. Things that are widely available in that market,” Land says, noting that insecticidal pyrethrins derived from chrysanthemums are among the most widely detected pesticides.

Though first to roll out recreational sales, Colorado has been slow to force pesticide testing.

Luke Mason, co-owner of Colorado’s Aurum Labs, says the company bought used equipment for about $240,000 last year to test pesticides, as he was receiving inquiries about such testing. In the past year, he says, he has run fewer than 50 pesticide tests.

“I do not expect to see my money back on that until at least a year or two after testing for pesticides is required,” he says.

Dr. Claire Ohman, lab director of CMT Labs and a member of Colorado’s pesticide working group, says the group recently completed a pesticide detection-limit study, and that the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment will establish baselines “above which all of the labs should be able to detect pesticides” and that a lab-certification program for pesticides will follow in the near future.

Good Lab or Bad Lab?

Labs in different states must meet different third-party or governmental certification requirements. But should the assurances of certification give peace of mind?

Maybe not, considering controversy in Washington state, where state-accredited labs are mired in controversy about alleged cheating to attract customers, as detailed in a Leafly report this spring. In April, the Washington Cannabis Laboratory Association—a group of cannabis labs—filed a complaint with the Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board (WSLCB), alleging one of the state’s top-six labs routinely inflates THC results, with average results significantly higher than its five top competitors. In February, the Cannabis Farmers Council informed the WSLCB that a member had sent a sample to eight labs, with results from one standing well above the rest.]

In his speech at the Capitol, Keller warned of “bad scientists” and “disreputable labs.”

“There are plenty of them in every state in the country,” he said.

Land says the high cost of testing machinery may mean some labs lack the capacity to be effective. He says it takes research into the lab’s history to gather confidence, and that it’s possible for suspicious growers to send samples to different labs to verify for themselves.

Reputable labs incur additional cost to ensure their results are accurate, Smith says, noting his lab performs quality-control testing for each pesticide for every testing batch to make sure testing equipment can accurately measure a control sample.

The quality-control testing involves using an expensive, pure reference chemical of the pesticide and making sure the testing machine gives an accurate readout, he says. He encourages growers to ask labs if they’re doing it.

“Labs should be adding value to your products through good testing, not just giving you some paper that lets you enter the commercial space,” Smith says. “If you make a mistake measuring THC, people are probably not getting sick. But when you’re looking for something like a pesticide, it’s not in all samples, and if it is, it’s in very trace amounts. … You have to be able to say if the compound was there, we could have detected it.”

Organic Cultivation and Pesticides

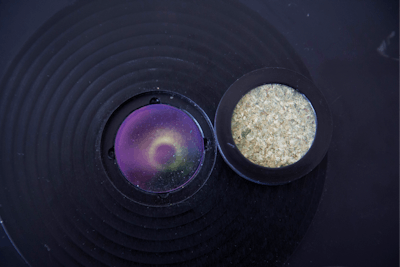

Some growers strive to grow organically, which means using natural strategies such as beneficial insects or natural oils or sprays. Trying to be organic and actually being pesticide-free, however, can be two different things.

Keller said he knew of people who “thought they were organically growing,” but testing revealed otherwise.

Land says that this might in some cases be caused by systemic pesticides in clones. (Editor’s note: See the “Systemic Pesticides” story in the May 2017 issue of Cannabis Business Times for more on this.) He says the research remains to be done, but that “the lore” among growers is that it can take five clone generations for a systemic pesticide to be totally undetectable.

Smith recalls that in Oregon, some samples tested positive for metalaxyl, initially a puzzling result as the chemical is not generally associated with cannabis. He later realized that growers with that chemical present during testing were in proximity to nearby orchards, where it is used to prevent fruit rot.

“It could be your neighbors, basically,” Smith says. “You should think about testing your soil if it’s old agricultural land or if it’s imported from somewhere.”

Taking on California

California’s large and long-unregulated market is about to meet state bureaucrats famous for big-government regulations. And it might not be pretty.

“My guess is probably 70 percent of growers use pesticides” currently in California, says cultivator and retailer Eli Bilton, specifically referring to substances that might soon be declared off-limits. The second-generation grower, who moved from the Emerald Triangle of northern California to Oregon in 2015, says, “Maybe it’s even higher.”

Land says he believes that 70 percent is a decent guess for the number of California growers currently using pesticides that the state may ban. He says Steep Hill has seen an upsurge in clients as growers prepare for mandatory testing, likely to come next year.

California is notable for the reluctance of some of its cannabis business owners to talk to reporters. A leader at one small, but well-regarded California lab declined to talk at all about pesticides for this article, saying news articles had covered the topic, and they had nothing to add.

Land says California’s transition to required testing will be messy, but that “it’s a mess everywhere.”

“The thing that’s unique to California is scale. There’s significantly more cannabis being produced,” he says. “What you have in California are microclimates up and down the state, [and] with all those different microclimates, you have different pests that are present.”

Still, for all the complexity and kinks that need to be worked out—including concentrate sampling, acceptable testing levels and batch sizes—predictions aren’t all bleak.

Land anticipates that cultivators will use far fewer unapproved pesticides once testing is required.

“Having test results will allow people to minimize the problems,” he says. “Once that happens, the good actors will come out on top.”